The Invisible Forces That Silence Us

Every day, millions of people bite their tongues. You might do it at work when you disagree with your boss. You do it on social media when you're afraid of public backlash. You do it in conversations when you worry about offending someone. Self-censorship isn't always dramatic or oppressive. Sometimes it's just... quiet.

But silence compounds. Individual moments of restraint stack up into cultural patterns. And cultural patterns create the conditions where authoritarianism takes root.

That's what makes recent research so important. Scientists at Arizona State University and other institutions have developed the first sophisticated computational models of how people decide whether to speak out or stay silent, and how those individual choices shape entire populations' relationship with freedom.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reveals something both unsettling and hopeful. Authoritarianism doesn't arrive overnight as a fully formed oppressive machine. It creeps in gradually through small restrictions, testing how much the population will tolerate. And the single most effective resistance? Boldness.

Not recklessness. Not naive optimism. But deliberate, sustained willingness to speak up despite consequences.

This research matters now more than ever. We're watching governments worldwide experiment with surveillance technologies, facial recognition systems, and content moderation algorithms. We're seeing social media platforms make wildly different choices about what to allow and what to suppress. We're experiencing the blur between public and private speech that the internet created. Understanding the science of silence and boldness gives us a clearer picture of what's happening and what we can do about it.

Let's dig into why people choose silence, how that silence gets weaponized, and what the research says about resisting these forces.

TL; DR

- Self-censorship is strategic: People rationally weigh the risks of speaking out against the costs of silence

- Boldness disrupts authoritarian creep: Populations that resist self-censorship prevent authorities from tightening control

- Punishment severity matters less than consistency: How authorities enforce rules shapes behavior more than how harsh those rules are

- Different systems take different approaches: Russia uses explicit rules, China uses ambiguity, and the US lets private companies decide

- Bottom line: Individual choices about speaking up have measurable, population-level effects on freedom

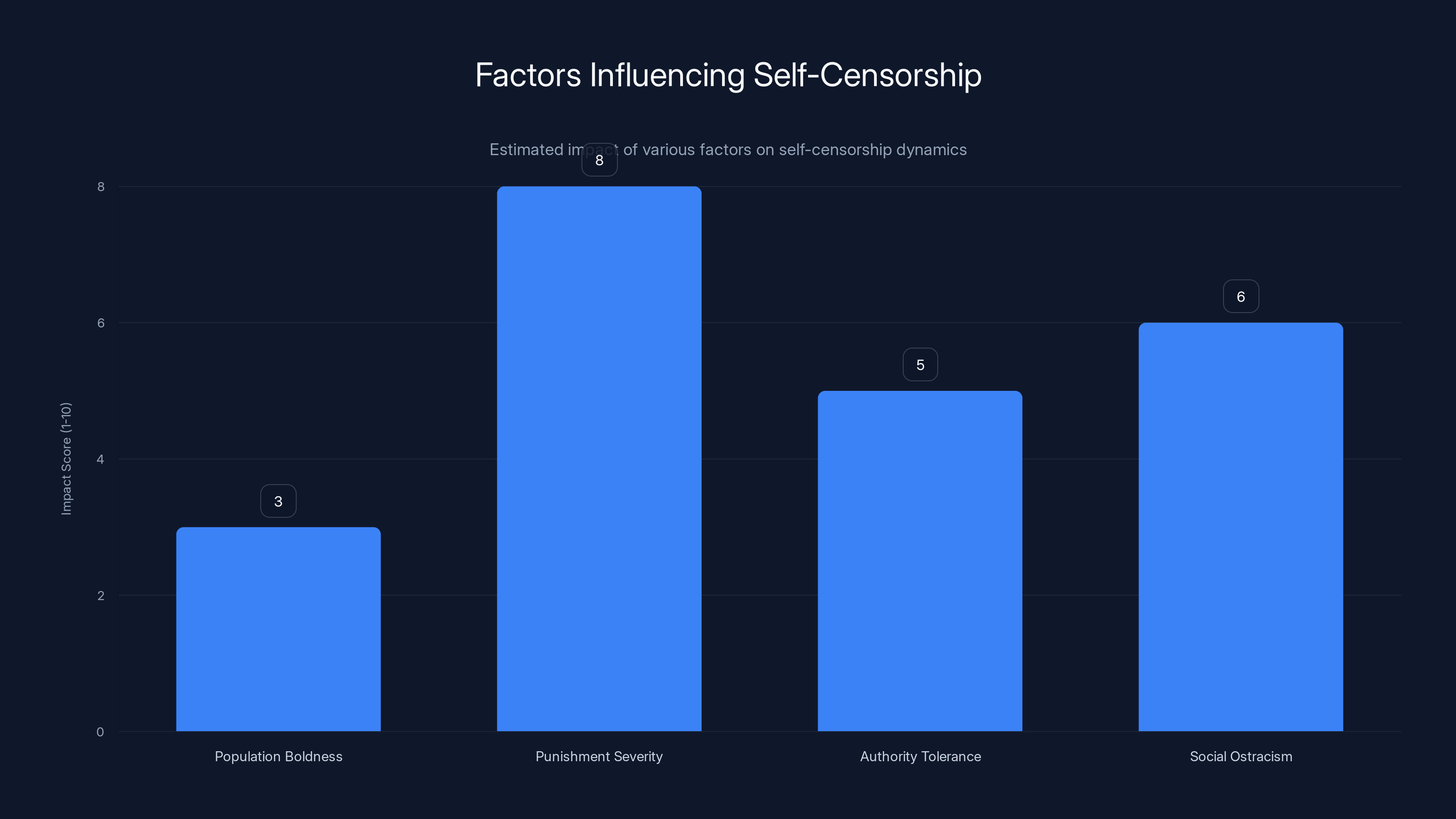

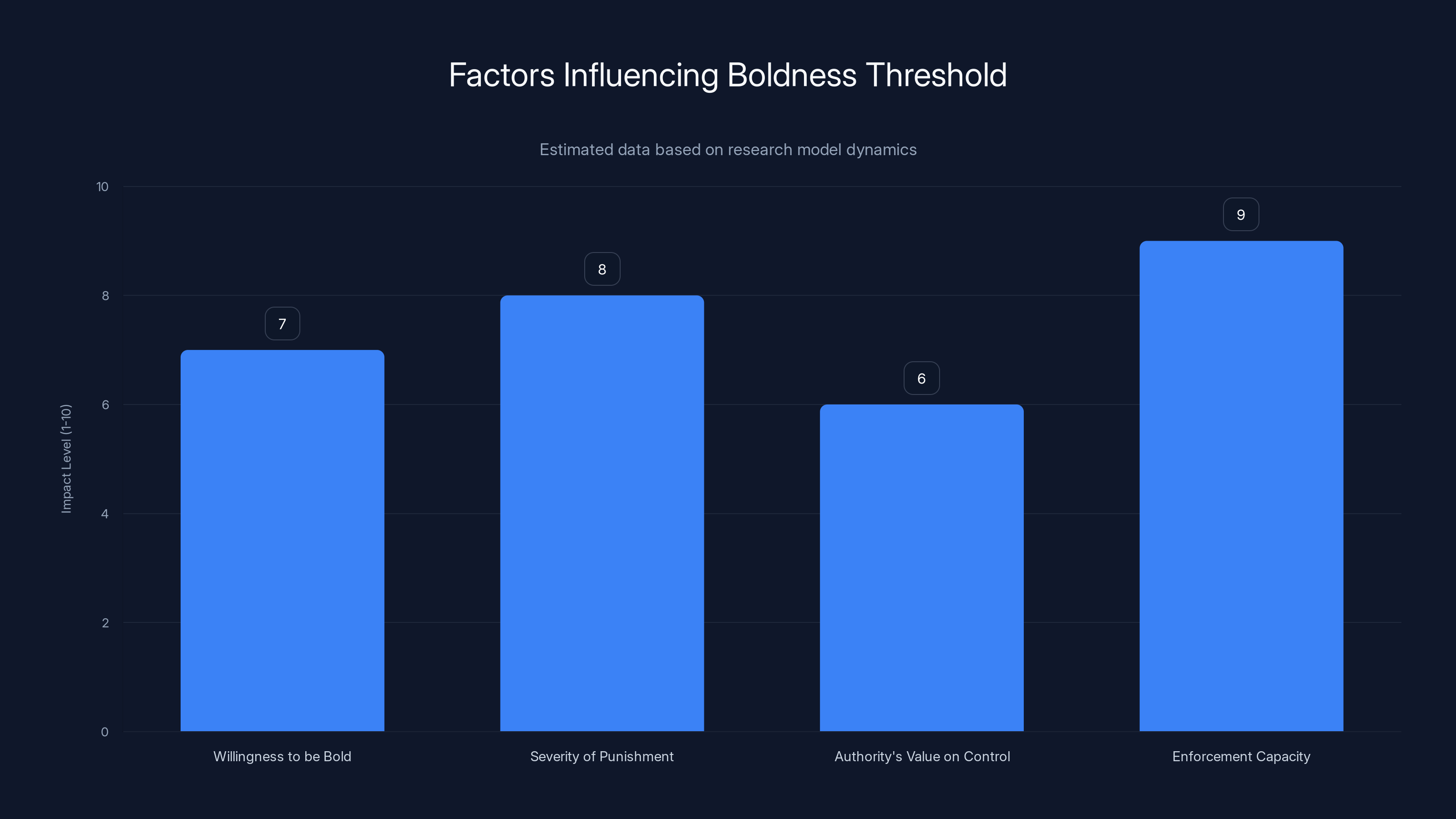

Estimated data shows punishment severity has the highest impact on self-censorship, while population boldness can mitigate its effects.

Why We Self-Censor: The Rational Calculation

Self-censorship isn't a character flaw or a sign of cowardice. It's a rational response to perceived risk.

Imagine you're at a company meeting. Your boss proposes a strategy you think is flawed. Speaking up might expose the flaw and make you look insightful. Or it might make you look like you don't trust leadership. You might get overlooked for the next promotion. The cost is uncertain but real.

Now imagine a more extreme scenario. You live in a country where publicly criticizing the government leads to arrest. The cost is no longer just professional disappointment. It's your freedom.

In both cases, your brain does the same calculation. Benefit of speaking minus cost of speaking. If the cost exceeds the benefit, you stay quiet.

The research team built a computational model that captures this calculation. They weren't trying to predict what any individual person would do in any specific situation. Instead, they modeled the broad behavioral patterns that emerge when thousands of people make similar cost-benefit decisions.

"We didn't go out and ask 1000 people what they would do," explained Joshua Daymude, one of the study's authors. "Our model allows us to embed assumptions about how people behave broadly, then lets us explore parameters. What happens if you're more or less bold? What happens if punishments are more or less severe? An authority is more or less tolerant?"

This approach is powerful because it lets researchers play with variables and predict outcomes. What happens if punishment severity increases by 20%? How does the population respond? What if boldness doubles? How does that change the equilibrium?

The answers surprised the research team.

The Asymmetrical Power of Boldness

The most counterintuitive finding involves the interplay between authority severity and population boldness.

Logically, if an authority simply cracks down extremely hard on all dissent, it should suppress it completely. Everyone's strategic choice becomes to say nothing. Problem solved for the authority, right?

But that's not how it works in the real world. Here's why: authorities don't have infinite resources. Suppressing all dissent completely requires detecting all dissent and punishing it consistently. That's expensive.

So most authorities don't start there. They start moderate. They test the waters. They gradually increase severity to see how much the population will tolerate before it pushes back.

This is where boldness becomes asymmetrically powerful. If a population is sufficiently bold, it doesn't cooperate with this gradual ratcheting of control. Every time the authority increases severity, the bold population still dissents. And the authority has to follow through with punishment, every single time.

That gets expensive fast. The authority either has to invest huge resources in enforcement, or back down.

But if a population starts self-censoring even at moderate authority levels, something different happens. The authority notices the reduced dissent and feels emboldened to increase severity a bit more. The population notices the increased severity and self-censors more. This feedback loop continues until the authority reaches total control without ever having to spend massive resources.

This is the "Hundred Flowers" phenomenon, named after Mao's famous campaign in 1950s China.

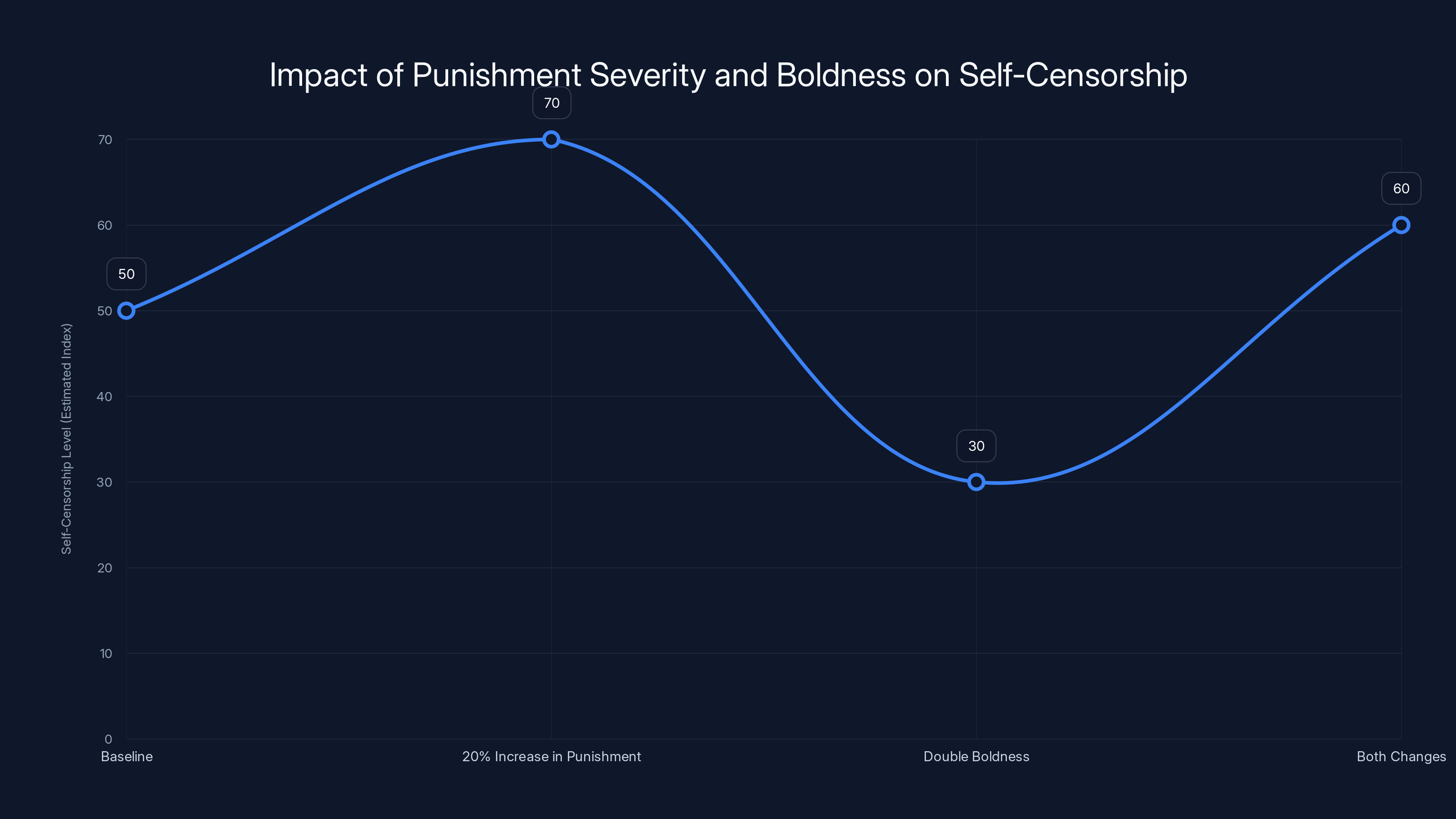

Estimated data shows that increasing punishment severity by 20% significantly raises self-censorship levels, while doubling boldness reduces it. The combination of both changes results in a moderate increase in self-censorship.

The Hundred Flowers Trap

Mao initially encouraged open criticism of the Chinese government. The strategy was ostensibly to invite feedback and identify problems. "Let a hundred flowers bloom," he said.

People took him at his word. Criticism poured in. And then, abruptly, Mao reversed course. The open season on criticism ended. Those who had spoken out were targeted. Intellectuals, artists, and political critics faced imprisonment and reeducation.

Why would Mao invite criticism only to punish it? The research model suggests an explanation: he was testing the population's willingness to dissent. Once he understood the baseline, he could calibrate his control strategy.

The model shows that this "flower bloom then crush" approach is devastatingly effective if the population cooperates by gradually increasing self-censorship. Each cycle of mild suppression leads to increased caution. Each time authority gets slightly harsher, people pull back a bit more. The feedback loop spirals until the population voluntarily censors itself completely.

But there's an escape hatch. If the population had been sufficiently bold from the start, this strategy fails. If citizens continued speaking out even after facing punishment, the authority would be forced to either escalate enforcement dramatically (expensive) or tolerate dissent.

This is why Daymude's key insight matters so much: "Be bold. It is the thing that slows down authoritarian creep. Even if you can't hold out forever, you buy a lot more time than you would expect."

Boldness acts like a circuit breaker. It disrupts the feedback loop that otherwise leads inexorably toward total control.

How Different Authorities Approach Suppression

Authoritarian governments don't have a one-size-fits-all strategy. Different countries experiment with different approaches.

Russia, particularly in recent decades, favors explicit rules. The government publishes lists of prohibited content and behaviors. If you violate any of the enumerated rules, authorities can punish you using existing laws. It's legalistic and specific. You know exactly what you can't do.

China takes the opposite approach. The government deliberately refuses to specify clear rules. It announces that citizens should "behave themselves" without explaining what that means. This ambiguity creates what one researcher called "The Anaconda in the Chandelier." You know there's a predator somewhere in the room, but you don't know exactly where or when it will strike. That uncertainty generates preemptive self-censorship. People police their own speech because they're terrified of accidentally crossing an invisible line.

The United States has taken a different path. Rather than direct government suppression, the US has largely outsourced content moderation to private tech companies. Platforms like Facebook, Twitter (now X), YouTube, and TikTok make their own rules about what's allowed. Some are permissive. Others are restrictive. There's no unified national policy.

Weibo, China's Twitter equivalent, has adopted a strategy closer to Russia's legalistic approach with Chinese characteristics. The platform publicly releases the IP addresses of users who post "objectionable commentary." This creates a different kind of fear. It's not abstract bureaucratic punishment. It's public exposure and potential mob harassment.

The research team observed these different approaches and realized something important: they're all experiments. Countries are testing what works.

The Role of Surveillance Technologies

Classically, suppressing dissent required finding dissidents and punishing them. That was expensive and difficult. You needed informants, secret police, detention facilities.

Modern surveillance technologies change the economics dramatically.

Facial recognition systems can identify protesters from surveillance footage. Digital monitoring can track which websites people visit and what they search for. Social media algorithms can surface dissidents' names and locations. AI-powered content moderation can flag banned speech automatically. Geofencing can identify who attended a political gathering.

Each of these technologies is sold as a neutral tool. Facial recognition helps find criminals. Content moderation prevents harmful speech. Surveillance catches dangerous terrorists.

But in the hands of authoritarian governments, these tools become instruments of suppression. And they fundamentally change the calculations people make about whether to speak out.

If you know facial recognition will identify you in a crowd of protesters, you're less likely to attend. If you know algorithms track your search queries, you're less likely to research sensitive topics. If you know your social media posts might trigger automated detection, you self-censor.

The research model doesn't explicitly incorporate these technologies, but their effect is clear: they lower the cost of enforcement for authorities. And lower enforcement costs mean authorities can maintain control with less severity.

This is where private tech companies become crucial decision-makers. When a platform decides to implement strong content moderation, it's making a choice about how much surveillance to conduct and how much to cooperate with government requests. When it refuses, it's making a different choice.

These corporate decisions shape the environment in which citizens make their own choices about speaking out.

Estimated data shows that a bold population maintains higher dissent levels even as authority severity increases, while a self-censoring population decreases dissent significantly.

When Self-Censorship Is Actually Healthy

The research team was careful to note that self-censorship isn't always bad.

Daymude pointed out that the mathematical model is general enough to apply to many situations beyond oppressive regimes versus freedom-loving people. "Self-censorship is not always a bad thing," he said. "This is a very general mathematical model that could be applicable to lots of different situations, including discouraging undesirable behavior."

Consider social norms around traffic laws. Speed limits are a form of enforced rule-setting. Most people comply without being caught and punished every time. They self-censor their desire to drive fast because they've internalized that excessive speed endangers others.

Or consider workplace norms around professionalism. You probably don't say every thought that crosses your mind in a meeting. You self-censor because you understand that certain comments would be unprofessional or hurtful.

The question isn't whether self-censorship exists. It's whether the rules being enforced serve legitimate collective purposes or whether they're being used to consolidate power and suppress dissent.

That distinction matters enormously. Self-censorship in service of reasonable social norms supports functioning communities. Self-censorship enforced through fear of political punishment undermines them.

The Punishment Strategy That Works Best

The research examined two different punishment approaches: uniform and proportional.

Uniform punishment means any violation of the rule, no matter how minor, results in the same consequence. You speed one mile over the limit? Same ticket as if you'd been doing 20 over. You make a mild criticism of the government? Same punishment as if you'd made a severe one.

Proportional punishment means the consequence matches the severity of the violation. Minor speeding gets a warning. Serious speeding gets a larger fine. Mild criticism gets a conversation. Serious sedition gets detention.

You might expect uniform punishment to be more effective as a deterrent. It's harsher and more final. But the model suggests otherwise.

Uniform punishment is actually less efficient at suppressing dissent because it doesn't give people a gradient of risk. Once you've crossed the line even slightly, you might as well cross it significantly. The punishment is the same.

Proportional punishment works better because it allows people to find a middle ground. You can express mild disagreement and face mild consequences, or you can stay completely silent and face none. This gives people room to exist in a safer zone while still allowing some voices to be heard.

This finding has real-world implications. If an authority wants to suppress dissent while minimizing resistance, proportional punishment is actually more effective than draconian uniform punishment. It's insidious in its moderation.

It also explains why some oppressive systems seem almost merciful compared to others, yet are often more successful at controlling populations. They're not being merciful out of the goodness of their hearts. They're being strategic.

The Social Media Complication

Social media has transformed the landscape of speech and censorship in fundamental ways.

Traditionally, public speech and private speech were distinct. You could say things in private to friends and family that you'd never say publicly. The barriers to public speech were high. You needed access to media infrastructure, which only a few people had.

Social media demolished those barriers. Now anyone with a smartphone can broadcast to millions. Private speech and public speech have blurred into a strange middle ground.

This creates confusion about what counts as dissent. Is a private message to friends dissent? What about a post on a closed group? What about a public tweet?

Authoritarian governments are still figuring this out. China's approach of refusing to clearly define boundaries works reasonably well when speech channels are controlled and relatively centralized. But on social media, there are infinite possible contexts and audiences.

Companies are experimenting with different solutions. Some, like Twitter under Elon Musk, have moved toward minimal moderation. Others, like TikTok, face intense government pressure to moderate aggressively. WeChat operates under Chinese surveillance. Facebook makes its own policies.

These different approaches create a fragmented landscape where the risk of speaking out varies drastically depending on which platform you're using. That itself becomes a form of control. People migrate toward platforms with less moderation, but they understand those platforms might face pressure from governments to increase moderation.

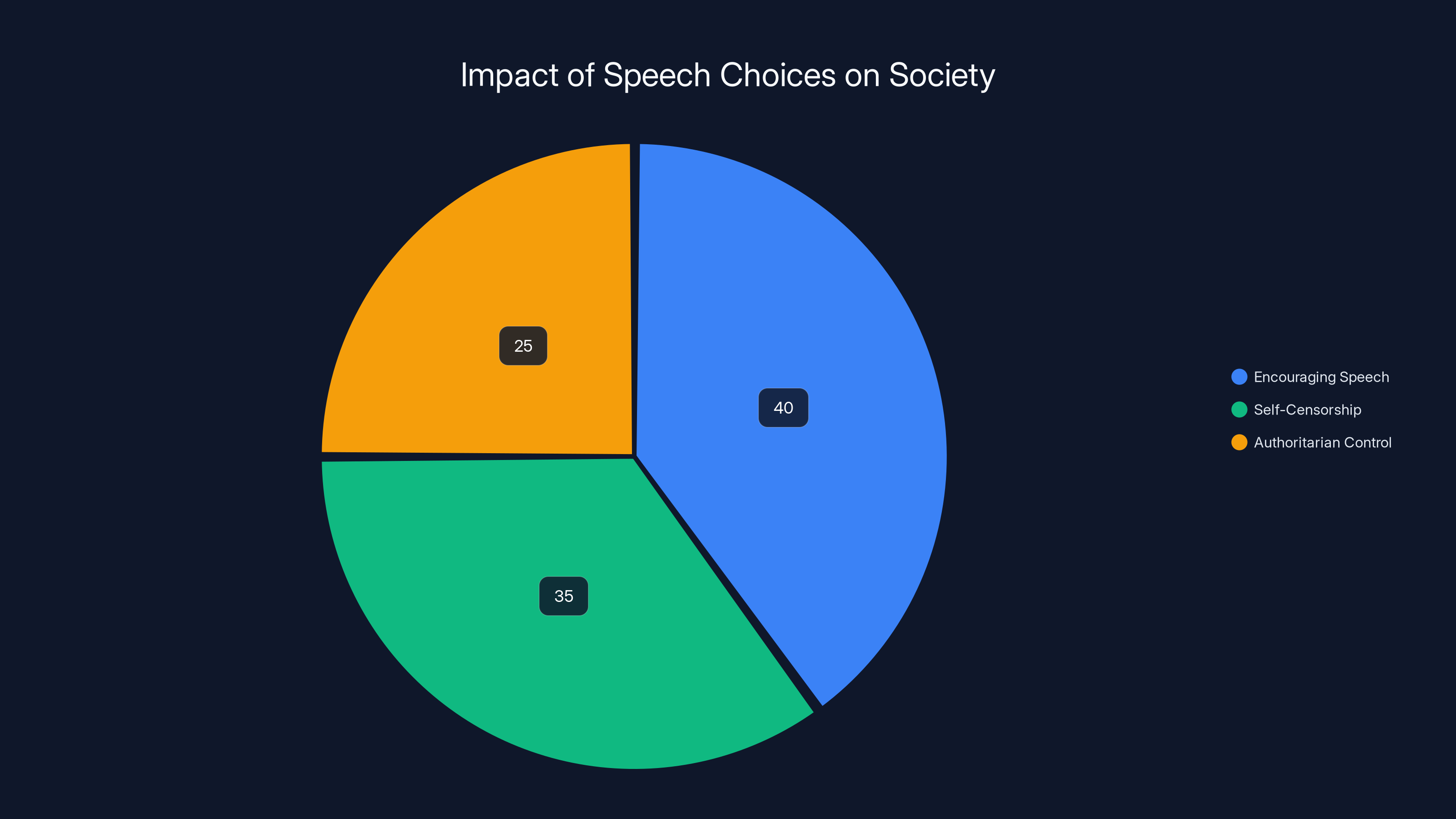

Estimated data shows that encouraging speech has the largest positive impact on society, while self-censorship and authoritarian control contribute to negative outcomes.

Boldness as Rational Strategy

The research reframes boldness as something other than reckless heroism.

Boldness, in the model's terms, is a strategic choice. Bold people are those who continue to dissent even when facing moderate punishment costs. They don't do this out of principle necessarily. They do it because they understand the equilibrium. They recognize that if everyone self-censors, the authority escalates. If enough people resist, the authority's hand is forced.

This transforms boldness from an individual virtue into a collective strategy.

Consider a protest movement. If most people stay home out of fear, the protest fails and authorities feel emboldened to increase restrictions. But if a critical mass of people show up despite knowing there might be consequences, several things happen. The protest's size becomes visible and harder to suppress. The authorities' hand is forced. And other people, seeing the resistance, gain courage to join.

The research model captures this dynamic. There's a threshold of boldness. Below it, the authority's strategy of gradual escalation works. Above it, the authority loses control.

What's the threshold? The model suggests it depends on several factors: how bold people are willing to be, how severe the current punishment is, how much the authority values control, and how much the authority can afford to enforce.

In mature democracies with strong legal protections, the boldness threshold is lower. People can speak out without fear of serious consequences, so the authority has to tolerate more dissent.

In authoritarian states with weak protections and high enforcement capacity, the threshold is higher. People need to be quite bold to resist, and it takes critical mass.

The Network Effects of Silence and Speech

One aspect the research highlighted is the feedback loop between individual choices and population-level effects.

When you decide to self-censor, you're making an individual choice based on your assessment of risk. But that choice also influences what others see and what other people believe about the level of risk.

If you see your friends staying silent on social media, you might assume the risk is high. You self-censor too. If you see them speaking out, you might feel braver.

This creates powerful amplification effects. Self-censorship can become self-perpetuating. Speech can become self-perpetuating.

During the early stages of social movements, this dynamic is crucial. The first people to speak out take the most risk because they don't know if others will join them. They're making a leap of faith.

But if their speech isn't suppressed, or if they gain support, others feel emboldened. Each additional voice makes it harder for authorities to suppress everyone. This is why the first voice is so important. It's not just one person speaking. It's the first crack in the wall of silence.

Conversely, when authorities successfully suppress the first voices, it sends a chilling message to everyone else. The silence deepens.

What the Model Reveals About Digital Platforms

The research team developed the model partly to understand why different social media platforms make such different moderation choices.

On the surface, this seems irrational. Facebook and Twitter are similar platforms with similar business models. Why would they make opposite choices about moderation?

The research suggests one possibility: they're responding to different regulatory and cultural pressures. In Europe, with its strong privacy regulations and skepticism of unchecked corporate power, platforms face pressure to moderate aggressively. In the US, the regulatory environment is lighter, so some platforms can afford to moderate less.

But there might be another factor at play. Different moderation strategies might reflect different assumptions about what level of dissent the platform's host country will tolerate.

A platform that operates in a country with a strict government might adopt aggressive moderation to avoid triggering government crackdowns. A platform operating in a more permissive environment can afford to moderate less.

This means the platforms themselves, through their moderation choices, are shaping the environment in which users decide whether to speak. They're effectively changing the cost of dissent.

When a platform removes your post without explaining why, you experience that as an arbitrary punishment. It changes your assessment of the risk. Next time, you self-censor more.

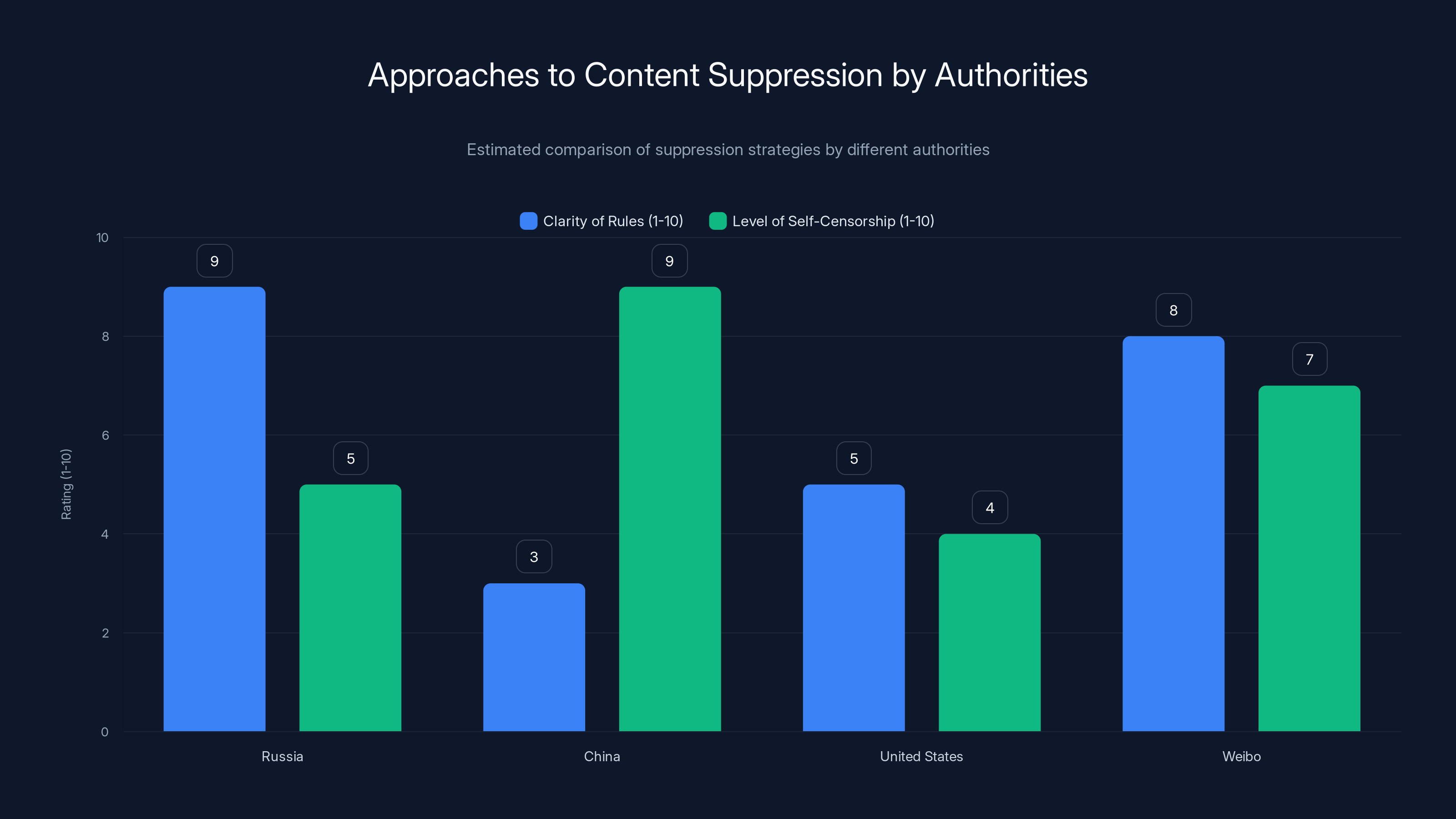

Estimated data shows Russia and Weibo have clearer rules, while China has higher self-censorship due to ambiguity. The US has moderate clarity and self-censorship levels.

The Economics of Enforcement

Underlying all of this is an economic calculation. Suppressing dissent costs money and attention.

Authorities have to invest in surveillance infrastructure, punishment mechanisms, and monitoring systems. They have to allocate personnel to identify and punish dissenters. All of this has a budget.

The research model captures this by allowing authorities to choose different enforcement levels. An authority can be very strict and expensive, catching nearly all dissent. Or it can be moderate and cheaper, letting some dissent through.

What the research reveals is that moderate enforcement combined with population self-censorship is often more economically efficient than draconian enforcement.

This is darkly clever. An authority that wants to suppress dissent on a budget should adopt moderate punishments and let the fear of those moderate punishments cause people to self-censor. That requires less expensive enforcement than trying to catch and punish everyone.

It also explains why genuinely oppressive systems often don't look like cartoon villains. They often look relatively normal on the surface. The oppression works through fear and internalized caution rather than visible violence.

This matters because it makes authoritarianism harder to recognize and resist. When oppression is visible and brutal, people mobilize against it. When it's subtle and people police themselves, resistance is harder to organize.

Case Studies: Real-World Applications

The research team pointed to several real-world examples that fit their model.

China's approach exemplifies the "ambiguous punishment" strategy. The government doesn't publish detailed rules about what speech is forbidden. Instead, it makes vague statements about what's acceptable and lets citizens figure it out. This generates preemptive self-censorship because people don't want to accidentally cross an invisible line.

Russia's approach is more legalistic. The government publishes rules about what's forbidden, then punishes violations. This is more transparent but also more rigid.

The United States occupies a middle ground, with private platforms making moderation decisions rather than the government making them directly. This has created an inconsistent landscape where risk varies by platform.

Historically, the Hundred Flowers campaign in 1950s China is perhaps the most dramatic example of the Hundred Flowers trap the model describes. By inviting criticism and then crushing it, Mao didn't just punish dissenters. He demonstrated that even an explicit invitation to speak could lead to punishment. That broke people's trust and increased self-censorship going forward.

More recently, we've seen similar dynamics play out on social media. When platforms make arbitrary moderation decisions or when governments pressure platforms to remove content, it chills speech. People don't know what the actual rules are, so they self-censor preemptively.

The Time Dimension: Why Bold Populations Get More Time

One of the more fascinating findings involves timing.

The model shows that a bold population doesn't permanently prevent authoritarian creep. Eventually, if the authority persists and resources permit, it can still suppress dissent through sustained effort.

But boldness buys time. Sometimes a lot of it.

Why? Because every time a bold population resists, the authority faces a choice: escalate enforcement at greater cost, or back down. If the authority consistently backs down, it signals weakness and encourages more resistance. If it escalates, it's spending more resources.

Meanwhile, circumstances can change. A government official retires or dies. Political coalitions shift. Economic crises force budget cuts. International pressure increases. Public attention focuses elsewhere.

The longer the period of time where a population resists suppression, the more likely some of these circumstances will change. A bold population might not prevent authoritarianism permanently, but it might prevent it from consolidating before external circumstances change.

This has huge implications for how we think about resistance to oppression. You don't have to permanently defeat authoritarianism. You just have to delay it long enough that something else changes.

Historically, this has happened numerous times. Governments that seemed destined for permanent control collapsed. Sometimes it was economic pressure. Sometimes it was international intervention. Sometimes internal dynamics shifted.

But those collapses were more likely when populations had maintained some capacity for dissent, rather than having been completely suppressed.

The boldness threshold is influenced by multiple factors, with enforcement capacity and severity of punishment having the highest impact. Estimated data based on model dynamics.

Technological Solutions and Their Limits

Some people propose technological solutions to the censorship problem. Encrypted messaging apps that authorities can't intercept. Distributed social networks that no government can control. Anonymous posting systems that protect users' identities.

These tools are genuinely useful. They can protect people in dangerous situations. They can make surveillance more difficult.

But they don't solve the fundamental problem the research highlights. Because the research shows that self-censorship isn't just about external punishment. It's about internalized fear.

Even with encrypted communication, you might not speak out because you're afraid of what people might do if they found out, or because you've internalized society's disapproval, or because you're genuinely uncertain whether the risk is worth it.

Technology can lower the cost of speaking, but it can't eliminate people's calculations about those costs. And if most people still self-censor, even with protected tools available, the tools don't solve the problem.

This suggests that the boldness the research emphasizes isn't primarily a technological problem. It's a social and psychological one. People need to believe that speaking out is worth the risk. They need to see others doing it successfully. They need to believe they'll face community support rather than isolation.

Tools can help enable this. But the real work happens in culture, community, and individual courage.

Why Authoritarianism Targets Speech First

The research paper doesn't explicitly answer this question, but it's implicit in the findings.

Authoritarians target freedom of speech before other freedoms for a strategic reason. Speech is the mechanism through which people coordinate resistance to other restrictions.

If you can control what people say, and what they see others saying, you can control what people believe is possible. You can make people think they're alone in their grievances. You can prevent coordination of collective action.

Suppressing speech isn't an end goal for authoritarian governments. It's a means to the end of maintaining power. By controlling the information environment, authorities can make other oppressive policies seem inevitable or acceptable.

This is why the research finding about boldness matters so much. If enough people refuse to self-censor, they maintain the ability to coordinate, to share information, to recognize that they're not alone.

Once that happens, authorities can't easily consolidate power, even if they want to. The speech constraint becomes the bottleneck.

The Future of Digital Speech

The research was conducted as tech companies were experimenting with different moderation approaches. Some platforms were getting more permissive. Others more restrictive.

That experimentation is continuing. New platforms emerge. Government pressure changes. Technologies evolve.

The research suggests that what happens next depends partly on choices that seem technical or corporate but are actually fundamentally political. When Elon Musk took over Twitter and promised to reduce moderation, he was making a choice about what kind of environment speech would occur in. When other platforms tighten moderation, they're making the opposite choice.

These aren't just platform policies. They're shaping the environment in which people decide whether to speak. They're literally changing the cost of dissent.

The research also suggests that different regions might head in different directions. Some places might become more permissive as people demand less censorship. Others might become more restrictive as governments assert control.

The divergence might not stabilize. Instead, we might see increasingly polarized ecosystems where some people live in heavily moderated information environments and others live in loosely moderated ones.

That fragmentation creates its own problems. Different populations might develop incompatible understandings of reality. Coordination becomes harder. But it also might make total control harder, because no single authority controls all the information.

Individual Agency in Collective Dynamics

One of the most important takeaways from the research is that individual choices matter.

You might think that when facing a massive authority with surveillance, enforcement, and punishment capability, your individual choice to speak or stay silent doesn't matter. The authority is too big. The power imbalance is too large.

But the research shows this intuition is wrong. Individual choices aggregate into population-level effects. If enough individuals make the bold choice to speak, it changes the equilibrium. The authority can't suppress everyone. Its enforcement costs go up. Its control becomes less stable.

This doesn't mean individual boldness automatically wins. But it means that individual choices aren't meaningless. They're part of the calculation that determines outcomes.

Conversely, individual self-censorship also matters. If you stay silent, you're contributing to the silence that makes authorities' jobs easier. You're sending a signal to others that the risk is high and silence is common.

The research reframes the problem of authoritarianism from something that happens to people to something that people collectively create or prevent.

This is both empowering and sobering. It's empowering because it suggests that ordinary people have more agency than they might think. It's sobering because it means the responsibility for maintaining free speech falls partly on ordinary people, not just on institutions.

What Gets Lost When Speech Is Suppressed

Beyond the immediate question of whether a person gets punished, there's a deeper loss when speech is suppressed.

When people self-censor, they're holding back information, perspectives, and ideas. Some of that self-censorship protects genuinely harmful speech from spreading. But much of it suppresses valuable contributions.

The researcher who stays silent about a flaw in the government's policy might have had a solution. The activist who doesn't speak up might have energized others. The artist who self-censors might have created something beautiful and challenging.

Over time, suppressed speech means suppressed innovation, creativity, and problem-solving. Societies that successfully suppress dissent often find themselves stagnating culturally and economically.

This isn't just an abstract loss. It shows up in real outcomes. Countries with strong free speech protections tend to outcompete authoritarian countries in technology, arts, business innovation, and scientific advancement.

Part of the reason is that free speech enables the kind of creativity and risk-taking that drives innovation. When people are afraid to express new ideas, progress slows.

Building a Culture of Speech

What the research suggests is that maintaining freedom of speech isn't just about defending it against attacks. It's also about actively building a culture where speech is valued.

This means celebrating people who speak out, even when we disagree with them. It means supporting platforms and institutions that protect speech. It means teaching people that dissent is legitimate and valuable.

It means accepting that some speech will be uncomfortable or offensive, and that's part of the cost of freedom.

It also means being thoughtful about when and how to enforce consequences for speech. As the research noted, proportional punishment is more effective at maintaining control than severe punishments. But the inverse is also true. Disproportionate punishments for minor transgressions create a chilling effect without achieving much.

Building a culture of speech means calibrating enforcement toward genuinely harmful speech, not speech that's merely unpopular.

The Research's Limitations and Future Directions

The research team was clear that their model makes simplifying assumptions. They don't claim to predict exactly what any specific population will do in any specific situation.

Instead, they're modeling broad patterns. What happens to self-censorship as authority severity increases? How does population boldness change the dynamics? What's the equilibrium?

Future research might incorporate additional factors the current model doesn't fully capture. The role of media ecosystems and information spread. The impact of economic conditions on willingness to speak. The effects of different demographic groups having different risk tolerances.

The model also doesn't capture the role of leadership and coordinated action. Some people decide to speak not because they've independently calculated it's worth it, but because a leader they trust is also speaking. This herding behavior could be incorporated into future models.

Another area for future work is understanding how online platforms specifically affect these dynamics. The current research was developed as an explanatory framework, not as a tool to optimize platform moderation policies. But future work might use the model to predict how different moderation approaches would affect speech patterns.

There's also the question of how the research applies across different cultural contexts. The model assumes people make rational cost-benefit calculations about speech, but cultures vary in what counts as acceptable speech and what consequences are expected. Future research might explore cultural variations.

Practical Implications for Democratic Societies

If you live in a relatively free society, what does this research mean for you?

First, it suggests that the baseline freedom you enjoy isn't guaranteed. It depends partly on collective choices about whether to exercise speech rights. If everyone self-censors out of abundance of caution, even in the absence of severe external pressure, the space for speech shrinks.

Second, it suggests that defending free speech is partly an individual responsibility. Not everyone needs to be an activist or public figure. But maintaining a culture where people feel comfortable speaking up, disagreeing, and expressing dissent is important.

Third, it highlights the danger of "mission creep" in enforcement. An authority that starts with moderate suppression of genuinely harmful speech might gradually expand that suppression to include unpopular speech, then controversial speech, then any speech that challenges power.

The research suggests that the people who resist even moderate suppression, even when they might have legitimate concerns about the speech being suppressed, are doing something more important than defending that specific speech. They're defending the principle that authorities shouldn't be the sole judges of what can be said.

Fourth, it suggests that how we implement content moderation matters. Moderation that's proportional, transparent, and applied consistently is less likely to create a chilling effect than arbitrary moderation.

Fifth, it highlights the importance of plural media ecosystems. When many platforms exist and compete, no single authority controls the information environment. This makes total control harder.

Why Now Matters

The research was published at a time when surveillance technology is advancing rapidly, content moderation is becoming more sophisticated, and governments worldwide are testing different approaches to controlling speech.

Much of what the research describes is theoretical, based on mathematical models and historical examples. But the theories are being tested in real time.

We're watching China implement sophisticated facial recognition systems to monitor population movement. We're seeing countries pass laws requiring tech platforms to remove content or face penalties. We're seeing governments pressure platforms to suppress dissent. We're seeing platforms respond with different moderation strategies.

Each of these is an experiment in the dynamics the research describes. The outcomes will shape what's possible for speech in the future.

The research's message about boldness cuts against the current drift in many societies. The default strategy of many people is to stay quiet. The default strategy of many authorities is to gradually increase control. The research suggests that maintaining freedom of speech requires active resistance to that drift.

It doesn't require heroic sacrifice. It doesn't require that everyone becomes an activist. It requires that enough people refuse to self-censor, refuse to assume the worst, refuse to let fear completely determine their choices.

FAQ

What is self-censorship and why do people do it?

Self-censorship is the voluntary suppression of speech, beliefs, or ideas due to fear of negative consequences. People self-censor when they perceive that the cost of speaking outweighs the benefit, whether the cost is legal punishment, social ostracism, professional consequences, or other harms. It's a rational response to perceived risk, not necessarily a character flaw.

How does the research model self-censorship dynamics?

The researchers created a computational agent-based model that simulates how individuals balance their desire to speak with their fear of punishment. The model allows researchers to adjust variables like population boldness, punishment severity, and authority tolerance to explore how these factors interact. Rather than predicting individual behavior, the model reveals broad patterns in how self-censorship emerges and spreads through populations.

What is the "Hundred Flowers" trap described in the research?

The Hundred Flowers trap occurs when an authority initially permits or even invites dissent, then abruptly suppresses it. This teaches the population that even explicit permission to speak carries hidden risks. The model shows this is an effective way to gradually increase self-censorship because each cycle of moderate suppression makes people increasingly cautious. The name comes from Mao's campaign in 1950s China that followed exactly this pattern.

How does boldness help resist authoritarian control?

Boldness refers to the willingness to continue speaking or dissenting even when facing punishment costs. The research shows that if a population is sufficiently bold, it disrupts the authority's ability to gradually tighten control. Each time the authority increases severity, bold populations continue dissenting, forcing the authority to either escalate enforcement (expensive) or tolerate dissent. This creates a circuit breaker preventing the gradual feedback loop that otherwise leads to total control.

What's the difference between uniform and proportional punishment?

Uniform punishment applies the same consequence regardless of violation severity. Minor infractions receive the same penalty as major ones. Proportional punishment matches the consequence to the severity of the violation. The research shows proportional punishment is actually more effective at suppressing dissent because it allows people to find middle ground, self-censoring slightly rather than being forced to either stay silent completely or face the same harsh consequence regardless of degree.

How do different governments approach speech control?

Russia uses explicit rule-enumeration, publishing specific laws that define forbidden speech so people know what to avoid. China uses ambiguity, deliberately refusing to specify boundaries so people don't know where the line is, generating preemptive self-censorship. The United States outsources moderation to private companies. Weibo releases IP addresses of rule-breakers. Each approach has different costs and effectiveness for the authority.

Does technology make speech suppression easier or harder?

Modern surveillance technologies like facial recognition, content moderation algorithms, digital monitoring, and AI detection systems make it easier for authorities to detect and potentially suppress speech. These tools lower the enforcement costs for authorities, meaning they can maintain control with less severe punishments. However, encrypted communication tools and decentralized platforms can make suppression harder. Technology affects the balance but doesn't determine outcomes.

Is self-censorship always bad?

No. Self-censorship serves legitimate purposes in many contexts. Social norms around professionalism, safety, and respect involve elements of self-censorship. The question isn't whether self-censorship exists, but whether it serves legitimate collective purposes or whether it's being weaponized to consolidate power. Self-censorship enforced through fear of political punishment undermines democracies, while self-censorship in service of reasonable social norms supports functioning communities.

How does social media complicate speech dynamics?

Social media blurred the line between public and private speech. Anyone can broadcast to millions, but they're also visible to authorities and corporations in new ways. Different platforms make different moderation choices, creating an inconsistent landscape where risk varies by platform. This fragmentation makes it harder for authorities to maintain uniform control but also creates confusion about what speech is actually risky.

What can individuals do to maintain freedom of speech?

The research suggests that maintaining free speech isn't just about defending it institutionally but about building a culture where speech is valued. This means exercising free speech rights, supporting platforms and institutions that protect speech, celebrating dissent even when disagreeing, and resisting the urge to assume the worst about safe speech. It means accepting that uncomfortable or offensive speech is part of the cost of freedom, while still maintaining standards about genuinely harmful speech.

Conclusion: Speaking Into the Silence

The science of self-censorship reveals something that might seem obvious but becomes profound once you really understand it: your silence isn't just personal. It's political.

When you choose not to speak because you're afraid, you're contributing to an environment where others feel more afraid. You're sending a signal that the cost of dissent is high. You're making the authority's job easier by doing their work for them, policing your own speech before they have to.

But the inverse is also true. When you choose to speak despite the fear, when you refuse to self-censor preemptively, you're changing the environment for others. You're signaling that dissent is possible. You're forcing authorities to make an explicit choice about whether to suppress you, rather than letting them rely on everyone's internalized fear.

The research team's key finding sounds simple but runs counter to how most of us naturally respond to threats: "Be bold. It is the thing that slows down authoritarian creep."

Boldness isn't recklessness. It's not ignoring real risks. It's the calculated decision to speak despite those risks, understanding that doing so buys time, creates opportunity for things to change, and prevents the inexorable drift toward total control.

We're living in a moment where that's increasingly relevant. Surveillance technology is advancing. Content moderation is becoming more sophisticated. Governments worldwide are testing different approaches to controlling speech. Tech companies are experimenting with different moderation strategies.

Each of those experiments has winners and losers. The winners are the populations and companies that figure out how to maintain vibrant speech ecosystems. The losers are those that drift toward silence and control.

The research suggests the outcome isn't predetermined. It depends on choices. Choices by authorities about how severely to punish speech. Choices by platforms about how aggressively to moderate. And choices by individuals about whether to speak.

That's both empowering and sobering. It's empowering because it suggests ordinary people matter, that your choices have consequences beyond your own safety. It's sobering because it means responsibility for maintaining free speech falls on all of us, not just on institutions or leaders.

But that's also reason for hope. Because it means that change is possible. The population that seems silent and cowed can rediscover its voice. The authority that seems all-powerful can be thwarted by populations that refuse to cooperate with their own suppression. The platform that seems to have total control can be challenged by people choosing to speak elsewhere.

History is full of moments when speech reasserted itself. When people decided the cost of silence was higher than the cost of speaking. When populations realized they were stronger together than the authority was alone.

The next one of those moments might be closer than you think. And it might start with you deciding that your voice matters. That your silence costs something. That the world needs what you have to say, even if saying it is risky.

The research shows what most of us intuitively understand: silence spreads. But boldness spreads too.

The question is which one you'll choose to spread.

Key Takeaways

- Self-censorship is a rational cost-benefit calculation: when the risk of speaking exceeds the benefit, people stay silent

- Population boldness is asymmetrically powerful—if enough people refuse to self-censor, authorities cannot easily suppress dissent without escalating enforcement costs

- The Hundred Flowers trap shows how authorities use permission followed by punishment to gradually increase self-censorship over time

- Different governments use different approaches: Russia uses explicit rules, China uses ambiguity, the US outsources to tech companies

- Modern surveillance technologies lower enforcement costs for authorities, making control cheaper and more achievable

- Proportional punishment is more effective than draconian punishment because it allows people to find middle ground rather than forcing a binary choice

- Individual choices about speaking aggregate into population-level effects that determine whether authoritarianism can consolidate control

- Boldness doesn't permanently prevent authoritarianism but it buys time for circumstances to change, allowing resistance to potentially succeed

![The Science of Self-Censorship: Why We Stay Silent [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-science-of-self-censorship-why-we-stay-silent-2025/image-1-1767132470731.jpg)