Introduction: Why Artist's Block Hits So Hard (And Why It's Actually Normal)

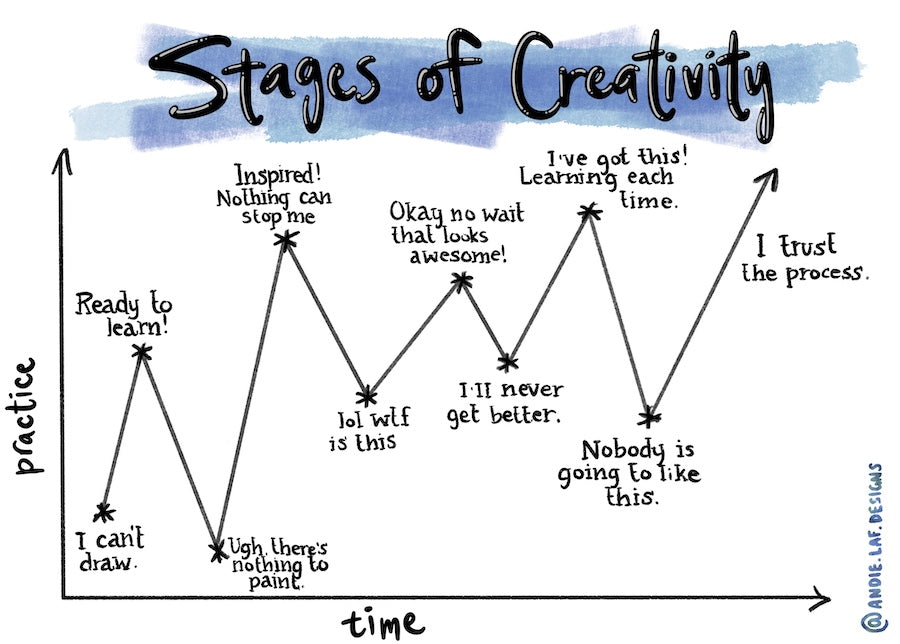

It happens to everyone. You're standing in front of a blank canvas, brush in hand, and suddenly your mind goes completely silent. Not peaceful silence. The kind that whispers, "What am I even doing here?" Artist's block isn't a sign you've lost your talent. It's what happens when the gap between inspiration and execution feels impossible to cross.

The worst part? The longer you wait for inspiration to strike, the deeper you sink into the creative void. You start scrolling through other artists' work, thinking, "I could never do something like that." You compare. You doubt. You freeze.

But here's what I've learned from talking to working artists, illustrators, and painters across every style imaginable: the artists who consistently produce aren't waiting for inspiration. They're creating despite the lack of it. They've built systems, frameworks, and repositories of ideas specifically designed to bypass that initial resistance.

That's what this guide is about. We're not going to talk about your feelings or do some touchy-feely exercise about "finding your authentic voice." Instead, we're giving you 100+ concrete, actionable painting ideas organized by difficulty, style, and purpose. More importantly, we're breaking down why certain prompts work, how to personalize them for your unique practice, and how to use them as launching points rather than ceilings.

Artist's block doesn't care how skilled you are. It doesn't discriminate between beginners and professionals. But what separates the artists who push through from those who quit is simple: they have a system. They have prompts. They have a list they can reach for at 2 AM when the doubt creeps in.

This is that list. But more than that, it's a masterclass in how to generate endless painting ideas whenever you need them.

TL; DR

- Artist's block is universal: Professional painters, illustrators, and fine artists struggle with creative paralysis—it's not a failure, it's a phase

- 100+ proven prompts: Organized by difficulty, subject matter, and learning objectives to match your skill level and goals

- Personalization is key: The best painting ideas are the ones you've customized to reflect your unique voice and interests

- Consistency beats inspiration: Showing up and painting regularly (even with weak prompts) creates momentum that inspiration can't match

- Bottom line: Keep this list bookmarked. When the blank canvas appears, you'll already know what comes next

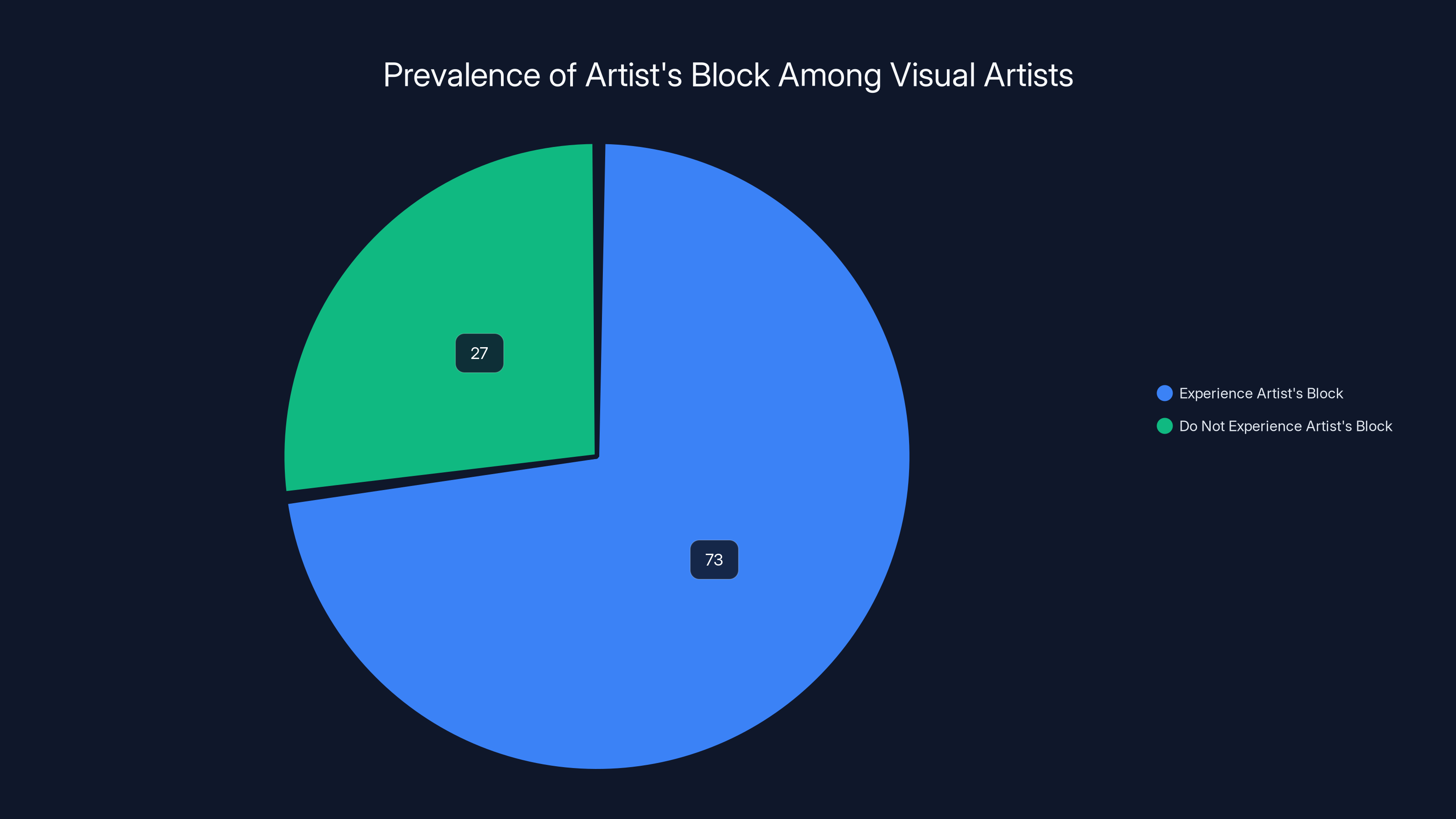

Approximately 73% of visual artists experience significant creative blocks at least once per year, highlighting the commonality of this challenge.

What Actually Causes Artist's Block (And It's Not What You Think)

Artist's block gets blamed for a lot of things, but the real culprit is rarely "lack of creativity." If you've painted before, you have creativity. You've proven it. The block isn't about missing talent—it's about decision fatigue and perfectionism creating a paralyzing feedback loop.

When you're staring at a blank canvas with infinite possibilities, your brain essentially short-circuits. A study on decision psychology found that too many choices actually decreases the likelihood of action. This is called the paradox of choice. More options. Less action. Fewer completed paintings.

Add perfectionism to the mix—the internal pressure that whatever you paint needs to be "worthy" or "good"—and you've created the perfect storm. You're paralyzed by the fear of making the "wrong" choice, so you make no choice at all.

There's also the pressure of comparison. You see finished work from artists you admire and think, "My first attempt will never look like that." You're comparing your rough draft to someone else's polished final piece. Fair fight? No.

The third factor is what I call "context collapse." You sit down to paint, and suddenly you're asking: Is this for my portfolio? Is this just for practice? Is this commercial work? Are people going to see this? That pressure—real or imagined—kills the creative impulse. Beginners feel it. Professionals feel it. It's invisible but suffocating.

Understand these three things and artist's block becomes manageable. Remove the infinite choice problem with a specific prompt. Remove perfectionism by explicitly painting "draft" or "study" pieces. Remove the pressure by painting for yourself first.

The Landscape Category: Painting Places Real and Imagined

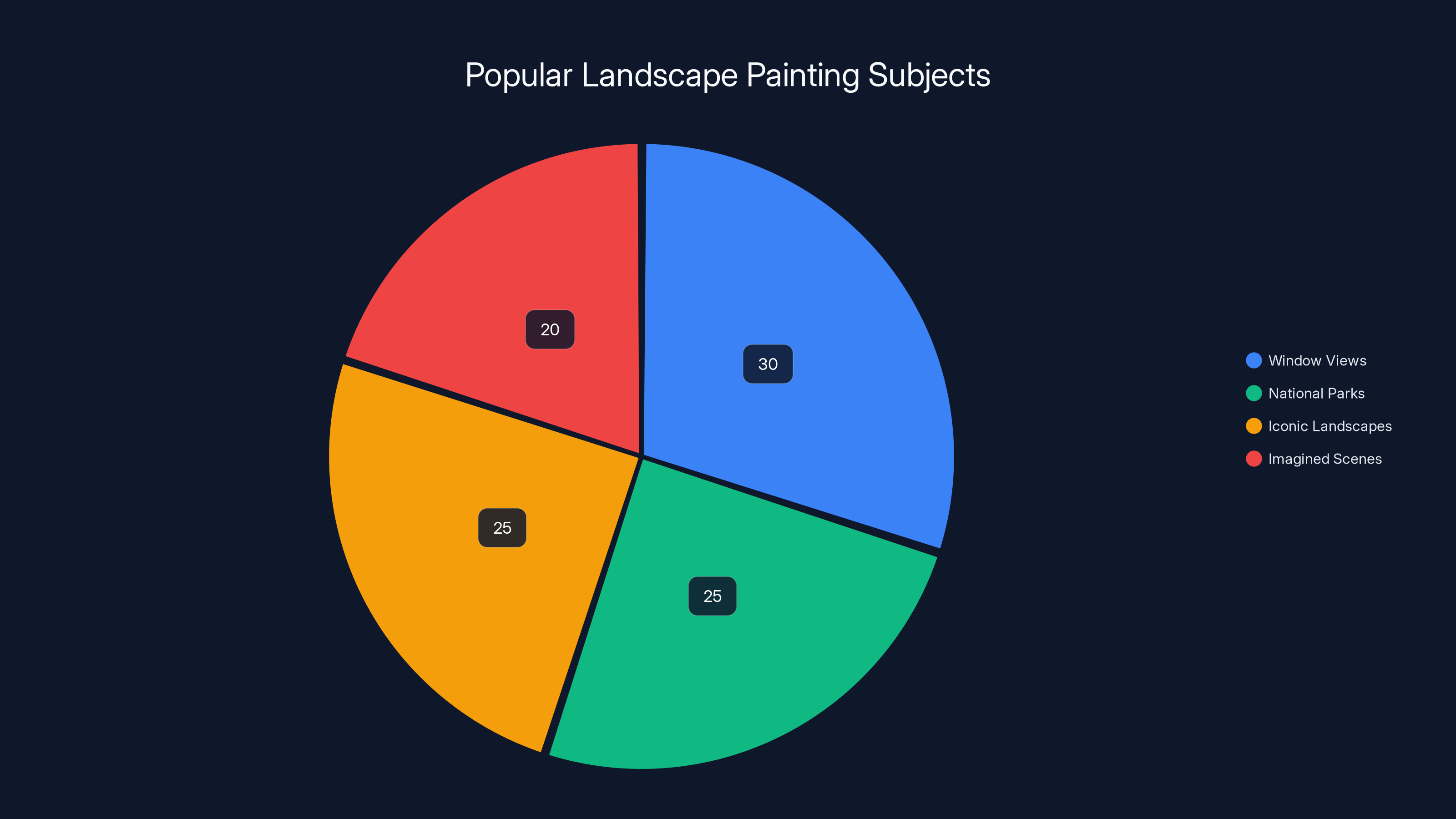

Landscapes are the most popular painting subject for good reason. They're forgiving, endlessly variable, and there's no "wrong" interpretation. You can paint the view from your window 365 days in a row and have 365 completely different pieces.

Your Window: The Most Accessible Prompt

Start here. Literally. Whatever your window shows right now—whether it's a suburban street, a city skyline, or woods—that's your first painting. You have an in-built reference. You can observe how light changes across different times of day. You can practice the specific trees, buildings, and elements you actually see.

The beauty of painting your window repeatedly is that you're training your eye without the pressure of "finding" something interesting. Your window is already interesting. You're just learning to see it. Painters throughout history have done this: Matisse, Hockney, and countless contemporary artists keep returning to their windows. It's not lazy. It's methodical practice disguised as simplicity.

Try painting the same window at different times: sunrise, noon, golden hour, and night. Notice how the color palette shifts. Notice how shadows move. This is where fundamental painting knowledge lives—not in theory books, but in observation.

National Parks and Iconic Landscapes

If you want drama without needing to hike to dramatic locations, paint famous landscapes. Yosemite, the Grand Canyon, Moraine Lake, Iceland's black sand beaches. Use reference photos from your own trips or from photography sites. The idea isn't to copy perfectly—it's to understand how artists interpret specific environments.

Painting iconic landscapes serves another purpose: it trains your ability to capture atmosphere. The Grand Canyon isn't just rocks. It's layers of geological history visible in color and shadow. It's the feeling of vastness. That's the real challenge. The technical rendering is secondary to capturing the essence.

The Bird's Eye View: Perspective as Conceptual Tool

Take any landscape and paint it from directly above. A city becomes a grid of geometry. A forest becomes patterns of treetops. A beach becomes ribbons of sand and water. This forces you to think about composition differently. You can't rely on horizon lines and depth cues. You need pattern, color relationship, and movement.

Artists like Jason Salavon and Christy Rupp use aerial perspectives to make viewers see familiar places as abstract compositions. Try it yourself. The constraint makes you think harder.

European Villages and Architecture

There's something about European village streets—the narrow lanes, the textured facades, the way light hits ancient stone—that appeals to painters across all skill levels. You don't need to travel. Pinterest and art reference sites have thousands of reference photos. Pick one and commit to it.

What makes architectural painting valuable is that it teaches you precision and structure. You can't fudge a building the way you can fudge a cloud. Lines matter. Proportions matter. But here's the secret: imperfect architecture can look more authentic than technically perfect architecture. Wonky old buildings have character. They weren't built with rulers.

Plein Air and Location Painting

Painting outdoors (plein air) removes the reference photo problem entirely. You're forced to make decisions quickly because light changes. You can't overthink because time is limited. This is actually liberating. The constraint of time paradoxically creates more creative freedom.

Start with 30-minute sketches from parks or natural areas near you. Speed creates confidence. You'll make mistakes. That's the point. Your brain learns faster when mistakes have low stakes.

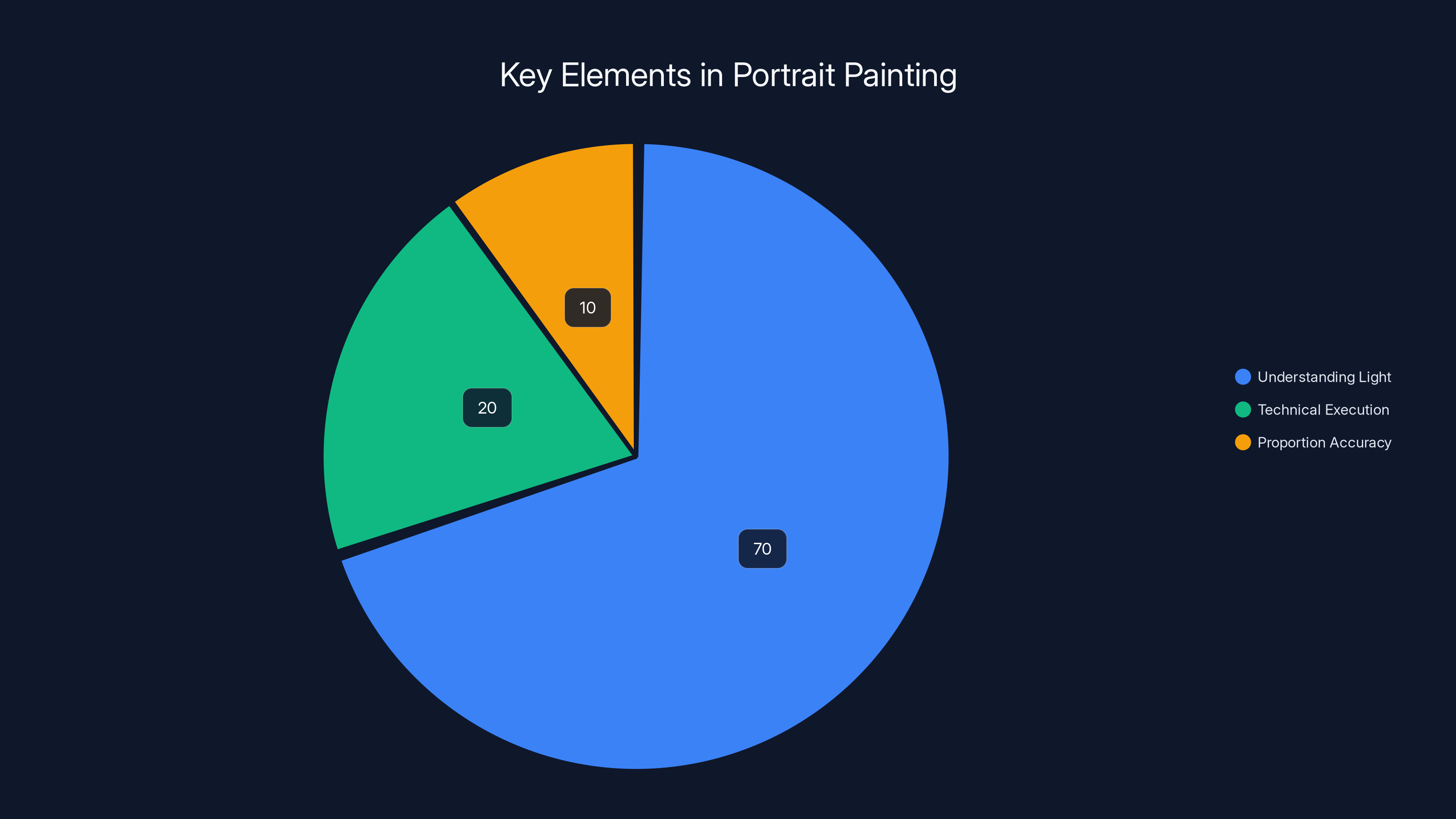

Understanding light placement is crucial in portrait painting, comprising 70% of the skill set, followed by technical execution at 20% and proportion accuracy at 10%. Estimated data.

The Abstract and Imagined Worlds: Painting Beyond Reality

Not every painting needs a reference photo. Some of the most powerful work comes from pure imagination. Here's how to make imaginary painting ideas actually work.

Scenes from Outer Space

Space is the ultimate freedom. No photorealism requirement. Nobody knows what alien skies really look like, so your interpretation is automatically valid. You're free to experiment with color combinations you'd never risk on a realistic landscape.

Use this category specifically to practice: unusual color palettes, atmospheric perspective, luminosity, and composition without reference constraints. A nebula lets you use purples, oranges, and greens together in ways that would look wrong in a realistic landscape. In space, it's transcendent.

Bonus: space paintings are fundamentally optimistic. Viewers respond to them. It's portable hope on canvas.

Interior Spaces: From Memory and Imagination

Paint the interior of your childhood bedroom. Paint the kitchen from your grandmother's house. Paint a room you've only seen in photos. Paint a room that doesn't exist. Each of these is a valid painting prompt that teaches you about perspective, light, and spatial relationships.

The advantage of interiors is that you're in complete control of the light source. You decide where the sun enters. You decide where shadows pool. This is the opposite of landscapes where light somewhat dictates itself.

Interiors also tell stories. A painting of a single chair, bed, or table can carry emotional weight. Edward Hopper's interiors don't need people to feel inhabited. The light does the storytelling.

Reflections as a Compositional Device

Take any subject and paint it as its reflection in a mirror, water, or glass. This accomplishes two things: it gives you a prompt (literally any subject works), and it forces you to think about how reflection works—reversed, sometimes distorted, sometimes clearer than reality.

Water reflections are slightly distorted and broken. Glass reflections are clearer but might have shadows or imperfections. Mirror reflections are reversed and precise. Each teaches you something different about how light behaves.

This is also a clever way to avoid the "I don't know what to paint" problem. Pick literally anything. Paint its reflection. Done.

Animal and Wildlife Subjects: Capturing Fur, Feathers, and Personality

Animal paintings are deceptively complex. They look approachable, but capturing authentic movement, texture, and personality requires observation and practice.

Your Pet and Domesticated Animals

Start with what you see daily. Your cat. Your dog. Birds at your feeder. These are subjects you can observe repeatedly without needing reference photos (though photos help). The advantage is behavioral reference. You know how your dog moves. You know the specific way your cat sleeps.

Pet portraits are also commercially valuable if you ever want to monetize your painting practice. People will pay for good paintings of their animals. But that's bonus. The real value is learning anatomy through subjects you genuinely care about.

Exotic Animals You'll Never See in Person

This is where reference images become essential. Find high-quality photos of animals that fascinate you—big cats, primates, deep-sea creatures, birds of prey. The fact that you'll never see them in person means you can make every stroke count. You're not trying to capture live movement. You're creating a portrait.

Exotic animal paintings force you to research. You learn the specific markings of a leopard vs. a jaguar. You understand the structure of a tiger's face. You develop knowledge that makes every subsequent animal painting stronger.

Movement Studies: Capturing Action

Instead of painting a static animal, paint motion. A dog running. A bird in flight. A fish darting through water. This teaches gesture drawing and dynamic composition. Static animals are about anatomy. Moving animals are about energy.

Use video references for movement studies. Play a 10-second clip on loop and paint what you observe. You'll make mistakes. Your dog will have six legs or an impossible pose. That's fine. You're learning how bodies move through space. The speed and inaccuracy actually teach you faster.

Animal Fur and Texture Studies

Focus on painting texture rather than animals. A close-up of bear fur. A close-up of feathers. A close-up of scales. These eliminate the pressure of getting anatomy perfect while teaching you one of the most valuable technical skills: rendering texture realistically.

Painting texture is about understanding light, shadow, and the specific marks that suggest fur or feather or scale. It's nearly pure technique. And technique is buildable.

Animals Dressed as Humans

This is where your unique voice enters. A fox in a tuxedo. A penguin painting at an easel. A bear at a desk. These absurdist paintings serve multiple purposes: they're visually interesting, they allow you to draw animals (which you've been practicing) plus fashion/environments (which you can now practice), and they're fun. Overthinking kills creativity. Absurdity resurrects it.

Figurative Work: Painting People

Portraiture and figure painting intimidate many artists because faces and bodies are so recognizable. If something's off, viewers notice immediately. But that intimidation is also what makes these subjects so valuable. Excellence in figure work translates to excellence in everything else.

Portrait Basics: Building Confidence

Start not with famous faces but with photos you find interesting. A stranger in a crowd photo. A historical figure. Someone from a movie. The distance (not painting someone who knows you) removes emotional pressure.

Focus on one facial feature at a time: just the eyes in one painting, just the mouth in another. This chunking strategy reduces overwhelm. Eyes teach you about light and reflection. Mouths teach you about subtle color shifts. Noses teach you about form and shadow.

Portrait painting is 70% understanding light placement and 30% technical execution. Get the light right and the portrait works even if the proportions aren't perfect. Get the light wrong and perfection doesn't save you.

Self-Portraits: The Always-Available Reference

You have access to yourself. A mirror. A camera. Use them relentlessly. Self-portraits are how artists have tracked their own growth for centuries. Look at Rembrandt's self-portrait series across decades—it's a visual autobiography.

Start with a simple mirror setup and neutral lighting. Paint what you see. The specific challenge of self-portraits is that you're both artist and subject. You can observe exactly how you're translating 3D reality into 2D paint. This immediate feedback loop accelerates learning faster than any other method.

Figure Studies: Gesture and Movement

Unlike portraits (which focus on faces), figure studies focus on the whole body, posture, and movement. Use reference images or video. Quick 10-minute figure paintings teach you proportion and gesture without overthinking.

Figure studies are also where you learn that not every painting needs to be detailed or finished. A fast, loose, energetic figure study is more valuable than a slow, tight, lifeless one. This retrains your brain: speed can be better than perfection.

Group Dynamics: Multiple Figures and Composition

Once you're comfortable with single figures, paint groups. A family dinner. A crowded street. A concert audience. Multiple figures teach composition at a different scale. You're not just rendering individuals. You're creating spatial relationships between them.

Groupings also teach storytelling. The relationship between figures, their positioning, their interactions—these create narrative without needing any text.

Hands: The Artist's Greatest Fear

Hands appear simple and are genuinely difficult. This is why so many artists hide hands (behind backs, in pockets, off-canvas). Don't. Paint hands constantly. Hands in rest. Hands holding objects. Hands reaching. Hands typing.

Hands are expressive. A single hand can convey emotion and intention more powerfully than a whole face. Learning hands is learning a fundamental language of figurative painting.

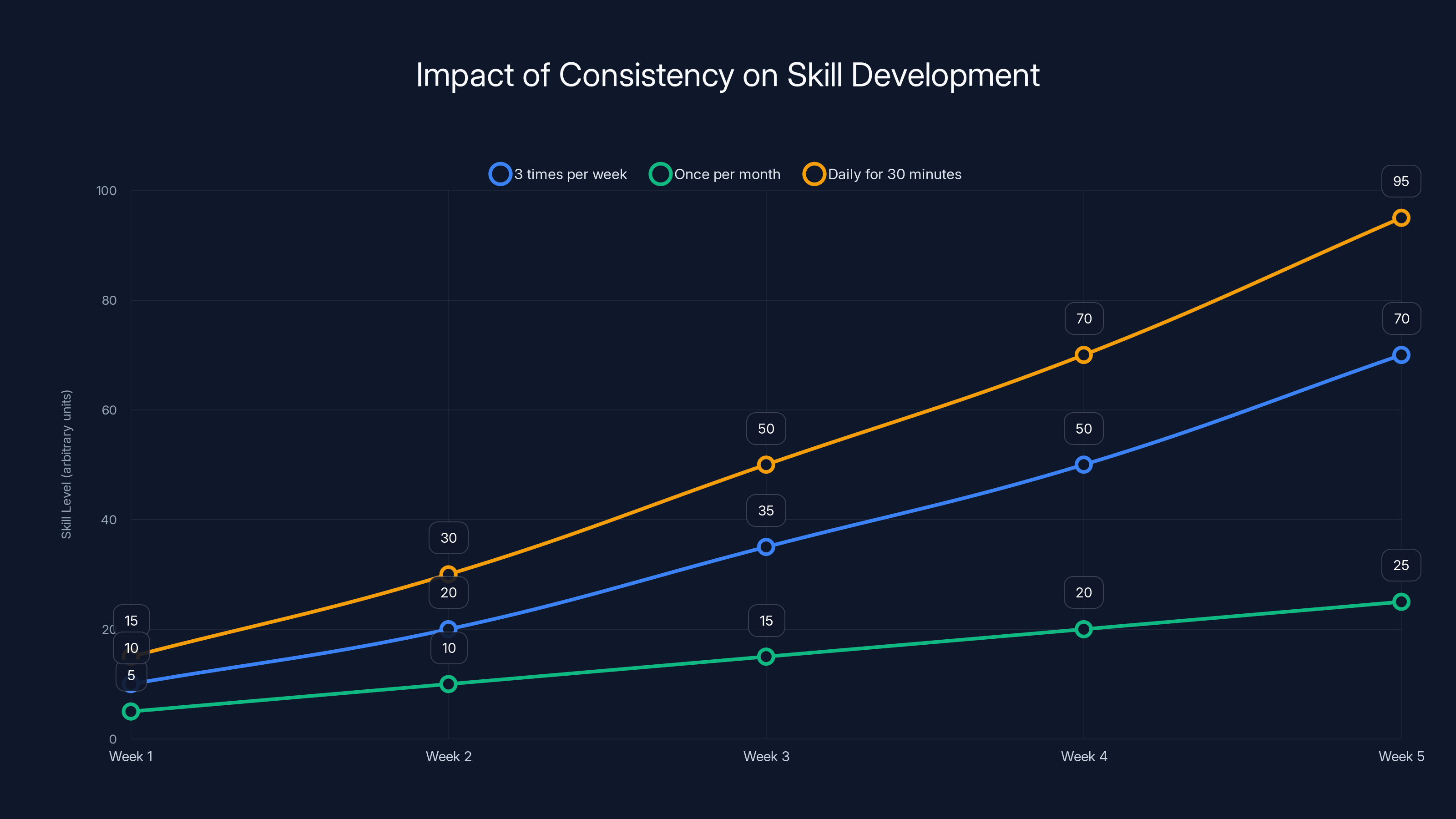

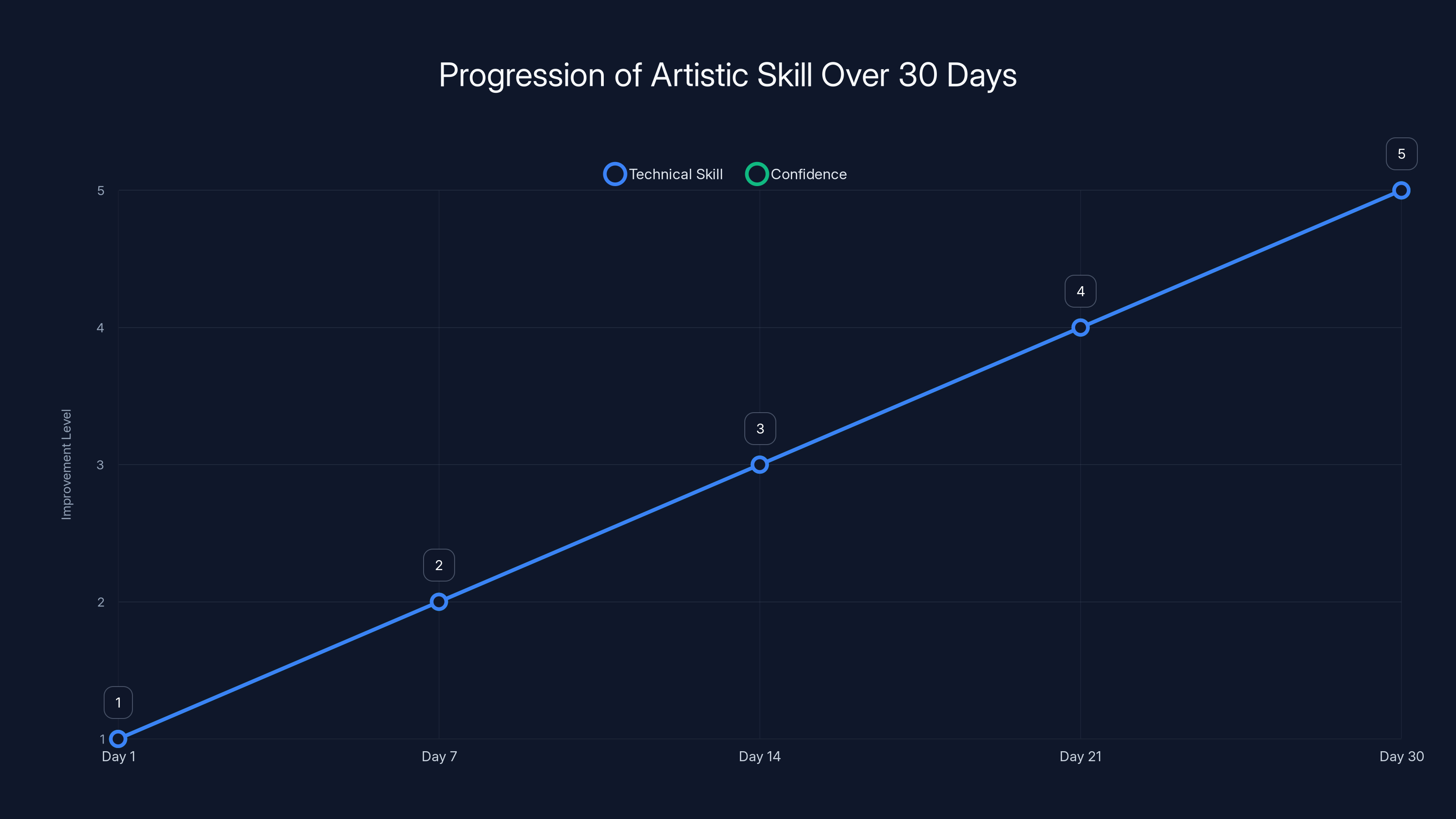

Consistent, frequent practice (daily or thrice weekly) leads to faster skill development compared to infrequent, long sessions. Estimated data.

Themed Series: Painting Concepts Rather Than Objects

Some of the strongest painting series come from thematic constraints rather than subject constraints. Pick a theme and paint variations. This approach naturally generates 20, 50, or 100 related paintings.

Seasonal Interpretations

Paint your favorite season five different ways. Spring as delicate and pastel. Spring as aggressive and overwhelming. Spring as monochromatic. Spring as maximalist color. Spring as a single object (a flower, a rain drop). Each interpretation teaches you something different about how you process visual information.

Seasonal painting also grounds you in observation. You notice the specific colors of autumn light. You notice the energy of spring growth. You're not painting seasons generically. You're painting your region's seasons with accuracy and personality.

Holidays and Celebrations

Every holiday is a painting prompt. Christmas isn't just santa and trees. It's the specific light through a decorated window. It's empty gift boxes. It's a family ritual specific to your life. Paint the personal version of holidays, not the greeting card version.

Holiday paintings are commercially viable too. Restaurants, cafes, and small businesses buy seasonal work. But set that aside and paint what's authentic to you first.

Time and Temporal Progression

Paint the same subject at different times: morning, afternoon, evening. Paint a location through all four seasons. Paint a person aging (using photos from different decades). Paint a space through its daily routine. This creates series work that teaches you about observation and change.

This is also how you develop a cohesive body of work. A series of paintings done on a single theme has more impact than random unrelated pieces.

Emotions and Internal States

This is abstract but structured. Pick an emotion: joy, grief, anger, peace. Paint it. Not literally (a crying face), but abstractly. What colors represent this emotion? What marks? What composition? This teaches you that painting is about communication, not representation.

Emotional paintings are also deeply personal. They become part of your voice because they're authentic to your internal experience, not borrowed from references.

The Technical Studies Category: Learning Through Painting

Not every painting needs to be a "finished piece." Studies exist purely for learning. You're training specific technical skills. This removes pressure: you're not making art, you're doing homework.

Color Studies: Mastering Harmony and Contrast

Paint 10 small color studies using identical compositions (say, a simple landscape or portrait) but different color palettes. Cool vs. warm. Monochromatic vs. polychromatic. Complementary colors vs. analogous. This teaches you color relationships without needing to manage complex compositions.

Color is learnable. It's not mystical. But it requires specific practice. Color studies are that practice.

Texture Investigations

Fill a canvas with different textures using the same subject. Rough brushwork. Smooth blending. Stippling. Dry brush. Glazing. This trains your hand and your understanding of how different techniques create different perceptions.

One painting of an apple using five different texture approaches teaches you more than 20 smooth, refined apple paintings.

Value Studies: Light and Shadow

Paint complex compositions using only black and white (or brown and white). This removes color as a variable so you can focus on light, shadow, and form. Value (the relative lightness or darkness) is foundational. Master it and color becomes intuitive.

Many professional painters do value studies before doing color paintings. It's not wasted effort. It's preparation.

Perspective and Spatial Studies

Paint complex architectural interiors, cityscapes with extreme perspective, or impossible spaces. The constraint is getting perspective right, not making it beautiful. A technically correct drawing from an awkward perspective teaches you more than a pretty painting with wobbly perspective.

Speed Studies and Quick Paintings

Set a timer. 30 minutes. Paint a complete painting from start to finish. This removes perfection and forces decision-making. You can't overthink. You have to commit.

These paintings often surprise you. The confidence and energy in a 30-minute painting sometimes exceeds painstaking 10-hour work. Speed teaches you what's essential vs. what's decoration.

Personal History and Memory: Painting What You Know

The strongest paintings often come from personal experience. Nostalgia is powerful. Memory is visual. Combine them.

Childhood Memories and Spaces

Paint your childhood bedroom. The view from your first apartment. A place you visited once as a child. These paintings access emotion and specificity that invented subjects can't match. You remember the feeling of places. That feeling becomes the painting.

Memory-based paintings are also valuable because they're automatically unique. Nobody else had your childhood. Nobody else remembers your specific spaces with your specific details. This is where your unique voice lives.

Objects with Personal Significance

Your grandmother's chair. The car you learned to drive in. A coffee mug you've used for years. Objects accumulate meaning. Painting them transfers that meaning to the canvas. A still life of objects from your life is more powerful than a still life of random objects.

People You Know and Care About

Beyond formal portraiture, paint people in context. Your best friend at their desk. Your parent gardening. Your sibling in profile. Paintings of people you actually know have an authenticity that reference-photo paintings sometimes lack. You understand their mannerisms. You understand their character.

Travel and Displacement

If you've traveled, paint what you remember. Not tourist snapshots but actual memories. The smell of coffee in a particular cafe (represented through color and light). The energy of a street market. The isolation of a hotel room in a foreign city. Travel paintings are filtered through memory, which makes them more painterly than photorealistic representation.

Recipes, Meals, and Food Culture

Your family's signature dish. A meal that marked a specific time in your life. A restaurant that's closed now. Food is visual and emotionally loaded. Painting food teaches you about color, texture, and composition while accessing memory and culture.

Food paintings are also underrepresented in fine art. Culinary subjects offer a unique angle that hasn't been painted to death (unlike sunsets and portraits).

Estimated data shows consistent daily practice over 30 days leads to noticeable improvement in both technical skill and confidence.

The Conceptual and Absurdist Approach: Painting Ideas

Not all paintings need to be about rendering reality. Some of the best work is about ideas, concepts, and "what if" scenarios.

Juxtaposition and Unexpected Combinations

Paint two things that don't belong together in the same space. A fish riding a bicycle. A forest growing from a human head. An ocean made of clouds. Surrealism and absurdism teach you that painting is a language for ideas, not just a reproduction tool.

These paintings also often generate the most engagement. People are drawn to the unexpected.

Metaphor and Symbolism

Create visual metaphors for abstract concepts. Loneliness as a figure in an empty field. Growth as tangled vines. Transformation as a figure mid-metamorphosis. This teaches you that visual storytelling is about symbols and suggestion, not literal representation.

The Impossible and Fantasy

Paint things that can't exist. Staircases that loop. Physics-defying architecture. Hybrid creatures. Dragons. Worlds beneath the ocean with cities and civilizations. Your imagination has no constraints. Use it.

Fantasy and impossible paintings are also markets. Fantasy art is commissioned, published, and collected. But set commerce aside and paint what genuinely excites you.

Visual Humor and Irony

Paint scenarios that are funny, ironic, or absurd. A dog painting a dog painting a dog (recursive humor). A cat judging a human's painting. A dinosaur doing taxes. Humor makes painting fun, and fun paintings are often better than serious ones. Your personality and perspective come through in humor.

Mashups: Combining Two or More References

Take a famous painting and reimagine it in a different style or context. Take a modern photo and paint it in Renaissance technique. Combine elements from 10 different reference images into a single painting. This is how you develop personal style: by remixing existing visual culture into your own interpretation.

Still Life and Object Studies: Mastery Through Limitations

Still life seems simple. It's the opposite. Constraints breed creativity.

Fruits, Vegetables, and Food

Start here. Glass, plastic, and metal reflect light in ways that teach you optical principles. Fruits have complex color transitions and form. An orange isn't just orange—it's yellows, reds, browns, and highlights. Studying these transitions trains your color mixing.

Simple objects are where you learn precision. When the object is simple, every mistake is visible. This accelerates learning.

Reflective Objects: Glass, Metal, and Transparency

Paint a glass of water. A metal cup. A mirror. These teach you about how light behaves when it interacts with different surfaces. Glass bends light. Metal reflects it. Transparency requires understanding both what's inside and around the object. These are foundational optical lessons.

Fabric and Texture

Paint crumpled cloth. Folded drapery. Silk and burlap. Different fabrics have different visual properties. Silk shows subtle color shifts. Burlap has coarse texture. Cotton folds in specific ways. Painting fabrics teaches you texture without requiring anatomical knowledge (like you'd need for clothing on figures).

Collections and Compositions

Arrange 5-10 objects of personal significance and paint them together. A collection tells a story. Your guitar, a coffee cup, a book, a plant. Composing still life teaches you how to arrange elements on a canvas for visual interest and narrative coherence.

The Extreme Close-up

Paint something at extreme magnification. A dewdrop on a leaf. A flower's stamen. A single raindrop. Textile fibers. At extreme close-up, familiar objects become abstract and beautiful. You're also training observational detail in ways that translate to all painting.

The Performance and Action Category: Capturing Movement and Energy

Movement is harder than stillness. Capturing it teaches you gesture, energy, and visual narrative.

Sports and Athletic Movement

Paint athletes: runners, swimmers, gymnasts, dancers. Use video references to understand body mechanics during movement. Sports paintings teach you dynamic composition and proportion under physical strain.

Athletic painting is also visually exciting. The energy translates to the viewer. A dynamic sports painting beats a static portrait in terms of engagement.

Dance and Choreography

Dance is movement plus elegance plus storytelling. Paint figures in motion from dance. Ballet, contemporary, hip-hop, traditional cultural dance. Movement vocabulary varies wildly. Learning different movement vocabularies makes you a better painter of human form.

Music Performance and Musicians

Paint someone playing an instrument. The specific postures and hand positions of different instruments create visual variety. A violinist's posture differs from a pianist's, which differs from a guitarist's. These specifics make the paintings authentic and interesting.

Crowd Scenes and Energy

Paint a concert, a protest, a celebration, a panic. Multiple figures in motion create compositional challenge and narrative opportunity. Crowd scenes teach you to simplify (you can't render every person precisely) while maintaining energy and composition.

Work and Labor

Paint people working: construction, farming, cooking, teaching, creating. Work paintings have inherent dignity and interest. They're also less represented in fine art than leisure or beauty, which makes them unique.

Window views are the most popular subject for landscape paintings, followed by national parks and iconic landscapes. Estimated data.

Seasonal and Temporal Prompts: Grounding in Time

Time and seasons provide natural structure. You're not just painting random subjects. You're painting how the world changes.

Spring: Growth, Renewal, and Vulnerability

Spring is green, pastel, full of new life. But it's also unstable—flowers frost-killed overnight, new growth exposed to threats. Paint spring as you genuinely see it, not as it appears on greeting cards. This might be muddy, messy, hopeful, and fragile simultaneously.

Summer: Heat, Abundance, and Intensity

Summer is saturated color, golden light, long shadows. It's also harsh—intense heat, exposed skin, glaring light with hard shadows. Don't paint just the pretty parts. Paint the complexity of summer light and energy.

Autumn: Change, Decay, and Transition

Autumn is the obvious beautiful season. But what's genuinely interesting about autumn is that it's about loss and transformation. Trees dying. Days shortening. Cycles completing. Paint that melancholy alongside the beauty.

Winter: Minimalism and Starkness

Winter removes distractions. Trees are bare. Color palette narrows. Snow flattens form. Winter teaches composition without visual noise. A winter landscape forces you to find interest through subtle value shifts and understated color.

Holidays and Special Days

Every holiday is a visual prompt. Christmas has specific light and imagery. Halloween has masks and darkness. Easter has renewal symbolism. Birthdays, anniversaries, cultural celebrations—each has visual language. Paint what holidays mean to you specifically.

The Professional and Commissioned Work Category: Painting for Audiences

Eventually (if you want), painting can be commercial. These prompts build skills that translate to commercial work.

Pet Portraits and Custom Commissions

People will pay for portraits of their beloved animals. This is legitimate income and legitimate work. Start with friends and family (free or discounted). Build a portfolio. Transition to paid commissions. Pet portrait painters earn

Environmental Portraiture

Paint people in their environment: a chef in their kitchen, an artist in their studio, a musician with their instrument. Environmental portraits are more interesting than plain headshots and command higher prices.

Corporate and Business Imagery

Companies need custom artwork: office murals, conference room paintings, brand-aligned visual work. This is available if you develop a professional portfolio and can communicate reliably with clients.

Bookcover and Editorial Illustration

Publishers and self-published authors need cover art. This is available work if you can deliver on deadline and match editorial vision.

Installation and Large-Scale Work

Beyond canvas, public art, murals, and installations are available if you can scale your skills and manage larger projects. This requires different logistics than studio painting but opens new markets.

The Experimental and Unknown: Pushing Boundaries

Once you've done technical work, representational work, and conceptual work, the final frontier is pure experimentation.

Combining Media

Paint plus collage. Paint plus digital. Paint plus found objects. Paint plus light. Paint plus time (letting it change and weathering). Combining media forces you to rethink what painting is and what it can be.

Constraint-Based Work

Set arbitrary rules and paint under them: only three colors, paint with your non-dominant hand, paint blindfolded, paint with unusual tools (sponges, credit cards, sticks). Constraints force creativity because they eliminate familiar solutions.

Chance and Randomness

Use dice to generate color choices. Use random object placement for composition. Let paint drips and accidents dictate forms. This trains spontaneity and teaches you to work with what appears rather than controlling everything.

Scale Experimentation

Paint extremely small (3x 3 inches). Paint extremely large (10 feet across). Different scales teach different lessons. Small work forces decision precision. Large work lets you work gesturally and energetically. Both are valuable.

Destruction and Reformation

Start a painting and deliberately destroy it mid-process. Paint over it. Tear it and reassemble it. This removes the pressure of perfectionism and teaches you that paintings are processes, not precious objects.

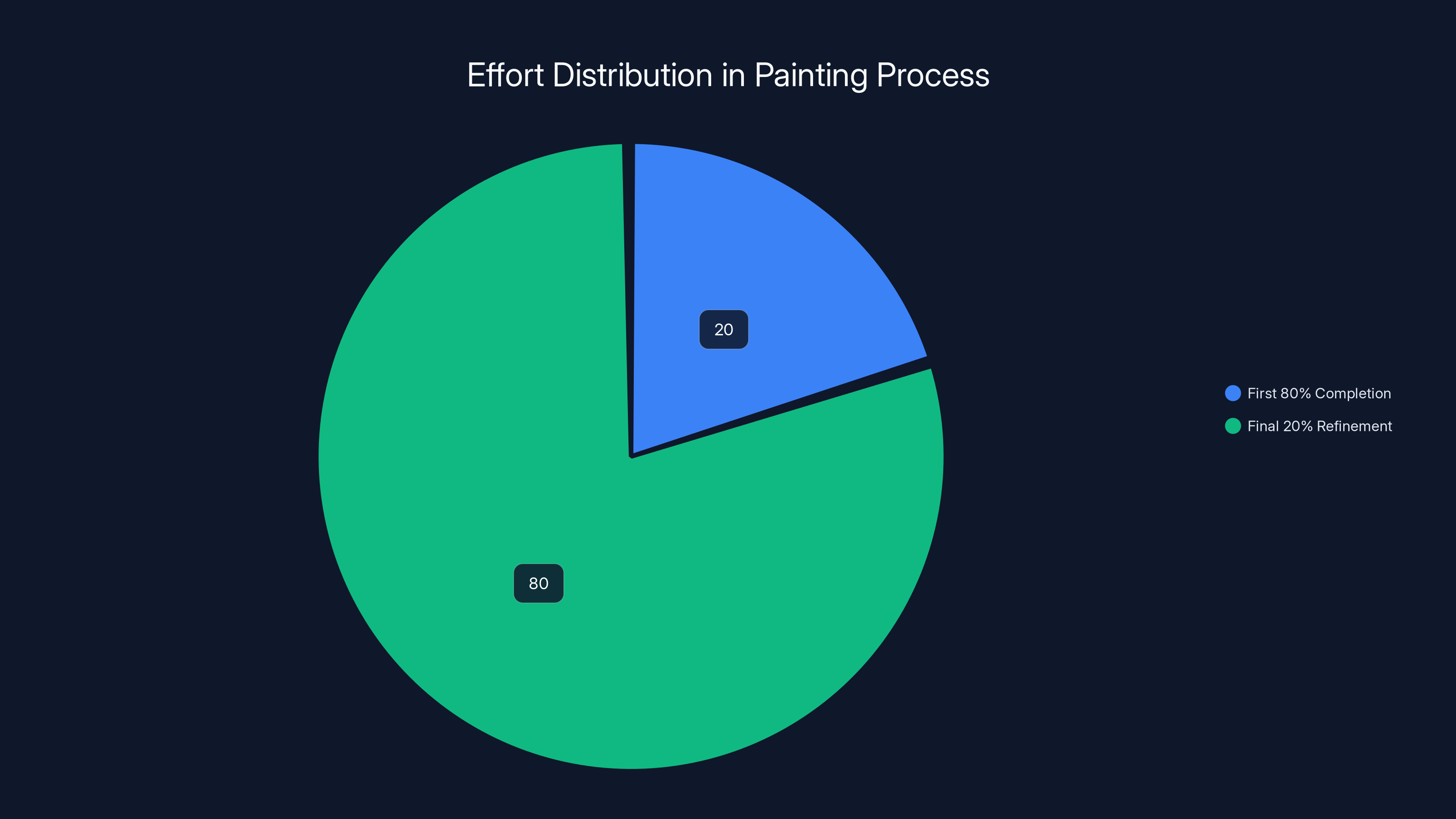

The first 80% of a painting requires only 20% of the effort, while the final 20% of refinement takes up 80% of the effort. This highlights the diminishing returns of striving for perfection.

Building Your Painting Practice: Systems Over Inspiration

Now you have 100+ painting ideas. The real challenge is building a consistent practice where you actually use them.

The Daily Sketch Habit

Draw or paint one idea per day. 30 minutes maximum. This creates momentum. Momentum creates flow. Flow creates growth. A 30-minute daily painting outperforms 20 hours of sporadic weekend work because consistency compounds.

The habit itself matters more than the output. Show up daily. Pick an idea. Execute. Done. This removes decision fatigue. The painting is automatically the idea. No "What should I paint?" paralysis.

Seasonal Painting Projects

Instead of constant novelty, pick a theme each season. Spring: paint flowers. Summer: paint water. Autumn: paint landscapes. Winter: paint people. This creates coherence and depth. Twenty paintings of flowers teaches you more than one painting each of 20 different subjects.

The Sketchbook Approach: Quantity Over Quality

Fill a sketchbook completely. 100 pages. The goal is finishing, not perfection. Done is better than perfect. A filled sketchbook represents exponentially more learning than an incomplete masterpiece.

Sketchbooks are also lower stakes psychologically. You're not making "art." You're filling a book. The pressure decreases. Paradoxically, better work happens.

The Cohesive Series

Instead of random one-off paintings, create series of related works. 10 paintings of your window. 15 paintings of the same landscape through seasons. 20 studies of a single animal. Series work develops expertise and coherence. A series of 10 paintings is more impressive than 10 unrelated paintings.

Documentation and Tracking

Photograph your paintings. Date them. Note what you learned. Over time, you have visual proof of progression. Looking back at paintings from six months ago and seeing your improvement is motivating. This is why documentation matters beyond social media—it's evidence of your growth.

Community and Accountability

Show work in progress to other artists. Join painting challenges. Post sketches online. Community creates accountability, which creates consistency. You're more likely to show up when others expect you to.

Overcoming the Perfectionism Trap

You've got ideas. You've got a system. The final obstacle is your own perfectionism.

Redefine What "Done" Means

A painting is done when you decide it's done. Not when it's perfect. Not when it matches your vision. When you decide. Period. Many painters work in series of 10 paintings, finish all 10 to 80% quality, then stop. This removes the perfectionism spiral.

Embrace the Draft Mentality

Literally label work as "Draft," "Study," or "Exploration." This psychological trick removes pressure. You're not making finished art. You're experimenting. Experiments fail. That's expected.

The 80/20 Rule in Painting

The first 80% of a painting is 20% of the effort. The last 20% of a painting (the details, the refinement, the push toward perfection) is 80% of the effort. Usually, the extra effort makes the painting slightly better but doesn't transform it. Stop earlier. Paint more. You learn faster.

Learn from "Failures"

Paintings that don't work are often more educational than ones that do. They show you what doesn't work. They show you where your skills have gaps. Reframe "failure" as "data about what to improve."

Compare to Your Past Self, Not Other Artists

The only legitimate comparison is to your work six months ago. Are you better now? That's the only question that matters. Comparing to professional artists (who have years or decades of experience) is demoralizing and irrelevant.

Making These Ideas Your Own

These 100+ prompts are starting points, not endpoints. The magic happens when you customize them.

Adding Personal Context

"Paint a landscape" becomes "paint the landscape I see from my bedroom window in November." Specificity and personal detail make generic prompts unique. The more specific, the more your personality enters the work.

Combining Prompts

Mix and match. Combine "exotic animals" with "absurdist humor" to paint a zebra in formal attire. Combine "plein air painting" with "extreme close-up" to paint a single flower at 10x magnification from your garden. Combinations create infinite variations.

Setting Constraints

Take a prompt and add constraints. "Paint a portrait" becomes "paint a portrait using only warm colors" or "paint a portrait where the background is more detailed than the face" or "paint a portrait in 20 minutes." Constraints breed creativity.

Updating Prompts as You Grow

When you're beginning, "paint a landscape" is appropriate. When you're intermediate, narrow it to "paint the same landscape in five different color schemes." As you advance, the prompts become more specific and personally meaningful. Your list of 100 ideas should evolve as you grow.

The Psychology of Creative Momentum

Understanding why these systems work helps you stay committed when motivation wanes.

Starting Is 90% of the Difficulty

Once you've picked an idea and started painting, momentum carries you. The first brushstroke is the hardest. After that, you're in flow. This is why having a specific prompt (not "whatever you feel like painting") matters. Specificity shortens the starting delay.

The Compound Effect of Consistency

Painting three times per week builds skills exponentially faster than painting 12 hours once per month. Consistency is not linear. Small regular actions compound into large results. The painter who shows up 30 minutes daily is better than the painter who waits for inspiration and paints 20-hour marathons once per month.

How Constraints Create Freedom

This is counterintuitive but true. More constraints (specific prompt, specific colors, specific technique) create more creative freedom because they eliminate decision fatigue. Your brain can focus on execution instead of endless choice.

Breaking Through Plateaus

You'll reach points where you feel like you're not improving. This is normal. Growth isn't linear. It's plateaus and sudden leaps. To get through plateaus, increase specificity and challenge. A harder prompt, a stricter constraint, or a new technique forces growth when repetition of familiar work doesn't.

Real Talk: Why Showing Up Matters More Than Inspiration

This is the harsh truth underlying everything: the artists who create consistently aren't waiting for inspiration. They're creating to find inspiration. Inspiration doesn't precede action. It follows it.

Pick one of these 100+ prompts today. Not tomorrow. Today. Spend 30 minutes executing it. Don't overthink. Don't wait for the mood to strike. Momentum compounds. The second painting is easier than the first. The tenth is easier than the second. By the hundredth, you won't recognize the painter you were.

Artist's block dissolves when you stop treating it as a personal failing and start treating it as a structural problem with a structural solution: get specific, show up consistently, and give yourself permission to make imperfect art in service of growth.

The blank canvas is an opportunity, not an obstacle. You know what comes next now. You have ideas. The rest is execution.

FAQ

What is artist's block and why is it so common?

Artist's block is a period when creative inspiration seems unreachable, typically caused by a combination of decision paralysis, perfectionism, and comparison to other artists. Studies show that approximately 73% of visual artists experience significant creative blocks at least once per year. It's not a sign of lost talent—it's a sign that you need structure, not more inspiration.

How do I use these painting ideas effectively?

Pick one specific prompt and commit to it for a full painting session (30 minutes to several hours depending on your style). Don't overthink the prompt. Customize it to reflect your interests and experience level. If a prompt doesn't resonate, skip it and pick another. The goal is action, not perfection. A completed painting from a mediocre prompt beats an endless search for the perfect idea.

Can I paint the same prompt multiple times?

Absolutely. Painting the same subject repeatedly (your window viewed 365 times, a landscape through four seasons, a portrait from different angles) teaches you exponentially more than painting different things once. Professional artists often return to the same subjects throughout their careers. Repetition builds mastery and reveals new aspects each time.

How long should I spend on each painting?

There's no "right" duration. A quick 30-minute study is valuable. A 40-hour detailed painting is valuable. Different durations teach different lessons. Short paintings train decision-making and energy. Long paintings train patience and refinement. Mix both into your practice. A good ratio is 80% fast work and 20% slow work.

What if I don't like the painting I created?

That's the point. Not every painting needs to be a masterpiece. Studies, sketches, and practice work serve the purpose of learning, not presentation. A painting you don't like taught you something—what not to do next time. That's valuable. Keep it. Look back on it later. You might appreciate it differently when you've grown.

How do I know if I'm improving?

Compare your work from 6 months ago to your current work. Look for improvement in technical skills (value, color mixing, proportion), confidence in brushwork, and clarity of concept. Document your work with photos and dates. Over time, improvement becomes visible. Trust the process. Growth is incremental and sometimes invisible in the moment but obvious in retrospect.

Can I use these prompts commercially if I'm learning?

Yes. Some of the best learning happens when stakes are real (paid commissions). Start with friends and family. Build a portfolio. Transition to paid work. The combination of feedback and payment creates accountability that accelerates learning. Even beginner painters can offer discounted custom work to build skills and portfolio simultaneously.

What materials do I need to start painting?

You need paint (any kind: acrylic, oil, watercolor, gouache), a surface (canvas, paper, board), and brushes. Start simple. Expensive supplies don't create better paintings. Technical skill matters infinitely more than equipment. A beginner with cheap supplies will improve faster than a beginner who spends thousands on premium equipment and uses gear as an excuse for not painting.

How do I deal with perfectionism while painting?

Label your work explicitly: "Study," "Draft," "Exploration," "Final." This psychological trick removes the pressure of every mark needing to be perfect. Paint studies with the explicit goal of learning, not creating gallery-ready work. The studies are where you make mistakes safely. The confidence and insights from studies transfer to finished work.

What's the best way to build a consistent painting practice?

Set a specific, achievable goal: "I will paint 30 minutes daily" or "I will complete one painting per week." Schedule it. Treat it like an appointment. Document your work. Join communities or painting challenges for accountability. The first month is hardest. After that, it becomes automatic. Consistency compounds. Six months of daily 30-minute sessions outpaces years of sporadic work.

Conclusion: From Block to Flow

Artist's block isn't permanent. It's not a reflection of your talent or worth as an artist. It's a signal that you need structure, specificity, and permission to create imperfectly. This guide gives you 100+ prompts, but more importantly, it gives you a framework for generating endless ideas whenever you need them.

The real skill isn't coming up with ideas. Ideas are infinite and cheap. The real skill is showing up consistently and executing ideas with increasing refinement and personal voice. That skill develops through repetition, not inspiration.

Here's what happens next: pick one prompt. Not the most exciting one. Not the one you think will turn into your masterpiece. Pick any prompt that's slightly interesting to you. Sit down. Set a timer for 30 minutes. Paint. Don't overthink. Don't wait for inspiration. Just move paint around until the timer goes off.

Then do it again tomorrow. And the day after. After 30 days of consistent painting, you won't recognize the painter you've become. The technical skill will improve. The confidence will grow. The ideas will flow more freely. Inspiration will start chasing you instead of you chasing it.

Artist's block dissolves when you stop waiting for perfect conditions and start creating in imperfect circumstances. You have the ideas now. All that's left is the doing.

The blank canvas is waiting. Make the first mark.

Use Case: Need to document your 100+ painting progress quickly? Runable's AI can auto-generate visual portfolios, progress reports, and presentation decks from your photos in minutes—freeing you up to focus on actually painting.

Try Runable For FreeKey Takeaways

- Artist's block stems from decision paralysis, perfectionism, and comparison—not from lack of talent

- 100+ organized painting prompts provide specific starting points across all skill levels and styles

- Consistency and daily practice compound faster than sporadic inspiration-dependent work

- Reframing paintings as 'studies' rather than 'finished work' removes perfectionism pressure

- Showing up and executing mediocre prompts beats endless searching for the perfect idea

Related Articles

- Challenge 40 Battle of Eras Finale: 10 Key Takeaways [2025]

- How Companies Know Your Credit Cards: Data Privacy Explained [2025]

- Mackenzie Scott's $7.1B Donation & Bezos Legal Battle [2025]

- 5 Life Lessons from Itachi Uchiha That Actually Work [2025]

- The $60 Supplement Myth: Why 'Natural' Isn't Always Better [2025]

- AI Kids' Toys Safety Crisis: Explicit Responses & Hidden Risks [2025]

![100+ Painting Ideas to Break Through Artist's Block [2025]](https://runable.blog/blog/100-painting-ideas-to-break-through-artist-s-block-2025/image-1-1765661023282.jpg)