Introduction: The Moment Your Privacy Hit Home

Imagine signing up for a new financial service, clicking through terms and conditions you didn't read, and suddenly seeing a complete list of every credit card in your wallet displayed on your screen. The card names. The last four digits. Everything.

That feeling of violation is real, and it's happening to thousands of people right now.

This isn't some dystopian fiction. It's happening through companies like Bilt, a rental rewards platform that's quietly changed how we think about privacy in fintech. But here's what's shocking: Bilt isn't doing anything technically illegal. They're not hacking your bank account or bribing your credit card companies. They're simply using data that's been legally available all along, buried in terms of service documents that almost nobody actually reads.

The bigger question isn't just how Bilt knows your cards. It's how any company knows your cards. And more importantly, how many other companies are doing this without you even realizing it.

This isn't just about one startup or one creepy feature. It's about understanding the entire infrastructure of consumer data in America—where it comes from, who has access to it, what they can legally do with it, and most critically, what you can do to protect yourself.

Over the next few sections, we're going to walk through exactly how this works. You'll learn about the data brokers operating in the shadows, the credit reporting agencies that know more about you than you know about yourself, the legal framework that allows all of this, and the practical steps you can take starting today to reclaim some control over your financial privacy.

Because here's the thing: knowing is half the battle. And most people have no idea how exposed they actually are.

TL; DR

- Credit card data flows through multiple sources: Credit bureaus, card networks (Visa, Mastercard), card issuers, and third-party data aggregators all legally collect and share your financial information, as detailed by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

- Method Financial and similar aggregators are the middlemen: Companies use data aggregation services that pull card information from multiple sources with your consent buried in terms of service, as noted in the Troutman Pepper newsletter.

- It's all technically legal: The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) and other regulations create "permissible purposes" that allow companies to access your financial data if you've agreed to their terms, as explained in Federal News Network.

- Consent is often implicit, not explicit: Most people never realize they've granted permission because the language is buried in lengthy terms and conditions, as highlighted in Nav's terms.

- You have real options to protect yourself: From using bank account transfers instead of card linking to opting out of data sharing, you're not completely powerless, as suggested by LendingTree.

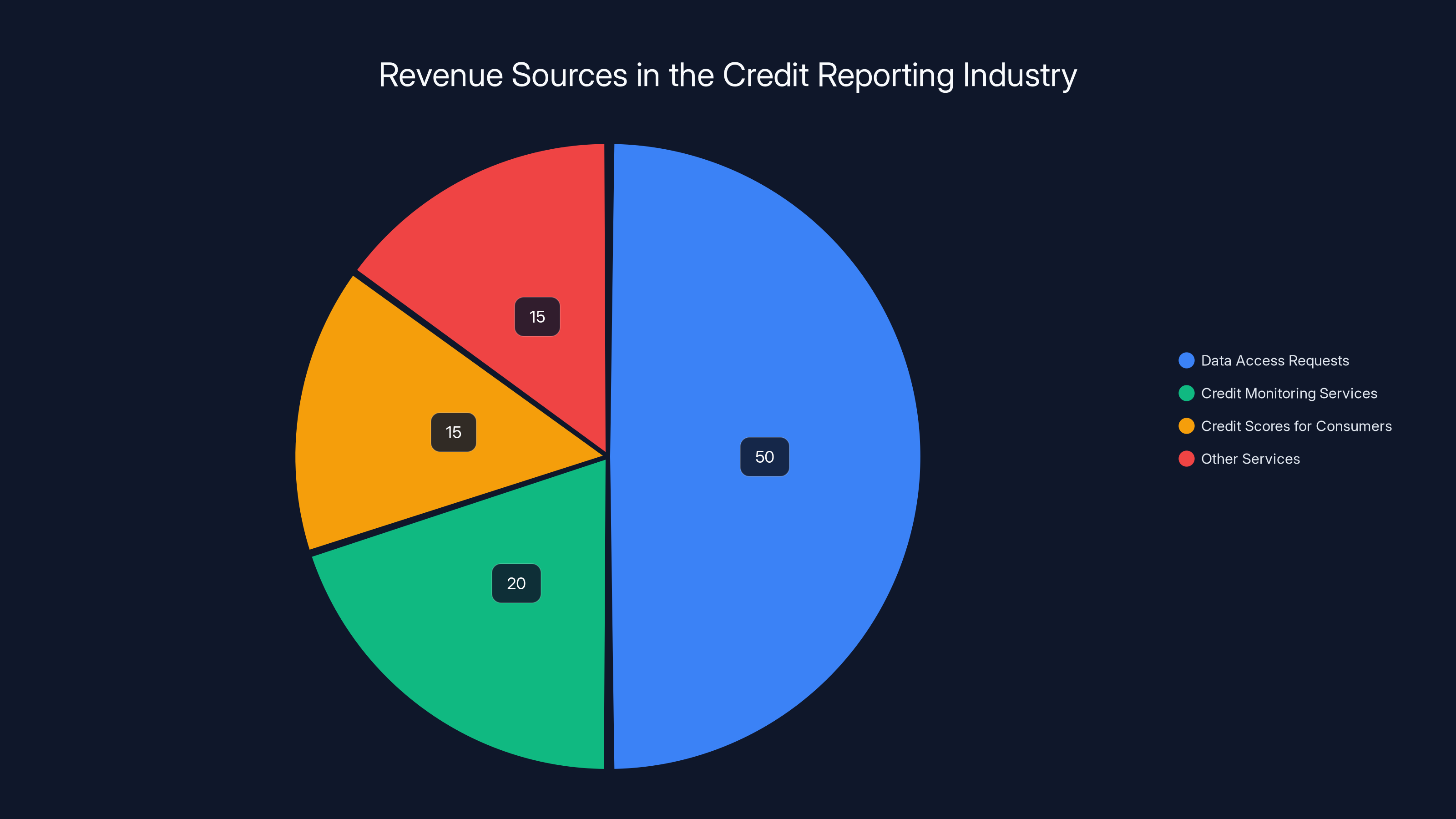

Estimated data shows that data access requests account for approximately 50% of the credit reporting industry's $19 billion annual revenue.

The Architecture of Financial Data in America

Before we can understand how a startup knows what's in your wallet, we need to understand the entire ecosystem that makes this possible. It's not a single company or even a single database. It's a complex network of organizations that collect, aggregate, package, and sell consumer financial information every single day.

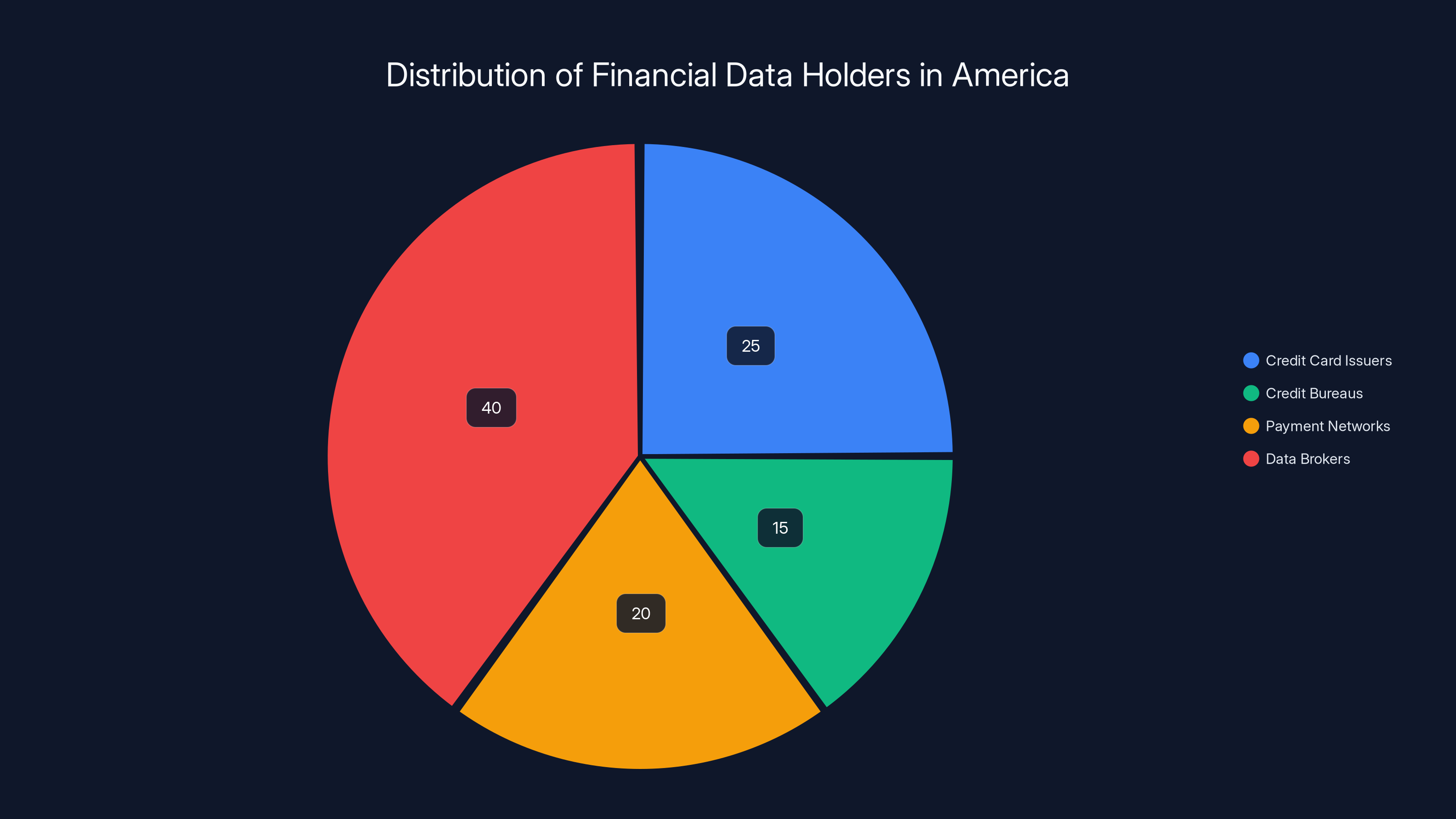

Think of it like this: your financial information doesn't belong to you anymore. It belongs to a distributed network of companies, each holding different pieces of the puzzle. Your credit card issuer (Bank of America, Chase, Capital One) knows your payment history. The credit bureaus (Equifax, Experian, Trans Union) know your credit score and defaults. Visa and Mastercard know your transaction patterns. And the data brokers know how to connect all of these dots.

This system evolved over decades, starting with credit bureaus that needed to share information to prevent fraud, then expanding to serve marketing purposes, underwriting decisions, and increasingly, just about every business that wants to understand consumer behavior, as discussed in Drug Channels.

The result is an almost total financial transparency of American consumers. There are very few ways to exist in this economy without leaving a complete trail of your financial activities.

What makes this system particularly opaque is that most of these data flows happen behind the scenes. You never see them. You don't get a notification when Equifax sells access to your data. You don't know when a third-party aggregator pulls your card information. The entire infrastructure is built on the principle that consumers don't need to know how their data is being used, as long as they technically agreed to it somewhere in a terms of service document.

The Three Layers of Financial Data Collection

To understand how companies access your credit card information, you need to understand the three distinct layers of the financial data ecosystem.

The Primary Data Layer consists of the entities that directly interact with you and collect your information in real-time. Your credit card issuer. Your bank. The payment processors. These are the companies that know exactly what you bought, when you bought it, and how much you spent. They have the most accurate, most current information about your financial activities.

When you swipe a credit card at a store, that transaction creates a record. Your card issuer knows about it immediately. Visa or Mastercard knows about it. The merchant knows about it. This primary layer is where financial data originates.

The Secondary Data Layer consists of the credit reporting agencies and credit bureaus that aggregate and package this information. Equifax, Experian, and Trans Union buy access to payment data, default information, and credit inquiries. They don't create the data—they aggregate it from primary sources. But they structure it in ways that make it valuable for credit decisions, risk assessment, and increasingly, marketing purposes.

These agencies maintain files on hundreds of millions of consumers. They know your payment history going back years. They know every time someone checks your credit. They know about defaults, collections, and judgments. This information gets compiled into the credit report that directly affects your ability to get loans, rent apartments, or even get hired for certain jobs.

The Tertiary Data Layer is where it gets really interesting. This is the world of data brokers, data aggregators, and fintech companies that build tools to access the information held by primary and secondary sources. This is where companies like Method Financial operate. They don't collect your data directly. They don't maintain massive databases of your financial information. Instead, they build bridges to all the other databases.

Method Financial, which powers the card-linking feature for Bilt and dozens of other fintech companies, acts as an intermediary. They have agreements with credit bureaus, card networks, and card issuers that allow them to query their systems on behalf of consumers. When you link your cards to Bilt, Method Financial runs a process that essentially asks: "Hey Equifax, what cards does this person have? Hey Visa, what cards does this person have? Hey Chase, what accounts does this person have?"

The answers come back, and suddenly you're seeing a complete picture of your financial wallet.

Estimated data shows that data brokers hold the largest share of consumer financial data, highlighting the complexity and opacity of the financial data ecosystem.

The Legal Framework: Why This Is Totally Legal (And Kinda Messed Up)

Here's what most people don't realize: everything we've just described is completely legal. There's no gray area, no technical loophole, no corporate malfeasance. It's all built on a legal foundation that was created decades ago and hasn't been fundamentally updated for the modern era.

The legal basis for all of this comes from the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), passed in 1970. The FCRA is actually a consumer protection law. It was created to protect consumers from unfair credit practices. But it also created the legal framework that allows credit bureaus and data brokers to operate.

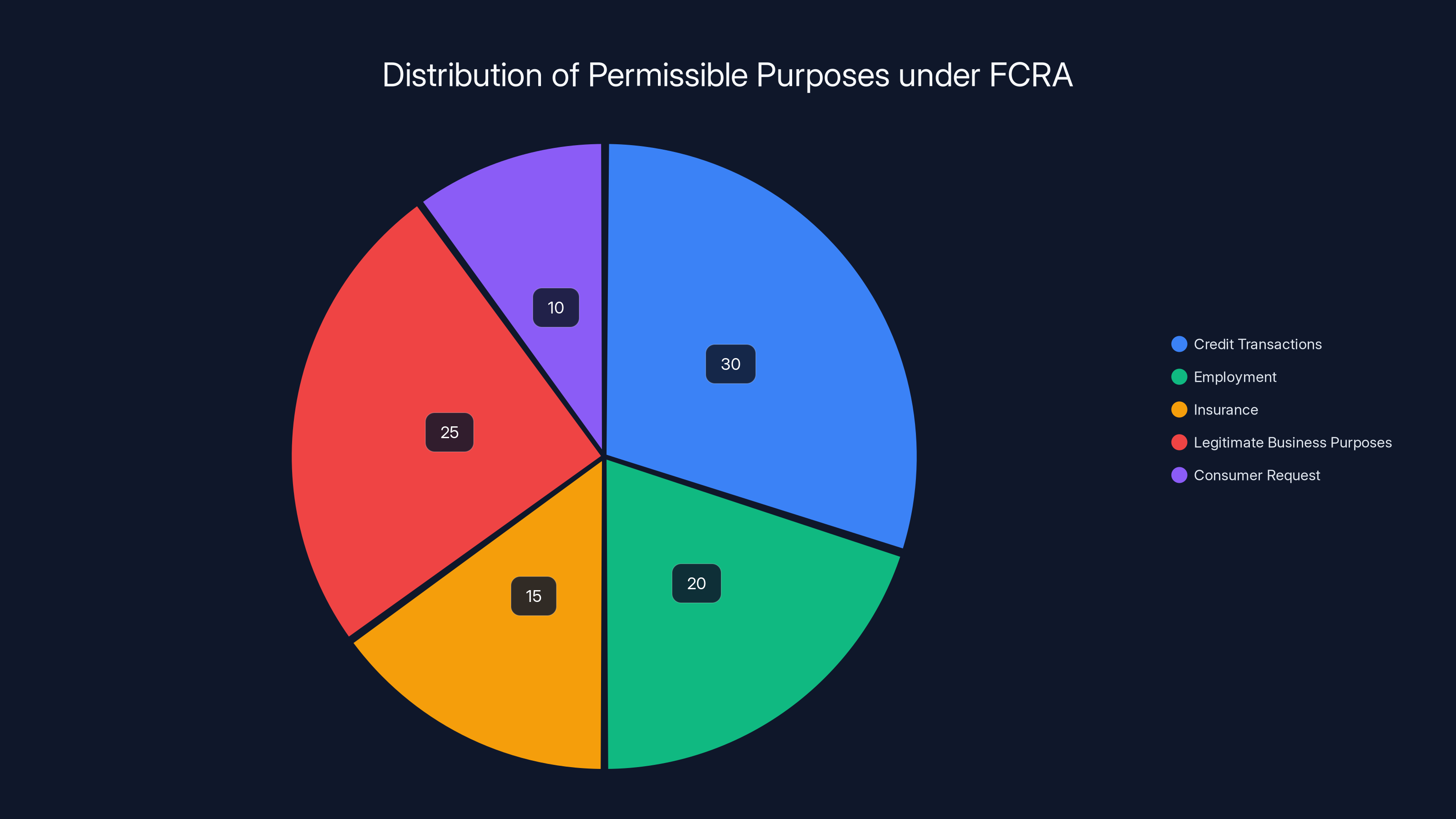

The FCRA established the concept of "permissible purposes"—specific reasons why an entity is allowed to access your credit information. These permissible purposes include:

- Credit transactions: Granting credit, collecting debts, or determining credit-worthiness

- Employment: Evaluating job applicants or employees

- Insurance: Underwriting or rating insurance policies

- Legitimate business purposes: Matching records, fraud prevention, account verification

- Consumer request: When you directly ask for access to your own information

But here's the thing: the definition of "legitimate business purposes" is broad enough to drive a truck through. And it gets even broader when you consider how many companies claim legitimate business purposes.

When you sign up for Bilt, you're technically agreeing to let them access your credit information for the purpose of providing their service and optimizing their rewards program. The card-linking feature isn't hiding this anywhere—it's right there in the terms and conditions. But because almost nobody reads terms and conditions, it might as well be invisible.

The Permissible Purpose Expansion

The FCRA created permissible purposes, but it didn't anticipate how broadly those purposes would be interpreted over the following decades. Originally, permissible purposes were fairly narrow—you needed to access someone's credit information for a specific, well-defined reason like lending or employment.

But as the fintech industry exploded, companies found creative ways to claim legitimate business purposes. A rewards startup like Bilt can argue that knowing your complete financial picture is necessary to optimize their rewards matching and fraud prevention. A rental platform can argue that understanding your complete financial health is necessary for leasing decisions. An insurance company can argue that knowing all your accounts is necessary for risk assessment.

And technically, these arguments aren't wrong. But they're also not the only permissible purpose being claimed. The same data is being accessed for purposes that weren't contemplated when the FCRA was written in 1970:

- Behavioral targeting: Using your financial data to show you targeted advertisements

- Merchant partnerships: Selling aggregated insights to local businesses

- Product optimization: Using anonymized aggregates of your spending to improve services

- Cross-selling: Using your financial profile to recommend products and services

None of these purposes existed in 1970. The FCRA is old enough to be someone's grandfather, and it's trying to regulate an industry that didn't exist when it was written.

How Data Aggregators Actually Work

Now that you understand the legal framework, let's talk about the mechanics of how companies like Method Financial actually access your data. Because understanding the technical process is key to understanding why this feels so invasive.

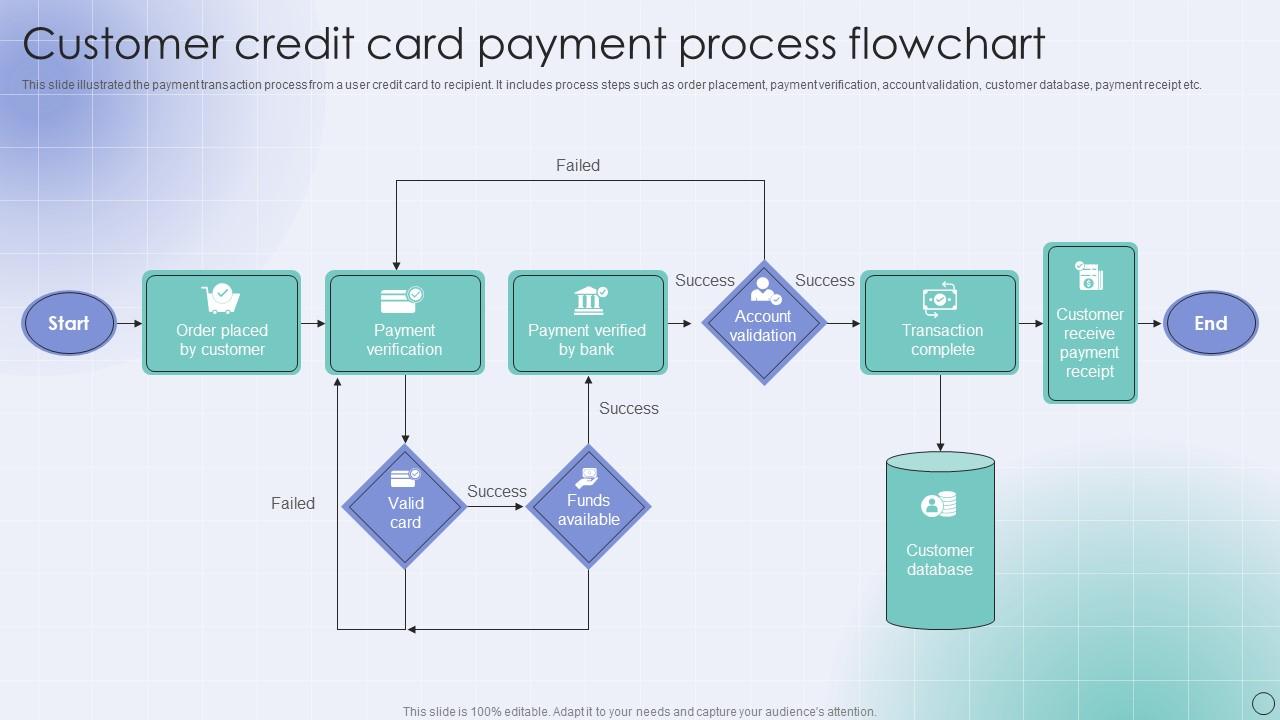

When you link your credit cards to Bilt, you're not directly connecting your cards to Bilt's servers. Instead, you're initiating a data aggregation process through Method Financial. Here's what happens:

Step 1: Authentication and Consent

You enter your information into the Bilt app. This triggers Method Financial to reach out to the credit bureaus and card networks on your behalf. At this point, you've technically consented to this process by agreeing to Bilt's terms of service, which included authorization for Method Financial to act as your agent.

This is where the language matters. Bilt doesn't say "we're going to access the credit bureaus without your consent." They say "upon your consent, we work with Method Financial to retrieve this information for you." Consent is there, technically. It's just not informed consent in any real sense, because most users don't understand what they're consenting to.

Step 2: Data Source Queries

Method Financial has pre-established relationships with multiple data sources:

- Credit bureaus (Equifax, Experian, Trans Union): These maintain comprehensive files on every consumer. Method Financial can query their systems to ask: "What credit accounts does this person have?"

- Card networks (Visa, Mastercard): These maintain records of card issuers and products. Method Financial can query for: "What cards has this person been issued by participating issuers?"

- Card issuers (Chase, Bank of America, Capital One): Major issuers have direct connections or data-sharing agreements with aggregators. They can be queried for account information.

- Open banking APIs: Some banks provide direct API access to account information through services like Plaid, which Method Financial may leverage.

The aggregator essentially runs a distributed query across all these sources simultaneously.

Step 3: Data Aggregation and Presentation

The responses come back to Method Financial, which then aggregates the data and presents it back to Bilt. Your cards appear in your account, usually within seconds or minutes. The data includes:

- Card brand (Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover)

- Card type (Premium Rewards, Business, etc.)

- Last four digits of the card number

- Issuing bank

- Account status (active, closed, etc.)

All of this data came from legitimate sources that legally have this information. Method Financial isn't stealing it or hacking it. It's requesting it through authorized channels using the permissible purposes established by the FCRA.

Step 4: Data Usage and Sharing

Once Bilt has your card information, they can use it for:

- Showing you your own cards (convenience)

- Routing your transactions to reward-eligible merchants

- Preventing fraud by detecting unusual patterns

- Matching you with rewards opportunities

- Sharing anonymized, aggregated insights with merchant partners

They're not supposed to sell your raw card data to third parties. But they can share aggregated insights (like "building residents in this area spend 23% more at coffee shops than the city average") with their merchant partners to optimize targeting.

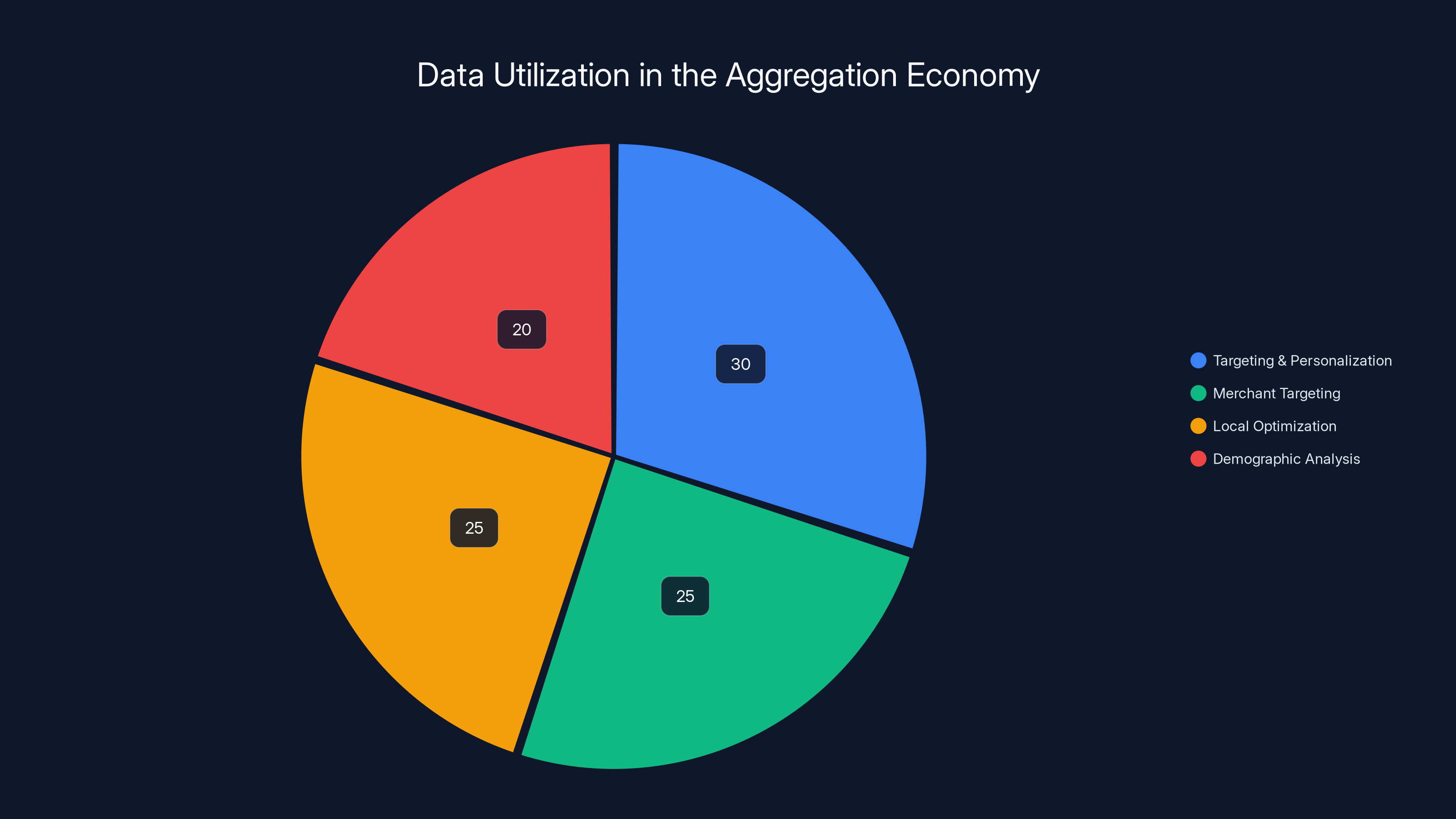

The pie chart illustrates the estimated distribution of permissible purposes under the FCRA. 'Legitimate Business Purposes' accounts for a significant portion, highlighting its broad interpretation. Estimated data.

The Data Sources Behind the Curtain

Understanding how data aggregators work is important, but understanding where they get their data is even more critical. Because here's the uncomfortable truth: the companies providing this data aren't getting it without authorization. They've got agreements that allow them to share your information with aggregators.

Credit Bureaus and Your Complete Financial History

Equifax, Experian, and Trans Union are the most comprehensive data sources for financial information. They maintain detailed files on over 200 million American consumers. These files don't just include credit history—they include:

- Every credit account you've ever opened (along with the dates and credit limits)

- Every payment you've ever made (or missed)

- Every time someone checked your credit

- Collection accounts and charge-offs

- Public records like judgments and liens

- Recent inquiries for credit

- Your address history going back years

- Employment information

- Aliases and variations of your name

When Method Financial queries the credit bureaus for your card accounts, they're tapping into the most comprehensive consumer financial database in the world. The bureaus maintain this data because they have permissible purposes to do so. Banks report account information to build credit files. Credit issuers report defaults. Debt collectors report collection accounts.

The bureaus then share this data with a wide variety of entities for permissible purposes. And one of those permissible purposes is to provide information to companies like Method Financial, which are acting on behalf of consumers who've consented to the access.

Why do the credit bureaus allow this? Because they make money from it. Every query costs something. Every piece of data accessed generates revenue. The credit reporting industry generates over $19 billion in annual revenue, much of it from these kinds of data access requests, as reported by Morningstar.

Card Networks and the Issuer Connection

Visa and Mastercard sit at the center of the card payments system. They don't issue cards themselves (with rare exceptions), but they maintain comprehensive knowledge of what cards exist, who issued them, and what merchants accept them.

When a card aggregator needs to know what cards a person has, they can query Visa and Mastercard's systems. The card networks maintain this information because:

- Fraud prevention: The networks need to know about active cards to detect fraudulent usage patterns

- Merchant categorization: They need to match cards to merchants for rewards and dispute purposes

- Network optimization: They analyze transaction patterns to improve their networks

But they also maintain these records because they can monetize them. Aggregators pay for access. Marketing companies pay for insights. Merchants pay for customer matching.

One important note: Visa and Mastercard don't have your card numbers. They have information about what types of cards you have, what banks issued them, and demographic information about cardholders. But the detailed transaction history stays with the card issuer.

Card Issuers and Direct Data Sharing

This is where it gets real. Major credit card issuers like Chase, Bank of America, American Express, and Capital One don't just share your data with aggregators. They have direct data-sharing agreements.

When you apply for a credit card, you're signing agreements that authorize the issuer to share your information with affiliated companies, service providers, and third parties for specific purposes. These purposes include:

- Service delivery and account management

- Fraud prevention

- Payment processing

- Product optimization

- Marketing (often with opt-out provisions)

- Third-party sharing (often with opt-out provisions)

The vast majority of card issuers will share your basic account information (card type, account status, last four digits) with data aggregators as long as there's a legitimate business purpose and the consumer has consented.

In fact, many major issuers have relationships with fintech companies specifically designed to facilitate this kind of sharing. Chase has business relationships with dozens of fintech partners. American Express shares data with selected third parties for product optimization. Capital One provides account data to aggregators.

This is legal and sanctioned by the issuers because they see it as a way to create value for their customers. If Bilt can show you rewards opportunities specifically tailored to your financial situation, that's valuable. If Method Financial can help match your cards to benefits, that's valuable. And the card issuers make money from the transaction volume these platforms generate.

The Privacy Paradox: What You're Actually Agreeing To

Here's where the system gets really insidious, and where your own behavior might be working against you.

When you sign up for Bilt or any similar financial service, you encounter what we call the "consent wall." You have to agree to terms and conditions to proceed. These terms typically include authorization for the company to access your financial data.

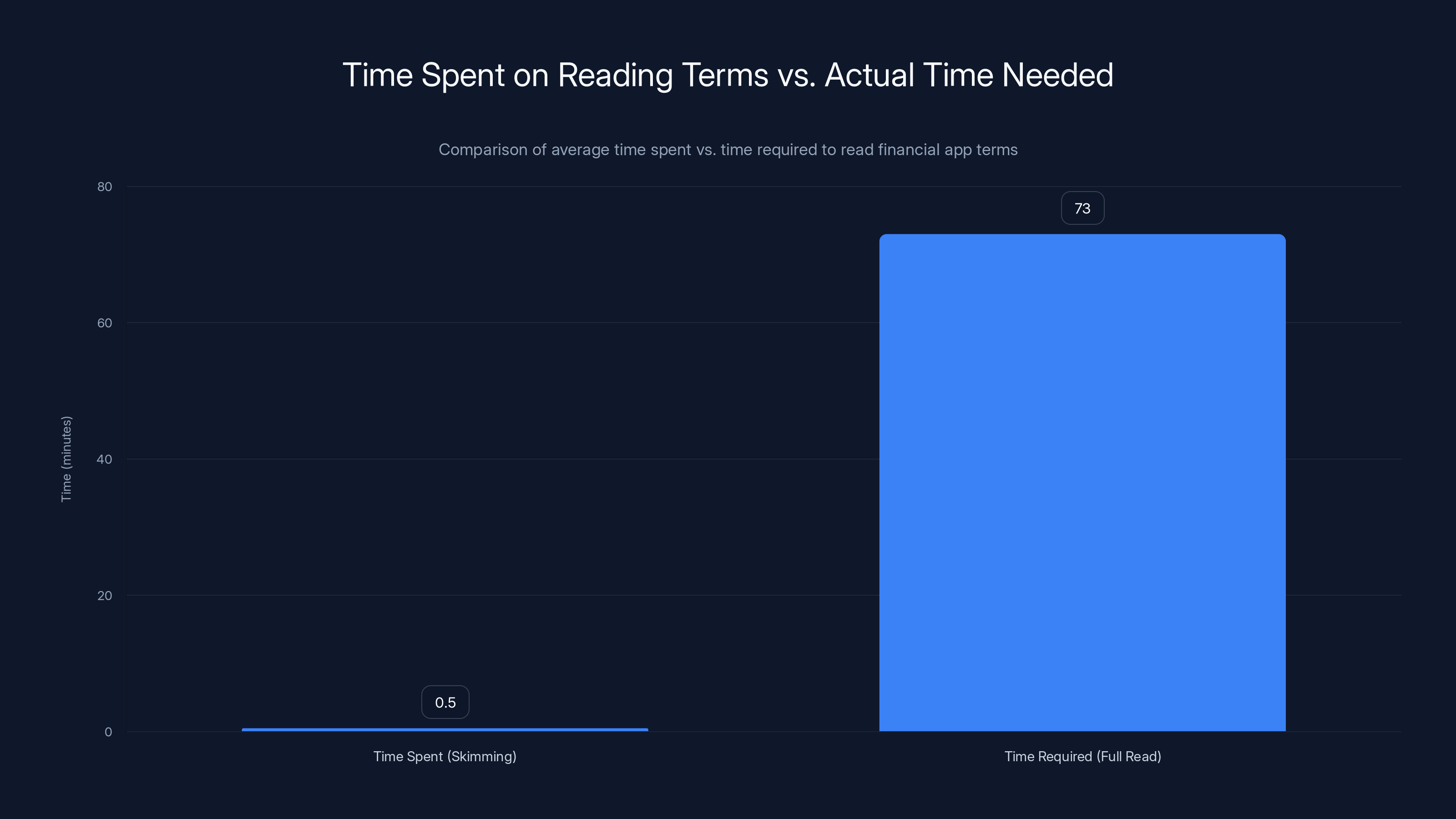

But here's the thing: research shows that the average terms of service document for a financial app is over 10,000 words long. It takes the average person approximately 73 minutes to read through them completely. Most people spend about 30 seconds skimming before clicking "I agree."

Those terms and conditions are intentionally written in dense legal language. They're not trying to be understood by regular people. They're written by lawyers for lawyers, structured in a way that provides maximum legal protection while minimizing the chances that regular people will understand what they're agreeing to.

Inside those terms, there's typically language like:

"You authorize us to access your financial data from third parties, including credit reporting agencies, payment networks, and financial institutions, in order to provide and optimize our services, prevent fraud, and create personalized recommendations."

This sentence is technically clear, but it's also essentially unlimited in scope. It doesn't specify which data, how it will be used, or what the actual limits are. It's consent, but it's not informed consent.

The Consent vs. Intent Problem

There's a fundamental mismatch between what people think they're consenting to and what they're actually consenting to. When someone signs up for Bilt to pay their rent and earn rewards, they think they're consenting to let Bilt handle rent payments and track their rewards spending.

What they're actually consenting to is a much broader set of practices:

- Method Financial accessing their credit bureaus

- Card networks sharing their card information

- Card issuers providing their account data

- Bilt aggregating all this information and maintaining it in their system

- Bilt sharing anonymized insights with merchant partners

- Bilt potentially adjusting rewards eligibility based on their financial profile

- Possible future uses of this data if Bilt is acquired or pivots their business

Most people don't understand the full scope of what they're signing up for. And companies know this. It's why the consent wall exists—it provides legal protection even though it doesn't actually result in informed consent.

What the Terms Actually Say

Let's break down what the actual terms and conditions typically authorize:

Data Collection: The app or service can collect your information through any means necessary, including third-party data sources. This is broadly written to cover both direct collection (when you enter information) and indirect collection (when aggregators pull your data).

Data Usage: The app or service can use your data for essentially any purpose that falls under their business operations. This includes service delivery, product optimization, fraud prevention, marketing, and creating insights. The language is broad enough to cover purposes that weren't even contemplated when you signed up.

Data Sharing: The app or service can share your data with "service providers" and "affiliated companies" and sometimes with "third parties for marketing purposes." Service providers is broadly defined to include almost any vendor they work with. Affiliated companies includes current and future subsidiaries. Third parties might include merchants, marketers, or analytics companies.

No Real Opt-Out: While terms often mention that you can contact customer service to opt-out of certain practices, the core data access (the credit bureau queries, the card network pulls) happens at the moment you sign up. By the time you might want to opt-out, your data has already been accessed.

The system is designed to make opting-in automatic and opting-out manual and difficult.

Most users spend about 30 seconds skimming terms, while a full read requires approximately 73 minutes. This highlights a significant gap in understanding.

Real-World Privacy Implications: What Actually Happens With Your Data

Okay, so companies can legally access your credit card information. But what actually happens with it? This is where the theory meets the reality of how your financial data is being used.

The Aggregation Economy

Once Bilt (or any platform) has your card information, they have something valuable: a complete picture of your financial wallet. They know:

- How many credit cards you have (signal of financial sophistication and access to credit)

- What types of cards you have (premium rewards cards indicate high income and spending)

- Which banks issued your cards (reveals your banking relationships)

- When your cards were opened (shows credit history length and acquisition patterns)

This information alone is valuable for targeting and personalization. But it becomes even more valuable when combined with other data points that these companies collect:

- Your location (where you live and work)

- Your transaction history (what you buy and where)

- Your demographic information (age, income, family status)

- Your behavior on their platform (how you use their services)

When you combine all of this, the platform has a remarkably detailed profile of who you are as a consumer. They know your financial capacity, your spending patterns, your credit quality, and your lifestyle.

Merchant Targeting and Local Optimization

Bilt specifically mentions that they share "anonymized preferences" at an "aggregate building level" with merchant partners. What does this actually mean?

It means that the coffee shop partner in your building can learn from Bilt that residents in this building spend 23% more on coffee than the average for the city. The local restaurant can learn that building residents skew toward higher-income demographics and are willing to pay premium prices. The gym can learn that residents in this building are particularly interested in fitness offerings.

This is sold to merchants as useful market intelligence. And it is useful. But it's also deeply personal aggregate information derived from individuals who mostly don't understand how their data is being used.

For the companies doing this, it's perfect. They get detailed local market insights that would otherwise cost thousands of dollars to acquire through market research. For the residents? They get slightly more targeted marketing from local merchants.

The Behavioral Economics Angle

There's another, more subtle way your data is being used. Once these platforms have your card information and spending data, they can start making predictions about your behavior.

Machine learning models can predict:

- What percentage of your spending will happen at their merchant partners (vs. competing platforms)

- How likely you are to upgrade to premium services

- What your lifetime value will be as a customer

- What rewards will be most likely to drive your transaction volume

These predictions then feed back into how the platform treats you. If their model predicts you have high lifetime value, you might get targeted with premium rewards. If their model predicts you're likely to churn, you might get retention incentives. If their model predicts you'll never use a certain feature, you might never see it.

You're not just being tracked. You're being modeled. And the model directly influences what opportunities are shown to you.

The Consent Mechanics: How Companies Get Permission Without Permission

This might be the most important section because it explains how all of this happens with your "permission" when you never really understood what you were permitting.

There are several dark patterns built into how fintech companies present these data access features:

The Default Accept Pattern

When you sign up for most financial services, the card-linking feature is presented as the default option. "Link your cards to get personalized rewards" is often the first thing you see after account creation. The implication is that this is how the service works, and you're slightly opting out if you choose the bank transfer alternative.

This is the "default accept" dark pattern. Instead of asking "Do you want us to access your credit cards?" the platform says "Here's how we'll access your credit cards to give you the best experience." One is a permission request. The other is a statement of fact.

The Bundled Consent Problem

When you agree to the terms of service, you're not consenting to individual practices. You're consenting to a massive bundle that includes:

- The service itself

- Data collection practices

- Data usage practices

- Data sharing practices

- Future changes to these practices

If you want the service, you have to accept all of it. There's no granular control. You can't say "yes to the rent payment feature, but no to the credit bureau access." It's all or nothing.

This is fundamentally unfair because reasonable people might have different privacy preferences. Some people might be happy to have their data accessed for rewards optimization. Others might find it creepy. But both groups are forced to accept the same terms or get no service at all.

The Legitimacy Washing Through Language

Companies use specific language to make their data practices sound legitimate and normal:

- "We work with trusted partners" (Trust is irrelevant; it's about whether you've consented)

- "Your data is secure" (Security and consent are different things)

- "We never sell your personal data" (Selling vs. sharing with partners is a legal distinction, not a privacy distinction)

- "You maintain control of your data" (You do, after you've already consented to extensive access)

- "Data is anonymized at the aggregate level" (Individual-level data is still very personal)

Each of these statements might be technically true, but together they create an impression of privacy protection that doesn't match the actual practices.

The Friction Asymmetry

Signing up and consenting to data access is easy. A few clicks. Seconds of your time.

Revoking consent or opting out is deliberately made harder. You might have to:

- Find the settings buried three levels deep in the app

- Submit a support request and wait for a response

- Verify your identity in multiple ways

- Accept that some features will stop working

- Contact Method Financial (the aggregator) instead of the app

The system is designed with asymmetric friction. Easy to opt-in. Hard to opt-out. This isn't accidental. It's intentional design.

Companies use financial data primarily for targeting and personalization (30%), followed by merchant targeting and local optimization (25% each). Demographic analysis accounts for 20%. Estimated data.

Practical Privacy Protection: What You Can Actually Do

Okay, you've read all of this and you're rightfully concerned. So what can you actually do about it? Here are concrete steps you can take starting today.

Option 1: Don't Link Your Cards

This is the nuclear option, but it's also the most effective. Most platforms that ask for card linking also offer alternatives:

- Bank account transfers: Transfer money from your checking account directly. Your bank account number is less sensitive than your full credit card data because you're not handing over your card brand, type, or history.

- Wire transfers: Slower but more private. Your information is just transmitted to the receiving account without intermediaries.

- ACH payments: Automated Clearing House payments work similarly to bank transfers and are widely supported.

You'll lose some optimization (Bilt won't be able to specifically match your transactions to rewards), but you'll keep your card information off distributed databases.

Option 2: Use a Limited-Purpose Card

If you want to use a platform but don't want to expose your complete card portfolio, consider getting a separate credit card specifically for that platform.

For example, if you're using Bilt to pay rent, get a rewards card specifically for rent payments and link only that card. The data aggregators will see one card instead of your complete financial wallet.

This doesn't solve the privacy problem entirely (they're still accessing your data), but it limits the scope of what they can see. The aggregators won't know about your other cards, your primary banking relationships, or your complete financial picture.

Option 3: Limit Your Platform Integrations

Every platform you connect to is another place where your data exists. Every integration is another set of terms and conditions you're agreeing to. The cumulative privacy impact of using many platforms is worse than the impact of using one.

Consider consolidating around a few trusted platforms rather than spreading your financial life across dozens of apps and services. If a company goes bankrupt, gets acquired, or changes their privacy practices, the damage will be limited to that one platform rather than distributed across many.

Option 4: Request Your Data

Under various state privacy laws (CCPA in California, CPRA, and similar laws in other states), you have the right to request the data that companies hold about you. This is extremely useful for understanding exactly what they know.

Send a data request email to the company's privacy contact (usually available in their privacy policy). Ask them to provide:

- All data they've collected about you

- All sources where they obtained that data

- All third parties they've shared your data with

- All uses they're making of your data

The response is often eye-opening. You'll see exactly what method financial has pulled from the credit bureaus, what the platform is inferring about you, and where your data is going.

Option 5: Opt Out of Data Broker Sharing

This one is tricky because there are thousands of data brokers, but you can take steps:

- Opt out of credit bureau sharing: Contact Equifax, Experian, and Trans Union and request to opt out of sharing your information with third parties (for prequalified offers). This reduces the number of inquiries coming your way.

- Use the National Do Not Call Registry: Register with the FTC's Do Not Call Registry to reduce marketing calls.

- Opt out of data brokers: Websites like Opt Out Prescreen.com and Privacy Rights.org have lists of data brokers you can contact directly.

Option 6: Freeze Your Credit

If you're extremely concerned about data access, you can place a security freeze on your credit with all three bureaus. This prevents anyone from accessing your credit report without your permission.

The downside is that you'll need to temporarily unfreeze whenever you want to apply for credit yourself. But it does reduce unauthorized access to your credit file by data aggregators and other third parties.

The Future: Where This Is All Heading

The fintech industry is still young, and the data practices we're seeing now are just the beginning. Here's what to watch for as this industry evolves.

Real-Time Financial Profiling

Current data aggregation happens at sign-up time. You link your cards, the system pulls your data, and it's mostly static (unless you actively update it).

The next evolution will be real-time profiling. Imagine platforms that continuously monitor your card data, transaction patterns, and financial changes. Not just seeing what cards you have, but seeing how your spending changes month to month, which merchants you frequent, and how your financial priorities shift.

This is technically possible with the current regulatory framework. All that's needed is continuous API access instead of one-time data pulls.

Predictive Financial Categorization

Once platforms have enough transaction and card data, they can start making detailed predictions about your behavior:

- How likely you are to take on more debt

- What types of products you're most likely to buy

- What your income level is (inferred from spending patterns)

- What your risk profile looks like (inferred from credit mix and payment history)

This isn't just valuable for optimizing rewards. It's valuable for credit decisions, insurance decisions, employment decisions, and marketing decisions.

Imagine if a landlord could request your Bilt profile and instantly see your complete financial picture. Or if a lender could make credit decisions based on your inferred behavior rather than your stated information. This is where the system could go.

Regulatory Pressure and Evolution

There's increasing pressure on regulators to update laws around data access. The FCRA is nearly 60 years old. Consumer protection agencies are starting to pay attention to data aggregation practices. State privacy laws are creating new requirements.

In the medium term, expect:

- Stricter consent requirements: More explicit, granular consent for different types of data usage

- Transparency mandates: Requirements for companies to disclose where data comes from and how it's used

- Opt-out provisions: Making it easier to revoke consent

- Data minimization: Requirements to collect only data that's necessary for specific purposes

But don't expect a fundamental shift away from data aggregation. The economic incentives are too strong, and the current regulatory framework still permits it.

The Open Banking and API Economy

One paradox is that the push toward "open banking" and financial data APIs might actually increase privacy concerns.

Open banking (like PSD2 in Europe and emerging systems in the US) is designed to give consumers access to their own financial data and the ability to share it with third parties. This is theoretically good for competition and consumer empowerment.

But in practice, it creates more friction for users to manage their data sharing. When there are hundreds of possible integration points and every integration requires consent, most people won't carefully manage them. They'll just accept broad permissions and forget about them.

We're likely heading toward a world where your financial data is shared across dozens of different platforms and APIs, making it effectively impossible to track or control where your information is going.

Estimated data shows that not linking cards is the most effective privacy protection strategy, followed by using a limited-purpose card and limiting platform integrations.

The Bigger Picture: Understanding the Incentive Structure

To understand why all of this is happening, you need to understand the incentives.

For fintech companies like Bilt, accessing customer financial data is valuable because it allows them to:

- Build better products (knowing exactly which rewards will appeal to each customer)

- Reduce risk (understanding their customers' financial capacity)

- Increase transaction volume (routing customers to partnered merchants)

- Create additional revenue streams (selling insights to merchants)

For data aggregators like Method Financial, providing access to this data is valuable because:

- Fintech companies pay for access to their aggregation services

- They can scale across dozens of clients with the same infrastructure

- Their business model requires them to have access to financial data

For credit bureaus and card networks, sharing data with aggregators is valuable because:

- It generates additional revenue from data access requests

- It creates relationships with emerging fintech companies

- It positions them as infrastructure for the digital finance economy

For card issuers, sharing data with platforms is valuable because:

- It drives transaction volume (and therefore merchant fees)

- It creates network effects (their cards become more useful)

- It differentiates their product

Everyone in the chain makes money. The only people who aren't explicitly compensated are you—the consumer whose financial data is being shared.

You get some value in the form of optimized rewards, personalized features, and convenient services. But whether that value exceeds the privacy cost is an entirely personal decision that each of us has to make for ourselves.

Protecting Yourself Proactively: A Comprehensive Strategy

If all of this has made you want to tighten down your financial privacy, here's a comprehensive strategy you can implement:

Monthly Privacy Audit

Once a month, spend 10 minutes reviewing:

- What platforms you've signed up for

- Which ones have access to your card data or bank accounts

- What you've actually used them for

- Whether they're still providing value

Delete or disconnect from anything that's not actively providing value. The fewer platforms that have access to your data, the smaller your overall exposure.

Annual Data Subject Access Request

Once a year, send data subject access requests to the major platforms you use. Request all data they have on you and all sources they obtained it from.

This serves two purposes:

- It lets you understand exactly what they know

- It creates a legal record that you've requested transparency, which can protect you in case of future disputes

Credit Monitoring and Lock

Check your credit reports at least once a year (available free at annualcreditreport.com). Consider placing a security freeze to limit unauthorized credit checks. Or at minimum, consider a fraud alert.

Selective Platform Use

Be intentional about which platforms you use and what you give them access to. Not every convenience is worth the privacy cost.

For rent payments specifically, consider:

- Paying directly from your bank account

- Using your building's payment system if they offer it

- Using a service that doesn't require card linking

You'll lose some rewards, but you'll keep your data safer.

FAQ

What is Method Financial and why do companies use it?

Method Financial is a data aggregation company that serves as an intermediary between consumers and financial data sources. They don't collect your data directly—instead, they have pre-established relationships with credit bureaus, card networks, and card issuers that allow them to query these systems on behalf of consumers. Companies like Bilt use Method Financial because it's easier than trying to establish relationships with dozens of data sources individually. Method Financial essentially acts as a consolidated bridge to the financial data ecosystem.

How do credit bureaus legally have information about all my credit cards?

Credit bureaus maintain financial information as a core function of their business. Credit card issuers, banks, and other financial institutions report account information to the bureaus so that credit decisions can be made consistently. This reporting is authorized by the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), which establishes that credit bureaus have a legitimate purpose to collect and maintain this information. When you apply for a credit card, you authorize the issuer to report to the bureaus. Over time, the bureaus build complete files on your credit accounts and payment history, which then becomes available for authorized queries.

Is it actually legal for companies to access my credit card information without asking first?

Technically yes, though with important caveats. Under the FCRA, companies are allowed to access your credit information for "permissible purposes" if you've consented. The catch is that consent is often buried in terms and conditions that most people don't read. You're technically consenting by signing up for the service, but this isn't informed consent in any meaningful sense. Some states have stronger privacy laws (like California's CCPA) that require more explicit consent for certain uses, but the baseline federal law permits this practice.

What happens to my financial data after a company collects it?

Companies can use your data for purposes described in their privacy policy, which typically include service delivery, fraud prevention, product optimization, and marketing. They can also share it with "service providers" (vendors they work with) and sometimes with "affiliated companies" or "third parties." Most platforms claim not to "sell" your data, but sharing it with partners for business purposes is essentially the same thing functionally. The data typically remains in their systems indefinitely unless you specifically request deletion.

Can I prevent companies from accessing my credit information?

Yes, several options exist. You can refuse to link your cards and use bank transfers instead. You can place a security freeze on your credit, which prevents most unauthorized access. You can contact the credit bureaus to request that they limit sharing of your information. You can opt out of prequalified offer sharing through Opt Out Prescreen.com. Or you can simply choose not to use platforms that require card linking. The most effective option is avoiding the platforms entirely, but you sacrifice the convenience and rewards they offer.

How do I know what financial data companies have collected about me?

You have the right to request your data under most state privacy laws and under the general principles of the FCRA. You can request your credit report free from annualcreditreport.com. You can send a formal data subject access request to any company asking them to provide all data they have on you and the sources they obtained it from. For credit bureaus specifically, you can request a "credit bureau dispute" if you believe the information is inaccurate. These requests can take 30-45 days to fulfill, but they're legally required.

Will opting out of card linking prevent all financial data access?

No, not completely. If you've been issued credit cards, your information exists in the credit bureaus regardless of whether you link them to any specific platform. Credit bureaus maintain your data as a core part of their business. However, opting out of card linking prevents a specific platform from accessing your card information through data aggregators. It doesn't prevent the data brokers from having your information or selling access to others—it just prevents that particular company from seeing it. For more complete protection, you'd need to place a security freeze on your credit.

How is Bilt different from other financial apps in terms of privacy?

Bilt isn't necessarily unique in accessing card data—many fintech companies do this. What made Bilt notable was how prominent and obvious they made the card-linking feature. Most platforms bury this in settings. Bilt put it front and center after signup. This made the normally invisible data access very visible, which is why it sparked privacy concerns. In terms of actual practices, Bilt is probably similar to many other platforms, but they were less willing to keep the data access hidden.

Conclusion: The Privacy Reckoning Is Coming

We've covered a lot of ground here. From the mechanics of how data aggregators work to the legal framework that permits all of this, from the incentive structures that drive data sharing to the practical steps you can take to protect yourself.

But the core truth remains: your financial privacy in America is profoundly compromised. Not because of hacking or corporate malfeasance, but because we've collectively built a system that treats financial data as a commodity to be traded rather than as sensitive information to be protected.

The infrastructure that allows Bilt to show you all your credit cards in seconds is the same infrastructure that allows thousands of companies to track, profile, and predict your financial behavior. It's a system designed for efficiency and profit, not for privacy.

What's particularly frustrating is that this system exists with your permission. You "agreed" to it by clicking through terms of service. You consented to it, even though you almost certainly don't understand what you consented to. The system works because it exploits the gap between actual consent and informed consent.

The good news is that there are signs of change. Regulators are paying attention. State privacy laws are starting to create new requirements. Consumer awareness is increasing. Companies are starting to realize that privacy breaches and data misuse carry real reputational costs.

But meaningful change will take time. The current system is too profitable for too many companies to be disrupted quickly. The incentives are aligned toward greater data collection and sharing, not less.

In the meantime, you have choices. You can choose which platforms to use and which to avoid. You can choose whether to link your cards or pay from your bank account. You can choose to be aware of what you're consenting to and make intentional decisions about your data.

It's not a perfect solution. You can't completely opt out of a financial system that's built on data sharing. But you can reduce your exposure. You can become harder to profile. You can make it slightly more expensive for companies to know everything about you.

And maybe, in aggregate, if enough people make intentional privacy choices, the incentives will shift. Maybe companies will realize they need to offer real privacy protection to compete. Maybe regulators will update laws to reflect how financial data actually works in 2025.

But that change starts with individuals understanding the system and making conscious decisions about their participation in it. Which is exactly what this article has been designed to help you do.

Key Takeaways

- Data aggregators like Method Financial access your credit card information through credit bureaus, card networks, and issuers with your technical consent buried in terms of service

- The Fair Credit Reporting Act permits this data access for broadly-defined "permissible purposes" that have expanded far beyond the 1970s intent

- You can protect yourself by refusing to link cards, using bank account transfers, checking your credit report annually, or placing a security freeze

- The system creates perverse incentives where opting in is easy and default, while opting out is deliberately difficult

- Meaningful regulatory change is coming but slow, so proactive personal privacy protection is essential now

![How Companies Know Your Credit Cards: Data Privacy Explained [2025]](https://runable.blog/blog/how-companies-know-your-credit-cards-data-privacy-explained-/image-1-1765657845143.jpg)