The $60 Supplement Myth: Why 'Natural' Isn't Always Better

You've seen them on your Instagram feed. Sleek bottles with earthy aesthetics. Celebrity testimonials. Before-and-after photos. The promise: take these pills and you'll finally feel like your best self—energized, youthful, balanced. The price tag? Sixty dollars for a month's supply. The company? Something with a name that sounds vaguely ancestral, like they're selling you a secret your grandmother's grandmother knew.

The supplement industry has figured out something powerful: women are frustrated. Frustrated with healthcare systems that dismissed their concerns for decades. Frustrated with feeling tired, hormonal, and invisible in waiting rooms. Frustrated with not getting answers.

And that's where companies like Primal Queen step in.

They're not selling vitamins. They're selling a story—one that promises you can optimize your biology by eating like your ancestors did. One that suggests modern food has failed you, but their proprietary blend of organ meats in capsule form will fix everything. Nearly 200,000 Instagram followers. Viral on Tik Tok. Third-party tested. All the signals that scream credibility.

But here's what actually matters: Do these supplements work? Are they worth $2 per day? And most importantly, what's really going on in the marketing playbook that convinced so many people they need them?

This is where science, consumer psychology, and a healthy dose of skepticism come in.

TL; DR

- Appeal to nature fallacy: The core marketing strategy assumes "natural" automatically means safe and effective—but arsenic is natural too

- Nutritional reality check: Most Americans aren't deficient in the nutrients these supplements claim to provide (B12, zinc, iron, vitamin A)

- Regulatory gray zone: Supplements operate under minimal FDA oversight compared to pharmaceuticals, meaning claims don't need rigorous proof

- Marketing over evidence: Month-by-month "timelines" and vague benefits like "vitality" are designed to feel personalized while remaining impossible to verify

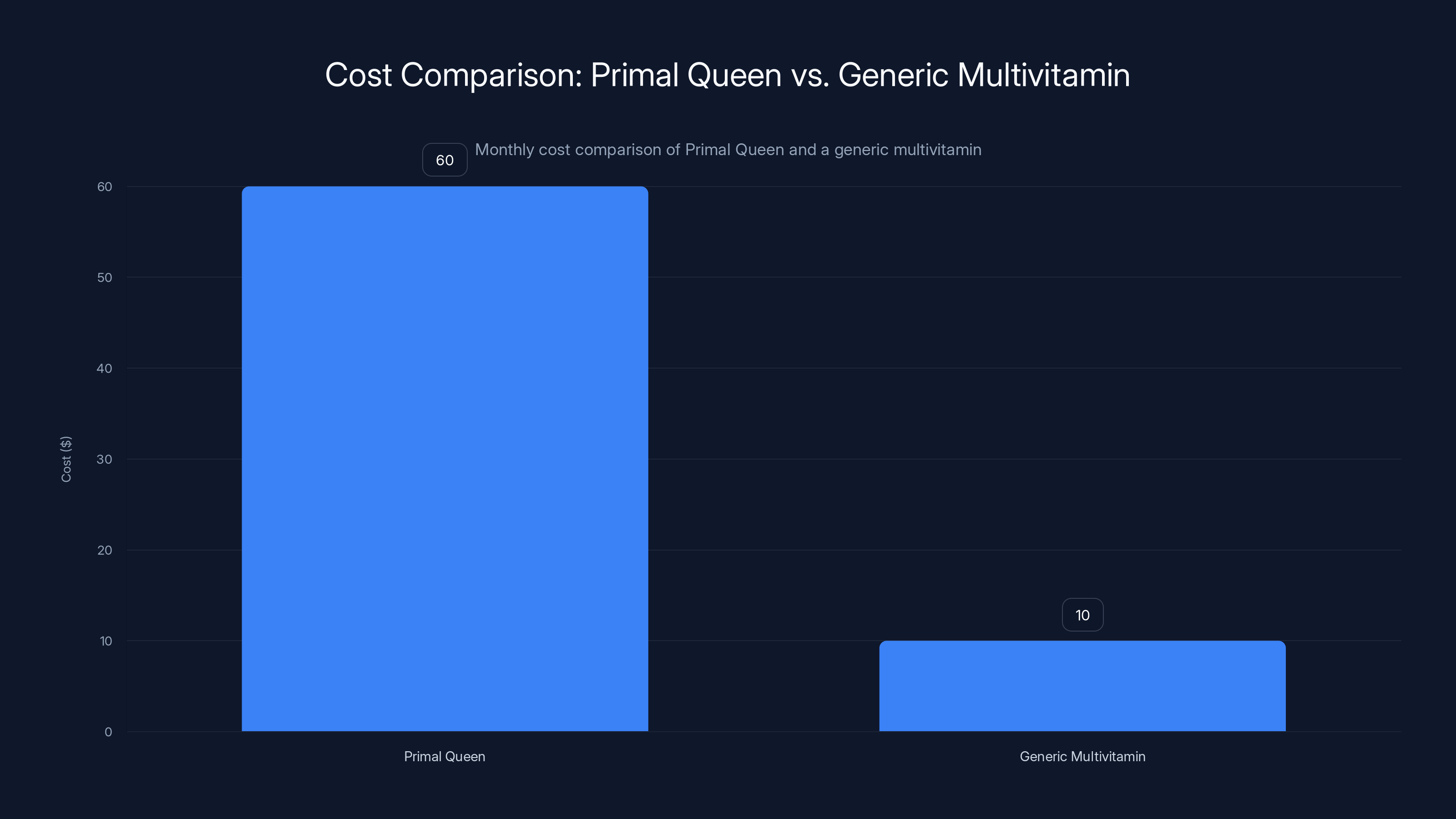

- Cost-benefit analysis: A $60 monthly supplement costs 1,500x more than addressing actual deficiencies through food or basic multivitamins

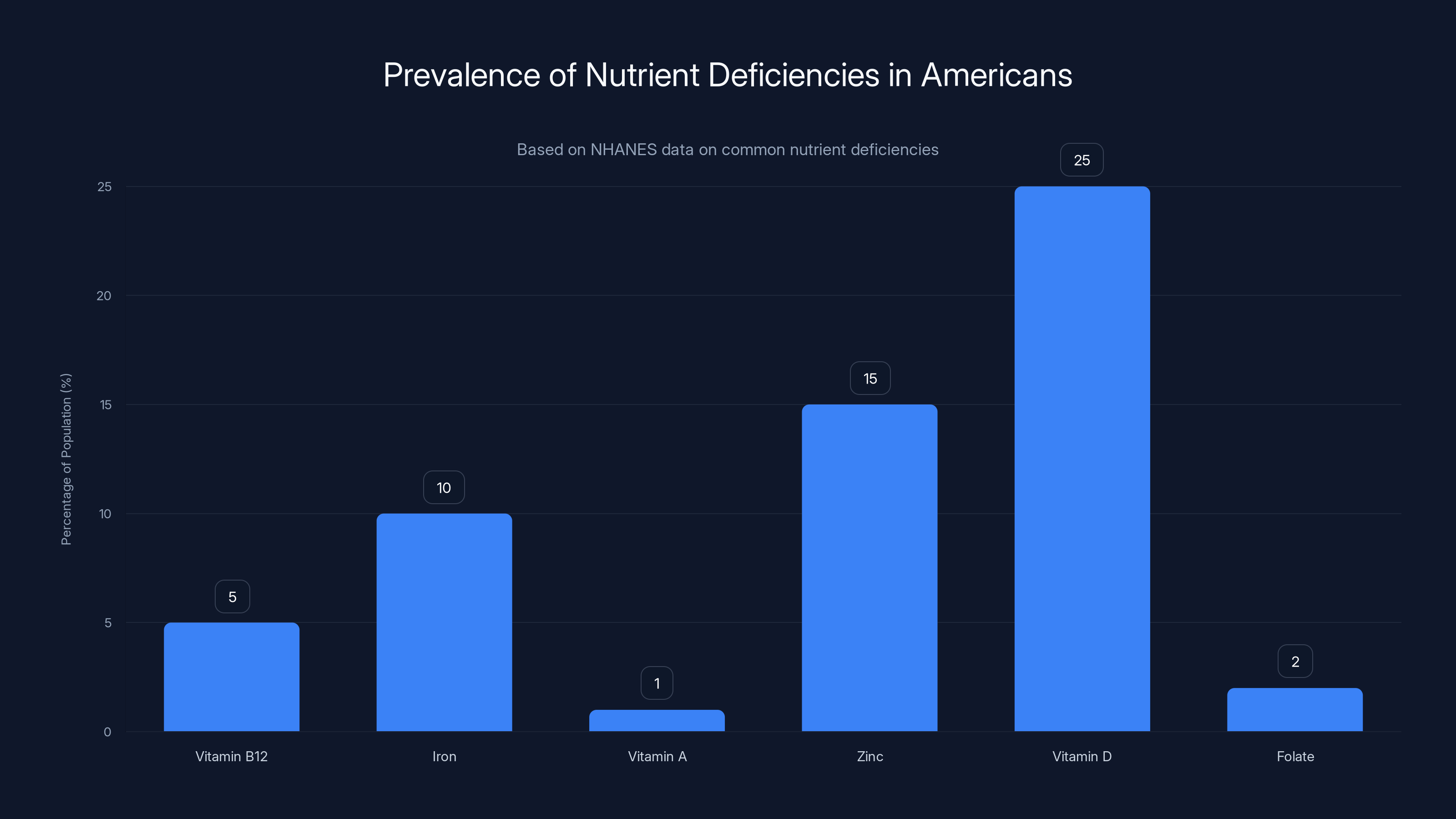

Vitamin D deficiency is the most prevalent among Americans, affecting about 25% of the population, while Vitamin A and Folate deficiencies are rare. Estimated data based on NHANES findings.

Understanding the Appeal to Nature Fallacy

What It Is and Why Our Brains Fall for It

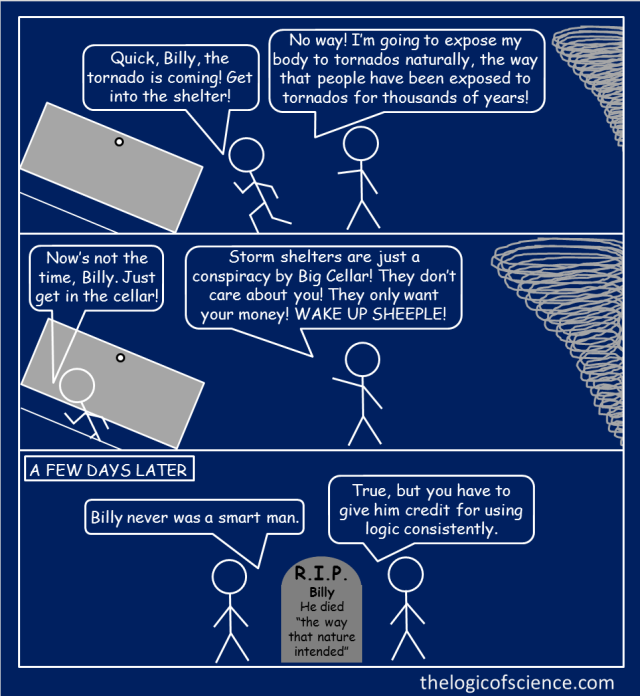

The appeal to nature fallacy is a cognitive bias that sounds deceptively simple: if something is natural, it must be better, safer, or more effective than its synthetic counterpart. It's not new. This bias has been baked into human psychology for millennia—our ancestors didn't have access to poison labs or synthetic toxins, so "natural" usually meant "safe to eat." That heuristic served them well.

But it completely falls apart in the modern world.

Consider the facts: ricin is natural. So is hemlock. Cyanide occurs naturally in apple seeds. Lead, mercury, and arsenic? All natural elements found in the earth. Conversely, penicillin is synthetic, chemically designed in a lab—and it's saved millions of lives. Insulin is made by bacteria in fermentation tanks, not extracted from a pristine natural source. These synthetic compounds are rigorously tested, standardized, and proven safe in ways that many "natural" products simply aren't.

Yet when you see a bottle labeled "all-natural," something in your brain lights up. It feels safer. It feels like you're choosing the option your grandmother would have chosen. It feels honest in a way that a white pill from a pharmaceutical company doesn't.

Primal Queen's entire marketing strategy hinges on exploiting this exact cognitive bias. Their packaging screams "primal." Their copy emphasizes that these nutrients come "straight from natural sources rather than lab-made." Their timeline shows you exactly what month you'll notice results, creating what researchers call a "illusion of control"—you're not just passively hoping supplements work; you're actively tracking your progress toward optimization.

The Ancestral Diet Argument (And Why It's Oversimplified)

The company's core narrative is simple: modern women should eat like "carnivorous cavewomen" to optimize their health. This ancient-wisdom angle is powerful. It suggests that somewhere back in time, humans figured out the perfect diet—and we've since deviated from it, making ourselves sick.

The problem? The archaeological evidence doesn't support it.

Isotope analysis of pre-agricultural human remains from sites in Morocco indicates that early humans were highly reliant on plant foods, not primarily carnivorous. They foraged for diverse vegetation—seeds, nuts, tubers, fruits, leaves—and occasionally hunted when they could. Their diet varied enormously based on geography, season, and availability. A human living in a coastal region ate vastly differently from one in grasslands or forests.

More importantly, early humans didn't live longer because they had access to better nutrition. They had much shorter lifespans, high infant mortality, and frequent malnutrition. They also lacked antibiotics, modern medicine, and clean water—the things that actually extended human lifespan over the past century.

Yet Primal Queen's marketing invokes this ancestral imagery while selling you something your ancestors could never have conceived of: factory-processed supplements in gelatin capsules, manufactured in industrial facilities, distributed globally through e-commerce.

It's a paradox. The brand appeals to primitivism while being entirely dependent on modern technology and industrial food systems. You can't forage for bovine uterine powder. You can't hunt gelatin capsules.

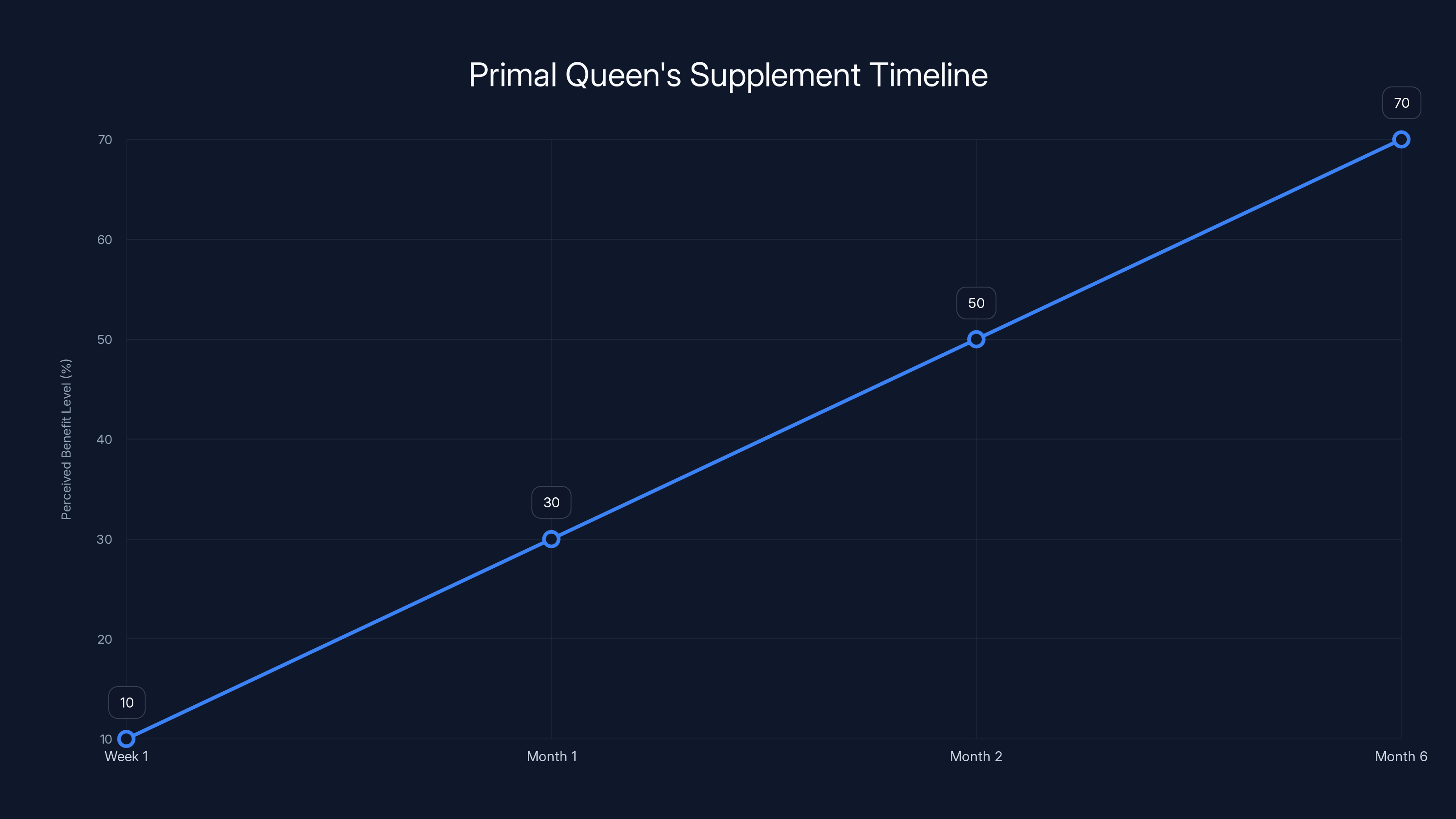

The timeline suggests a gradual increase in perceived benefits, with significant milestones at each stage. Estimated data based on product claims.

The Marketing Timeline: Month-by-Month Magic

How Vague Claims Sound Personalized

On Primal Queen's website, you'll find something deceptively clever: a detailed month-by-month timeline showing exactly when you should experience benefits. Week 1: energy and mood. Month 1: sex drive and vitality. Month 2: immunity and stress reduction. Month 6: mental clarity and muscle recovery.

This isn't just product information. It's a psychological tactic.

The timeline serves multiple purposes simultaneously. First, it makes the supplement feel personalized to your journey. You're not just taking a pill and hoping—you're following a protocol. You're tracking progress. There's a sense of structure and intentionality. Second, it creates what's called a "self-fulfilling prophecy." If you believe you should feel more energized in week one, you'll unconsciously notice small energy fluctuations and interpret them as the supplement working. You'll credit your morning coffee to the pill instead. You'll sleep slightly better one night and assume the formula is kicking in.

Third—and this is crucial—the timeline uses vague language that sounds scientific but resists measurement. "Vitality," "well-being," "enhanced mental clarity," "improved recovery." These aren't clinical outcomes. You can't measure them objectively. They can't be disproven. If you feel even marginally better after a week, you'll interpret the timeline as accurate.

Deconstructing Specific Claims

Week 1: "Energy, mood, and cognition due to Vitamin B12, zinc, and copper"

Let's look at the actual science. First, B12 deficiency is rare in most Americans—it primarily affects strict vegans who don't take supplements, people with pernicious anemia, or those with certain gastrointestinal conditions. The average American gets plenty of B12 from meat, dairy, and fortified cereals. Taking more B12 beyond your deficiency level won't give you more energy. It's water-soluble, meaning excess is excreted in urine. You can't overdose, but you also can't "boost" your energy beyond baseline unless you were previously deficient.

Zinc deficiency affects roughly 15% of Americans and is more common in certain populations. But again, most people get adequate zinc from meat, legumes, seeds, and nuts. If you're not deficient, taking zinc won't make you smarter or happier. In fact, excess zinc supplementation can interfere with copper absorption, creating new problems.

Copper deficiency is genuinely rare in the US. Very rare. Taking copper supplements when you're not deficient can be counterproductive.

Month 1: "Increased vitality and sex drive due to iron"

Here's where it gets interesting. The third-party testing Primal Queen references shows 0.0013% iron in their supplement sample. But here's the critical issue: there's no iron amount listed on the actual packaging. This means customers have no way to verify how much iron they're actually consuming. And there's only one batch tested—not ongoing quality control across manufacturing batches.

More fundamentally, abnormal uterine bleeding can cause both iron deficiency and sexual dysfunction in women. But any suspected iron deficiency should be diagnosed through blood work and treated under medical supervision. You shouldn't be guessing about your iron status based on a symptom checklist. Women who have iron deficiency anemia need real treatment from a healthcare provider, not a $60 supplement gamble.

Month 2: "Better mood and healthy immune system from B vitamins"

B vitamins are water-soluble. Your body doesn't store them. You need to consume adequate amounts daily. But "adequate" doesn't mean "more is better." B vitamins are available in common foods: meat, fish, dairy, leafy greens, legumes, whole grains. If you eat a reasonably varied diet, you're getting B vitamins. Adding a supplement doesn't compound the effect. It's like pouring more water into a cup that's already full.

Month 3: "Better skin, delayed aging, and improved vision from vitamin A"

Less than 1% of Americans are at risk for vitamin A deficiency. Let that sink in. Less than 1%. The claim about vitamin A preventing aging targets cosmetic concerns, not actual health needs. And while vitamin A does support vision, this benefit only applies to people who are deficient. If you're not deficient—which most Americans aren't—more vitamin A doesn't give you better vision.

Here's the deeper issue: vitamin A is fat-soluble, meaning excess amounts are stored in your liver and can accumulate. Too much vitamin A can actually be toxic, causing joint pain, bone loss, and liver damage. This is why "more is better" thinking is genuinely dangerous with fat-soluble vitamins.

Month 6: "Enhanced mental clarity and better muscle recovery"

Why six months? Why does the timeline show benefits "peaking" at exactly six months? There's no physiological reason for this arbitrary endpoint. The vagueness is intentional. By month six, you've invested $360 in supplements. You've been primed by the timeline to expect results. You've attributed your normal daily mood fluctuations and occasional good sleep nights to the supplement. The timeline has done its psychological work.

The Regulatory Gray Zone: How Supplements Avoid Scrutiny

Why "Dietary Supplements" Aren't Pharmaceuticals

Here's something most supplement consumers don't understand: supplements operate under a completely different regulatory framework than drugs. This isn't a small technicality—it fundamentally changes what companies can claim and what testing they're required to do.

When a company wants to bring a new pharmaceutical to market, the FDA requires rigorous testing. Phase I, II, and III clinical trials. Thousands of patients. Placebo controls. Months or years of safety monitoring. The company must prove efficacy. The burden of proof is on the manufacturer. If the drug doesn't meet the standard, it doesn't get approved.

Supplements? Different story entirely.

Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), passed in 1994, supplements are presumed safe until proven otherwise. The burden of proof is on the FDA to prove something is unsafe—not on the manufacturer to prove it works. Companies can make "structure-function claims" (claiming the supplement affects normal structure or function of the body) without FDA approval, as long as they include a disclaimer that the statement hasn't been evaluated by the FDA.

This creates an enormous loophole. Primal Queen can claim their supplement increases "energy," "mood," and "sex drive" without conducting a single clinical trial. They don't need to prove these claims work. They just need to include a tiny disclaimer that the FDA hasn't evaluated them. The regulatory framework essentially says: "You can sell this, make these claims, and as long as it's not actively poisoning people, we're not going to stop you."

Third-Party Testing: What It Actually Means

Primal Queen advertises third-party testing through Eurofins laboratory. This sounds impressive. Independent verification. Rigorous standards. Credibility.

But here's what third-party testing actually checks: Does this product contain what the label says it contains? Is it contaminated with heavy metals or pathogens? That's valuable information. You do want to know your supplement isn't contaminated.

But third-party testing doesn't test efficacy. It doesn't verify that the supplement actually does what the company claims. It doesn't compare this supplement to placebo. It doesn't follow patients over time. It's a quality assurance test, not a clinical validation test. Eurofins is checking chemistry, not health outcomes.

Yet marketing puts "third-party tested" in large letters on the packaging, creating an impression of scientific rigor that the testing doesn't actually provide. It's credibility by association—linking the supplement to legitimate laboratory work while obscuring what that work actually measures.

The "Structure-Function" Claim Loophole

Primal Queen makes claims like "better mood," "improved sex drive," "enhanced mental clarity." These are structure-function claims—they suggest the supplement affects normal body functions without claiming to treat disease. This is the crucial legal distinction that lets them make these claims without FDA approval.

Compare that to a pharmaceutical company claiming a drug improves depression or sexual dysfunction. That company faces FDA enforcement. They need clinical evidence. They need to list side effects and contraindications.

But "mood" and "well-being"? Vague enough that companies can claim them without proof.

Primal Queen costs

The Nutritional Reality: What Americans Actually Need

Are We Really Deficient?

The marketing premise behind Primal Queen and similar supplements is that modern food has left us nutritionally depleted. That our soil is depleted. That our food lacks the nutrients our ancestors had. That we need supplements to fill the gap.

Let's check this against actual data.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) tracks nutritional status in Americans. The data shows:

- Vitamin B12 deficiency: Less common than you'd think. Affects primarily vegans and people with certain digestive conditions

- Iron deficiency: Primarily affects women with heavy periods and infants. Most adult males and post-menopausal women have adequate iron

- Vitamin A deficiency: Affects less than 1% of Americans

- Zinc deficiency: Affects roughly 15-20% of certain populations, but is relatively rare in the general population who eats animal products

- Vitamin D deficiency: This is legitimate. Many Americans, particularly in northern climates and people with darker skin in lower-sun regions, have inadequate vitamin D

- Folate deficiency: Rare since food fortification began

So what's actually missing from the modern American diet? The short answer: usually nothing except potentially vitamin D, and sometimes iron in specific populations.

Yet the supplement industry has built a massive business on the premise that everyone is deficient in everything. Primal Queen suggests that adding their formula will boost energy, mood, sex drive, mental clarity, muscle recovery, and vision. That's a lot of claims from one supplement targeting people who usually aren't deficient in those nutrients.

The Bioavailability Question

Primal Queen claims their nutrients are superior because they come from "natural sources rather than lab-made." The implication is that your body absorbs and uses them better.

This touches on something real—bioavailability, or how much of a nutrient your body actually absorbs and can use. But the natural vs. synthetic distinction doesn't actually determine bioavailability. It depends on the specific nutrient and how it's formulated.

Vitamin C is vitamin C whether it comes from an orange or a lab. Your body processes it identically. Iron is iron. Zinc is zinc. The molecular structure is the same.

Where bioavailability matters is in how nutrients are combined, their chemical form, and your personal digestive health. Some formulations are more easily absorbed than others. But this has nothing to do with whether they're natural or synthetic. A synthetic nutrient can have better bioavailability than a natural one, depending on how it's formulated.

Moreover, consuming excessive amounts of a nutrient doesn't improve bioavailability. If your body needs 10mg of zinc and you consume 50mg, you don't absorb and use all 50mg. You absorb what you need and excrete the excess. Paying a premium for "natural" sources doesn't change this fundamental physiology.

Cost Comparison: What You're Actually Paying For

Let's do the math.

Primal Queen:

Basic multivitamin:

Difference:

What are you paying for with that premium? The appeal to nature. The marketing. The timeline. The Instagram aesthetic. The feeling that you're doing something sophisticated and ancestral.

What evidence supports paying 50-150x more for Primal Queen versus a basic multivitamin? Essentially none. Both provide micronutrients. Both are unlikely to address any actual deficiency in a person eating a reasonably varied diet.

If you have a suspected deficiency, the right move is blood work, not guessing. If you're deficient in something specific, you should be buying that specific nutrient—iron, vitamin D, B12—not a proprietary blend that claims to do everything.

When Supplements Actually Make Sense

The Legitimate Use Cases

This isn't an argument against all supplements. Some people actually need them.

Vegans and vegetarians genuinely benefit from B12 supplementation. B12 is primarily found in animal products, and B12 deficiency in vegans is real and documented. A cheap B12 supplement is medically appropriate here—not a luxury product, but a necessity.

Pregnant and breastfeeding women need additional folate and iron, per medical guidelines. A prenatal vitamin isn't an optional wellness product; it's part of standard prenatal care. The evidence for prenatal supplementation is strong.

Vitamin D supplementation is evidence-based for people in northern climates, people with limited sun exposure, people with darker skin in low-sun regions, and people with conditions affecting fat absorption. This is one area where supplementation genuinely closes a gap that diet alone might not fill.

People with documented deficiencies based on blood work should supplement that specific nutrient under medical guidance. If you're iron-deficient, take iron—prescribed and monitored. If you're B12-deficient, take B12. If you're vitamin D-deficient, supplement vitamin D. But this requires diagnosis first.

Older adults may benefit from B12 supplementation or injections because absorption decreases with age. This is evidence-based and widely recommended by geriatricians.

People with certain conditions affecting nutrient absorption (celiac disease, Crohn's disease, short bowel syndrome) may need supplementation tailored to their specific condition.

Notice what's missing from this list? Healthy people eating reasonably varied diets. That's the population Primal Queen targets—people without diagnosed deficiencies, people whose problems (fatigue, mood, sex drive) have numerous potential causes that aren't being medically investigated.

The Real Solution: Food First

Here's the uncomfortable truth that the supplement industry doesn't want you to know: for most micronutrient needs, food is better than supplements.

Food contains not just individual vitamins and minerals, but thousands of phytochemicals, fiber, polyphenols, and other compounds we don't fully understand. When you eat an orange, you're not just getting vitamin C—you're getting fiber, folate, flavonoids, and compounds we still haven't named or studied. These work synergistically in ways supplements can't replicate.

Meals provide context and satiety. An egg isn't just a delivery system for choline and selenium—it's protein and fat that makes you feel satisfied. A handful of almonds isn't just vitamin E and magnesium—it's a snack that tastes good and keeps you full.

Supplements are isolated molecules in pills. Your body processes them differently. They lack the matrix of compounds that make whole foods health-promoting.

This is why the evidence for multivitamins in healthy people is so weak. Large clinical trials repeatedly show that multivitamins don't reduce heart disease, cancer, or mortality in people eating reasonably well. They just make expensive urine.

If you're tired, the first step isn't a supplement. It's examining sleep, stress, exercise, hydration, and blood work. Is your fatigue actually nutritional, or is it sleep deprivation? Thyroid dysfunction? Depression? Overwork? You can't supplement your way out of most things that make us feel lousy.

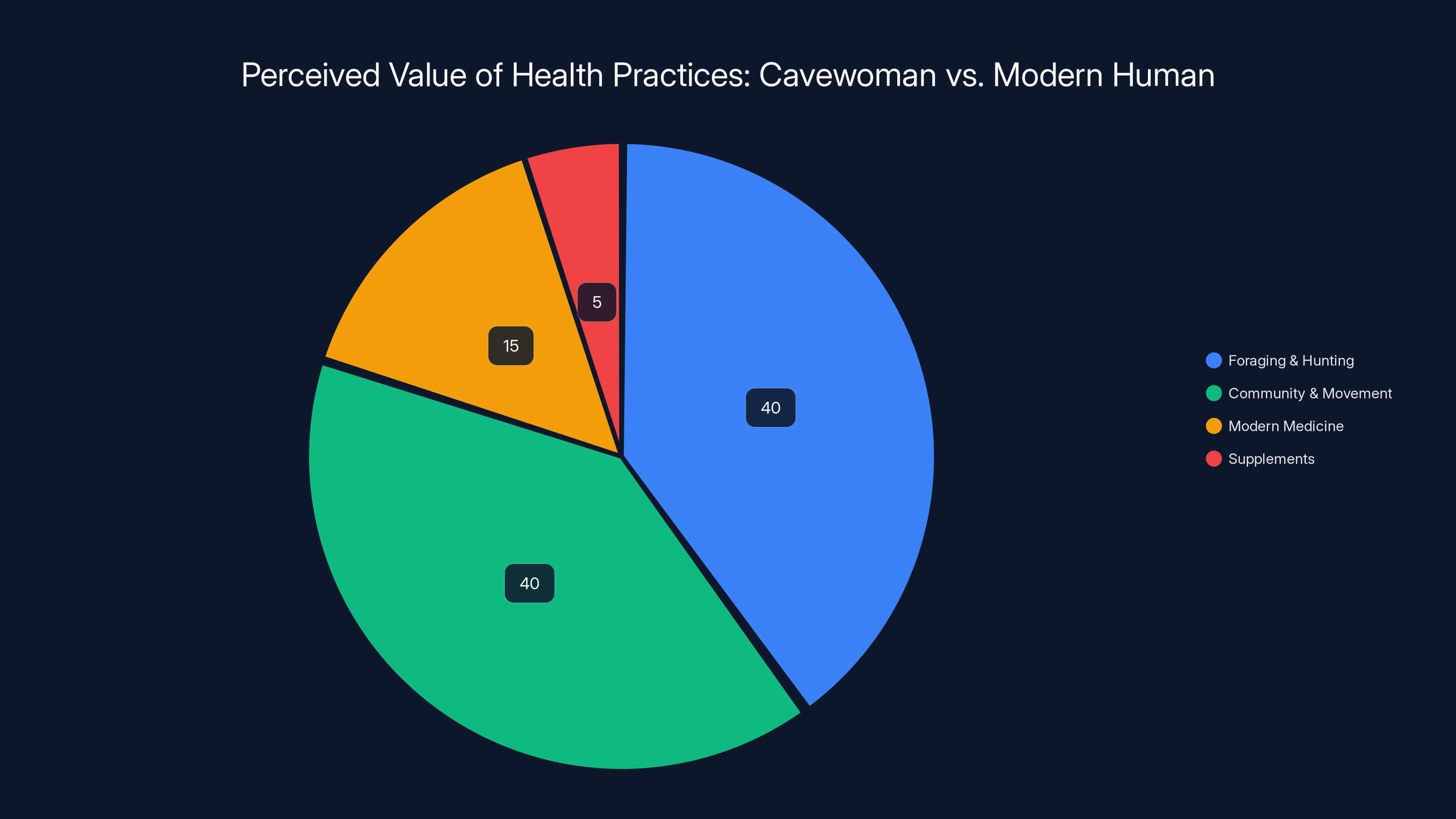

Estimated data shows that a cavewoman valued foraging and community more, while modern humans place higher value on modern medicine and supplements.

The Psychology of Health Marketing: How Companies Get Inside Your Head

Targeting Frustration and Dismissal

Primal Queen's marketing isn't accidental. It's precisely designed to appeal to a specific emotional state: frustration with healthcare.

Women, for decades, have had their health concerns dismissed. "It's all in your head." "You're just stressed." "Have you tried losing weight?" Actual medical dismissal—being told your symptoms don't matter or aren't real—is trauma. It creates a lasting sense of not being heard, not being taken seriously, not having agency over your own body.

Into this space steps Primal Queen with a message: We hear you. We believe you. You don't need a doctor telling you your symptoms aren't real. You can optimize your own health. You can be in control.

This is powerful. And it exploits real pain.

But it also sidesteps the actual solution: finding healthcare providers who listen and investigate. Advocating for yourself in medical settings. Getting second opinions. Moving to doctors who take your concerns seriously. These are harder and less immediately gratifying than buying a supplement.

Illusion of Personalization

The month-by-month timeline creates something psychologists call "illusory pattern perception." Your brain is a pattern-recognition machine. It's optimized to find connections and predict outcomes. Show it a timeline saying "expect improved sex drive in month one," and your brain will start noticing—and unconsciously seeking—evidence that this is happening.

You'll remember the one night you felt particularly interested in sex. You'll forget the nights you didn't. You'll attribute changes in sex drive to the supplement, when actually they correlate with stress, relationship dynamics, hormones, sleep, or dozens of other variables that have nothing to do with bovine uterine powder.

This is the power of personalized marketing. It doesn't feel like advertising. It feels like a protocol designed for you. It makes you complicit in tracking your own results, which actually strengthens belief in the product's effectiveness.

The Paradox of Empowerment

Supplement marketing often frames itself as empowerment. You're taking control of your health. You're not waiting for doctors or institutions. You're being proactive. You're optimizing.

But there's a dark side to this narrative. It shifts responsibility entirely to the individual. If you take Primal Queen and feel better, great—the supplement worked (maybe). If you take it and don't feel better? The implication is that you didn't take it long enough, or you didn't commit fully, or your body "needs more time." It becomes your fault for not experiencing the promised transformation.

Real empowerment includes the ability to say no. To recognize when a company is exploiting your legitimate frustrations. To distinguish between self-care and marketing-driven consumption.

What Actually Works: Evidence-Based Approaches to Fatigue, Mood, and Sexual Health

Addressing Fatigue

When someone comes to me saying they're exhausted, the first place we look isn't supplements. It's the basics:

Sleep quality and quantity. Are you getting 7-9 hours? Is it continuous or fragmented? Sleep debt accumulates. Missing an hour of sleep per night for a week makes you as impaired as missing a full night. There's no supplement that compensates for chronic sleep deprivation.

Thyroid function. Hypothyroidism causes fatigue. A simple blood test (TSH, free T4) checks this. If this is your issue, you need thyroid hormone, not a supplement.

Iron status. Women with heavy periods can develop iron deficiency anemia. Men rarely do. If you suspect iron deficiency, get blood work (ferritin, serum iron, TIBC). If you're actually deficient, iron supplementation under medical supervision is appropriate. But this requires diagnosis first.

Vitamin D. If you're deficient and in a location where sun exposure is limited, vitamin D supplementation is evidence-based.

Exercise. Counterintuitively, regular exercise increases energy. It improves sleep quality, reduces depression, improves metabolic function. There's no supplement that replaces the effect of consistent physical activity.

Stress management. Chronic stress dysregulates your nervous system and cortisol patterns. This causes fatigue. No amount of supplementation addresses untreated stress. Therapy, meditation, exercise, social connection—these are the actual treatments.

Nutrition adequacy. Are you actually eating enough? Undereating causes fatigue. Are you getting adequate protein? Carbohydrates? Iron-rich foods if you're a vegetarian? Sometimes the solution is not supplementing but eating better whole foods.

When you investigate fatigue systematically, the solution is rarely a $60 supplement. It's usually a combination of better sleep, diagnosed and treated medical conditions, exercise, stress management, and adequate nutrition.

Improving Mood

The supplement industry would like you to believe mood is a micronutrient problem. That if you just add the right minerals and vitamins, happiness follows.

That's not how depression, anxiety, or low mood works for most people.

Screen for actual depression and anxiety. These are medical conditions with evidence-based treatments. If you're experiencing persistent low mood, the first step is evaluation by a mental health professional—therapist or psychiatrist—not supplement shopping.

Exercise is more effective than antidepressants for many people. Studies comparing exercise to SSRIs show comparable efficacy. But exercise also has benefits—better sleep, stress reduction, improved self-efficacy—that pills don't provide.

Cognitive behavioral therapy and other talk therapies work. They require investment and effort, but the evidence is robust.

Adequate sleep. Sleep deprivation causes depression and anxiety. Most sleep problems are treatable through sleep hygiene, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, or, in some cases, prescription sleep aids under medical supervision. But a supplement that helps you sleep slightly better won't fix a sleep disorder.

Social connection. Loneliness is a major driver of depression. Time with people you care about—genuinely time, not scrolling on social media—improves mood. No supplement replaces human connection.

Identify actual stressors. If your mood is low because you hate your job, the solution isn't a vitamin. It's figuring out what you want to do instead.

Again, when you actually investigate mood systematically, a supplement ranks low on the list of helpful interventions.

Sexual Health and Desire

Sexual desire and function are complex. They involve hormones, blood flow, neurological function, relationship dynamics, stress levels, body image, past trauma, medication side effects, and psychological wellbeing.

Primal Queen suggests their supplement increases sex drive. But they never ask: Why is your sex drive low?

Is it hormonal? Estrogen, testosterone, and other hormones affect sexual desire. If you're in perimenopause or menopause, this is a real factor. A gynecologist can evaluate this through blood work and recommend hormone therapy if appropriate. A supplement of organ meats won't replicate the effect of hormonal balance.

Is it a medication side effect? Many antidepressants, antipsychotics, birth control pills, and blood pressure medications affect sexual function. If your sex drive dropped when you started a medication, that's likely the culprit. The solution is talking to your prescriber about alternatives or dose adjustments, not supplementing.

Is it relationship dynamics? Sometimes low desire is actually a sign that something in your relationship needs attention. This requires communication, possibly therapy, not supplements.

Is it stress or exhaustion? Hard to want sex when you're running on empty. Sleep better, stress less, you might notice desire returns naturally.

Is it body image or past trauma? Supplements don't address psychological barriers to sexual pleasure. Therapy does.

Is it vascular? Sexual function depends on blood flow. Cardiovascular exercise improves blood flow. Certain medications improve it. Some supplements might help, but this is something to discuss with a healthcare provider, not self-diagnose through supplement shopping.

Again, the actual solution to sexual health problems involves investigation and treatment, not buying a $60 bottle.

Estimated data shows that illusory pattern perception and targeting healthcare frustration are common tactics used in supplement marketing, each making up about 25-30% of strategies.

Comparing Supplements: The Honest Assessment Framework

What to Actually Check When Evaluating a Supplement

If you're considering a supplement, here's what actually matters:

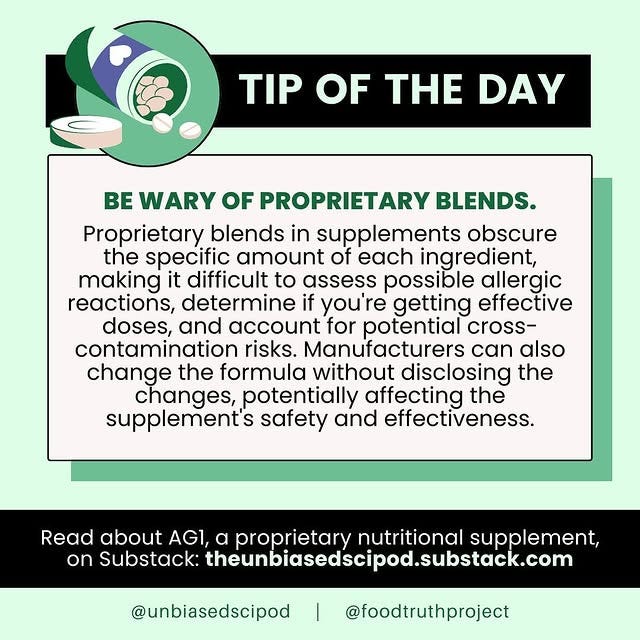

Does the product clearly list amounts of each ingredient? Proprietary blends are red flags. If a company won't tell you exactly how much of each ingredient is in their product, they're hiding something—usually because the amounts are too small to be effective, or because the expensive-sounding ingredients are present in negligible quantities.

Is there independent testing for contaminants? Third-party testing matters for purity—checking for heavy metals, pesticides, pathogens. This matters less for efficacy but more for safety.

What's the evidence for the claims being made? Not testimonials or before-and-afters. Actual clinical trials in humans. If the company can't point to peer-reviewed research supporting their claims, the claims are probably marketing.

What's the real cost per day? Calculate it. Compare it to addressing the actual need. If you suspect vitamin D deficiency, vitamin D supplements cost

What does your actual healthcare provider think? If you have a doctor you trust, ask them. If they dismiss your concerns, that's a problem with your doctor, not a validation for self-supplementing. Find a better doctor.

Is the company making disease claims? If they're claiming to treat, cure, or prevent disease, they're breaking FDA regulations. That's a company willing to violate law for profit. That's a bad sign.

Do the claims match what you actually need? If you're chronically fatigued and the supplement promises energy in week one, but fatigue has numerous potential medical causes, you're not addressing the root problem. You're hoping a supplement fixes something that might need medical investigation.

Red Flags Everywhere

Think critically about supplement marketing. Here are the things that should immediately make you skeptical:

- "Ancient wisdom" (appeals to nature fallacy)

- "Lab-made vs. natural" framing (meaningless distinction)

- Month-by-month timelines showing exactly when results appear (illusory pattern perception)

- Celebrities or influencers endorsing them (paid advertising, not independent recommendation)

- Vague health benefits ("vitality," "wellness," "balance")

- "Clinically proven" without linking to the actual clinical trials

- Proprietary blends hiding amounts (transparency issue)

- Before-and-after photos (selection bias, lighting, angles)

- Money-back guarantees (companies betting you'll forget to request refunds)

- Urgency or limited-time offers (scarcity principle)

When you see these tactics, you're watching persuasion, not information.

The Future of Supplement Regulation: What Might Change

Current Momentum for Tighter Rules

There's growing recognition that the current regulatory environment is broken. The FDA lacks resources to police the supplement industry meaningfully. States are moving independently to create stricter standards. And consumer groups are pushing for change.

Potential future developments:

Mandatory efficacy evidence for new supplement claims. Some are proposing that supplements be held to similar evidence standards as over-the-counter drugs. This would eliminate the weakest products but would also mean supplement companies need actual clinical trial data before making claims.

Standardized labeling and dosing. If you buy a supplement in 2025, there's no guarantee that the amount of each ingredient is consistent across batches. Standardization would be a major shift.

Ingredient transparency requirements. No more hiding amounts in proprietary blends. Companies would need to disclose exact amounts, exactly as pharmaceutical companies do.

Better adverse event reporting. Currently, if you have a bad reaction to a supplement, it's hard to report it and hard for the FDA to track trends. Better reporting would catch dangerous products faster.

None of this is guaranteed. The supplement industry is powerful and well-lobbied. But pressure is building.

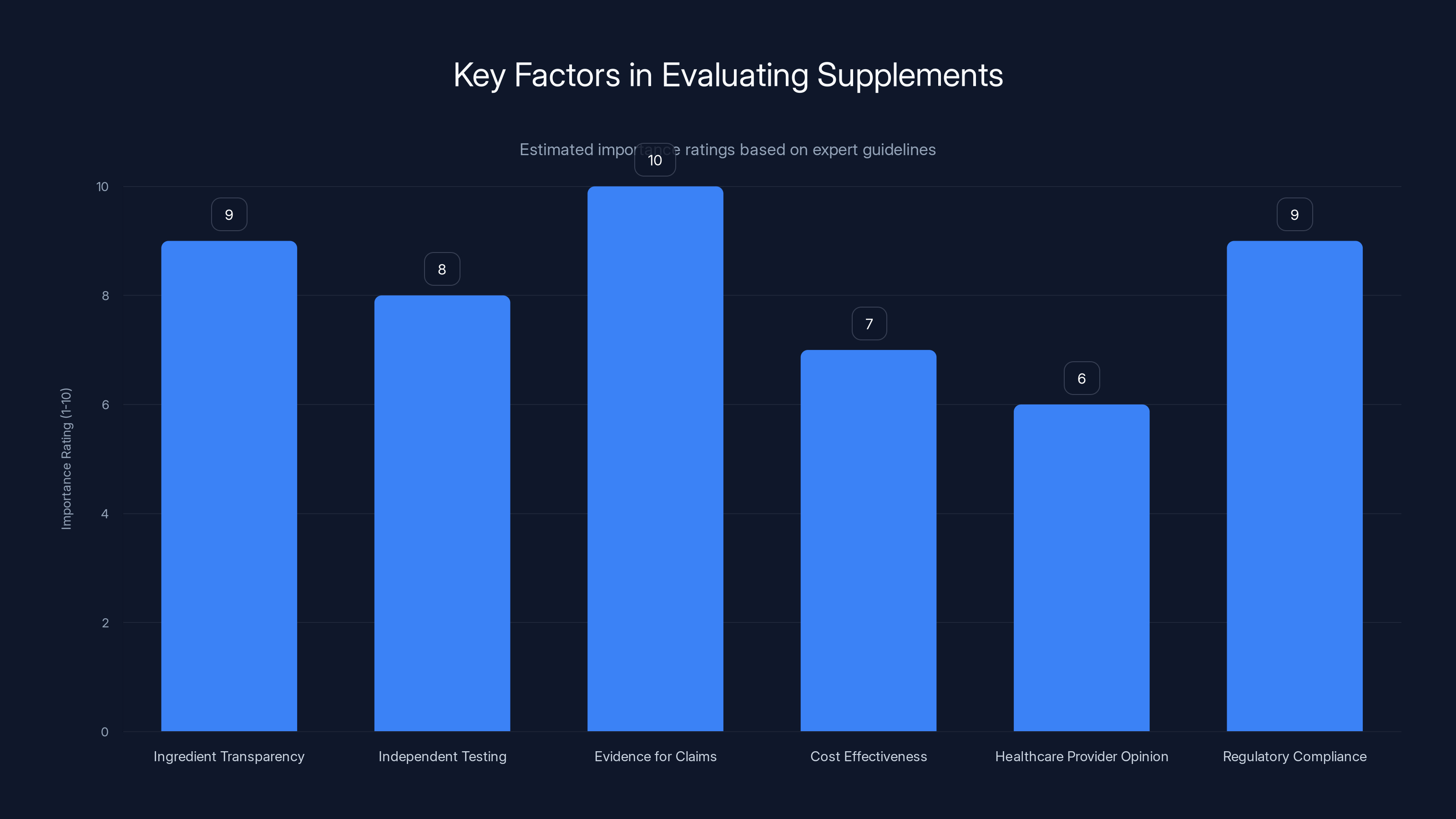

Ingredient transparency and evidence for claims are crucial factors when evaluating supplements. Estimated data based on expert guidelines.

Building Real Health: The Evidence-Based Alternative

The Unsexy, Proven Approach

If Primal Queen had honest copy, it would look like this:

"Our product contains nutrients you're probably getting from food anyway. If you're not actually deficient in these nutrients, taking more won't improve your health. Most Americans aren't deficient. We don't have clinical evidence that this product improves energy, mood, sex drive, or any of the things we claim. But it's natural, which feels good, so take it if you want. It costs

Nobody would buy it.

The actual path to better health is less Instagram-friendly:

Get blood work. Baseline labs—CBC, metabolic panel, thyroid function, vitamin D, iron studies—take about 30 minutes and cost $100-300. They tell you what's actually happening in your body instead of guessing.

Address actual deficiencies medically. If blood work shows vitamin D deficiency, take vitamin D. If it shows iron deficiency, take iron. If it shows B12 deficiency, supplement B12. But this requires knowing what you're treating.

Improve diet quality. More whole foods, more vegetables, more legumes, adequate protein. This is boring. It's not a proprietary formula or an ancestral secret. But it works and it's cheap.

Exercise consistently. 150 minutes of moderate activity per week or 75 minutes of vigorous activity. Walk. Lift. Run. Dance. Yoga. Whatever you'll actually do. Exercise is the closest thing we have to a wonder drug—it improves cardiovascular health, mood, sleep, metabolism, bone density, cognitive function, and energy.

Prioritize sleep. 7-9 hours per night. Consistent schedule. Cool, dark room. Screens off an hour before bed. This is where most people can move the needle most easily.

Manage stress. Therapy, meditation, exercise, time in nature, time with people you care about. Not a supplement—genuine stress reduction.

Address mental health directly. If you're struggling with mood or anxiety, see a mental health professional. Not a supplement company. A therapist or psychiatrist who can actually help.

This path is less profitable for the supplement industry. It doesn't require recurring purchases of expensive bottles. It requires effort—real effort, not the imaginary effort of swallowing a pill and watching your timeline of benefits unfold.

But it actually works.

The Bottom Line: What a Cavewoman Would Actually Think

The premise of Primal Queen is that a cavewoman would approve of their supplement. That ancestral wisdom supports this product.

Let's actually think about that.

A woman 10,000 years ago didn't take supplements. She foraged for diverse plant foods. She hunted and ate meat when she could—consuming the entire animal, including organs. She didn't live longer because of this. Average lifespan was maybe 30-40 years. Infant mortality was catastrophic. Nutritional deficiency was common. Dental health was poor. Infection was deadly.

If we could somehow show her modern healthcare, she'd be astounded. Antibiotics. Anesthesia. Vaccination. Childbirth without dying. The ability to treat iron deficiency with actual medical care instead of guessing. Access to diverse foods year-round instead of seasonal foraging.

What she absolutely would not understand is the concept of a $60 bottle of powdered organs sold through Instagram as an optimization hack. She'd recognize it for what it is: marketing. Persuasion. An appeal to a false sense of ancestral authenticity.

The irony is devastating. Primal Queen claims to connect you to your ancestors while selling you industrial processed supplements that your ancestors would never recognize. They're marketing primitivism while operating on entirely modern consumer psychology principles.

The real ancestral wisdom—if such a thing exists—would be: eat what's available, move your body, stay connected to community, and accept that health is luck, circumstance, and biology.

What a modern human should do is actually simpler: investigate your actual health status through blood work, eat well, exercise, sleep, manage stress, and see a doctor when something is wrong. That's it. No $60 supplements needed.

The supplement industry makes billions by convincing you that optimization requires buying their product. The honest truth is that for most people, the path to better health isn't a new supplement. It's the unglamorous, proven basics: better sleep, consistent exercise, stress management, whole food nutrition, and actual medical care when you need it.

That won't get you viral on Tik Tok. It won't look sophisticated on Instagram. But it works.

And that's really all that matters.

FAQ

What is the appeal to nature fallacy?

The appeal to nature fallacy is a cognitive bias that assumes anything natural is automatically better, safer, or more effective than synthetic alternatives. However, this isn't true—arsenic and mercury are natural, while many synthetic compounds like antibiotics save lives. The fallacy exploits our evolutionary history, when "natural" usually meant "safe to eat," but that heuristic breaks down in the modern world where we've created both beneficial synthetics and dangerous natural substances.

How do supplements like Primal Queen exploit marketing psychology?

These supplements use multiple psychological tactics: month-by-month timelines create illusory pattern perception, making you unconsciously seek evidence that the product works; vague health benefits like "vitality" and "well-being" can't be disproven; appeals to ancestral wisdom exploit nostalgia; and targeting women frustrated with healthcare validation uses real pain for profit. The marketing framework is designed to make you complicit in tracking your own results, strengthening belief in the product's effectiveness regardless of actual efficacy.

What does third-party testing actually verify?

Third-party testing checks whether a supplement contains the labeled amounts of ingredients and isn't contaminated with heavy metals or pathogens. It does not verify that the supplement actually works or produces health benefits. It's a quality assurance and purity test, not an efficacy test. Companies can honestly advertise "third-party tested" while making unproven health claims.

Why are supplements regulated differently than pharmaceuticals?

Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) from 1994, supplements are presumed safe until proven otherwise, with the FDA bearing the burden of proving harm. Pharmaceuticals work oppositely—companies must prove efficacy and safety before FDA approval. This means supplement companies can make structure-function claims without clinical evidence, they can use proprietary blends that hide ingredient amounts, and they face minimal enforcement unless they explicitly claim to treat disease or cause harm.

What nutritional deficiencies are actually common in Americans?

Actually, most Americans eating reasonably varied diets don't have serious micronutrient deficiencies. Less than 1% have vitamin A deficiency. Vitamin B12 deficiency is rare except in vegans and people with certain digestive conditions. Zinc deficiency affects roughly 15-20% of certain populations but is uncommon overall. Vitamin D deficiency is genuinely common in northern climates and certain demographic groups. Iron deficiency occurs in women with heavy periods and some infants. Folate deficiency is rare since food fortification. If you suspect a deficiency, blood work is the answer, not guessing through supplementation.

What actually works for fatigue, mood problems, and low sex drive?

For fatigue: check sleep quality and quantity, thyroid function, iron status, vitamin D levels, stress management, and exercise—supplements are low on the list. For mood: screen for depression and anxiety with a mental health professional, prioritize exercise and sleep, examine stress and life circumstances. For sexual health: investigate hormonal status, medication side effects, relationship dynamics, stress, and cardiovascular health—all require actual investigation, not supplement shopping. Most of these require medical evaluation or lifestyle changes, not purchasing a proprietary formula.

How should I evaluate whether a supplement is worth buying?

Check whether ingredients are clearly labeled with specific amounts (not proprietary blends), whether there's independent testing for contaminants, whether claims are backed by peer-reviewed clinical trials (not testimonials), calculate the actual daily cost compared to addressing specific deficiencies, and ask your healthcare provider what they think. Be skeptical of month-by-month timelines, vague health benefits, celebrity endorsements, ancient wisdom appeals, and before-and-after photos. If a company won't clearly state what's in their product or how much, that's a red flag.

What's the evidence-based approach to better health?

Get baseline blood work to know your actual health status instead of guessing. Address any documented deficiencies medically. Improve whole food nutrition—more vegetables, legumes, and whole grains. Exercise consistently (150 minutes moderate or 75 vigorous per week). Prioritize sleep (7-9 hours nightly). Manage stress through therapy, meditation, or activity. If you're struggling with mood or anxiety, see a mental health professional. This approach isn't glamorous or as profitable for the supplement industry, but it's what actually improves health according to decades of research.

The Real Path Forward

The supplement industry isn't going anywhere. Billions of dollars ensure that marketing will continue, claims will stretch the edge of regulation, and new products will keep appearing on your feed.

But you can protect yourself by thinking critically. By asking harder questions. By recognizing marketing psychology when you see it. By understanding that "natural" doesn't mean safe or effective. By getting blood work instead of guessing. By addressing actual health problems through proven methods instead of hoping a supplement fixes something you haven't investigated.

The cavewoman reference in Primal Queen's marketing is clever. It appeals to something deep—a sense that we've lost our way, that modern life has made us sick, that going back to basics will save us.

But that narrative ignores that our ancestors didn't live better. They lived shorter. They suffered from infections we can now cure. They didn't have antibiotics, pain relief, or the ability to treat serious illness. Modern medicine and modern food systems—imperfect as they are—have extended human lifespan and reduced suffering in ways our ancestors could never have imagined.

The real optimization isn't returning to the past. It's using what we've learned—about sleep, exercise, nutrition, mental health, and medicine—to actually take care of ourselves.

That's the real primal wisdom: attention to the basics, sustained over time, with actual investigation when something goes wrong.

No $60 supplement required.

Key Takeaways

- The appeal to nature fallacy—assuming 'natural' is automatically better—is the core marketing strategy behind expensive supplements like Primal Queen, exploiting cognitive biases and real frustration with healthcare dismissal

- Most Americans aren't nutritionally deficient: less than 1% lack vitamin A, B12 deficiency is rare outside vegans, and zinc deficiency affects only 15-20% of certain populations—making expensive supplements unnecessary for the average person

- Supplements operate in a regulatory gray zone where companies can make health claims without clinical evidence, use proprietary blends hiding ingredient amounts, and face minimal FDA oversight compared to pharmaceuticals

- Month-by-month benefit timelines create illusory pattern perception, making your brain unconsciously seek evidence that vague claims like 'better mood' and 'vitality' are working, regardless of actual efficacy

- Real solutions for fatigue, mood issues, and sexual health require medical investigation (blood work, diagnosis) and proven interventions (exercise, sleep, stress management, therapy)—not $2-per-day supplement gambling

Related Articles

- AI Kids' Toys Safety Crisis: Explicit Responses & Hidden Risks [2025]

- Jinu: The Tragic Demon Idol of K-pop Demon Hunters [2025]

- Jinu K-Pop Demon Hunters: Character Guide & Viral Moments [2025]

- Chiikawa: The Complete Character Guide & Series Overview [2025]

- Kyojuro Rengoku: The Flame Hashira's Legacy [2025]

- Why Rengoku's Death Hit So Hard: Demon Slayer's Masterpiece [2025]

![The $60 Supplement Myth: Why 'Natural' Isn't Always Better [2025]](https://runable.blog/blog/the-60-supplement-myth-why-natural-isn-t-always-better-2025/image-1-1765653499715.jpg)