SaaS Instability: How AI Is Redefining Enterprise Software [2025]

Introduction: The Era of SaaS Predictability Has Ended

For more than a decade, the B2B software industry operated like clockwork. Companies followed a predictable growth trajectory that looked almost identical across thousands of organizations: build a product, reach

This predictability was the defining characteristic of the SaaS boom. Investors loved it because they could model future growth with confidence. Customers embraced it because switching costs were high and workflow integration was complex. Employees trusted it because annual planning made sense. CEOs of public SaaS companies could deliver consistent quarter-over-quarter growth. The entire ecosystem was built on the assumption of continuity.

That era is now completely over. The transition wasn't gradual—it was shockingly rapid. In the span of 18 months, the B2B software landscape transformed from stable to fundamentally unstable. The catalyst wasn't a single event but rather a technological inflection point that caught most of the industry unprepared.

What's remarkable is how quickly public markets caught on to the threat. In January 2026, stock prices for established SaaS leaders were hammered, multiples compressed, and analysts began writing reports with titles like "Who Gets Disrupted?" Simultaneously, AI-focused companies experienced explosive growth and investor enthusiasm. Many observers treated this as a surprising or unexpected development. But for anyone who was actually building with modern large language models since mid-2024, this market reaction wasn't shocking—it was inevitable.

The real inflection point occurred six months earlier, when advanced AI models became genuinely capable of performing complex work autonomously. That's when the fundamental threat became clear: AI wasn't just another software feature to be bolted onto existing applications. Instead, it represents a replacement layer for entire categories of work that software previously just organized or facilitated.

This article explores what's actually driving SaaS instability, how it's forcing executives and investors to reconsider basic assumptions about the software business, and what companies need to understand about building and scaling in an AI-disrupted landscape. Unlike the optimistic narratives that position AI as simply "the next chapter" of SaaS, we'll examine the harder reality: fundamental business model assumptions are breaking down.

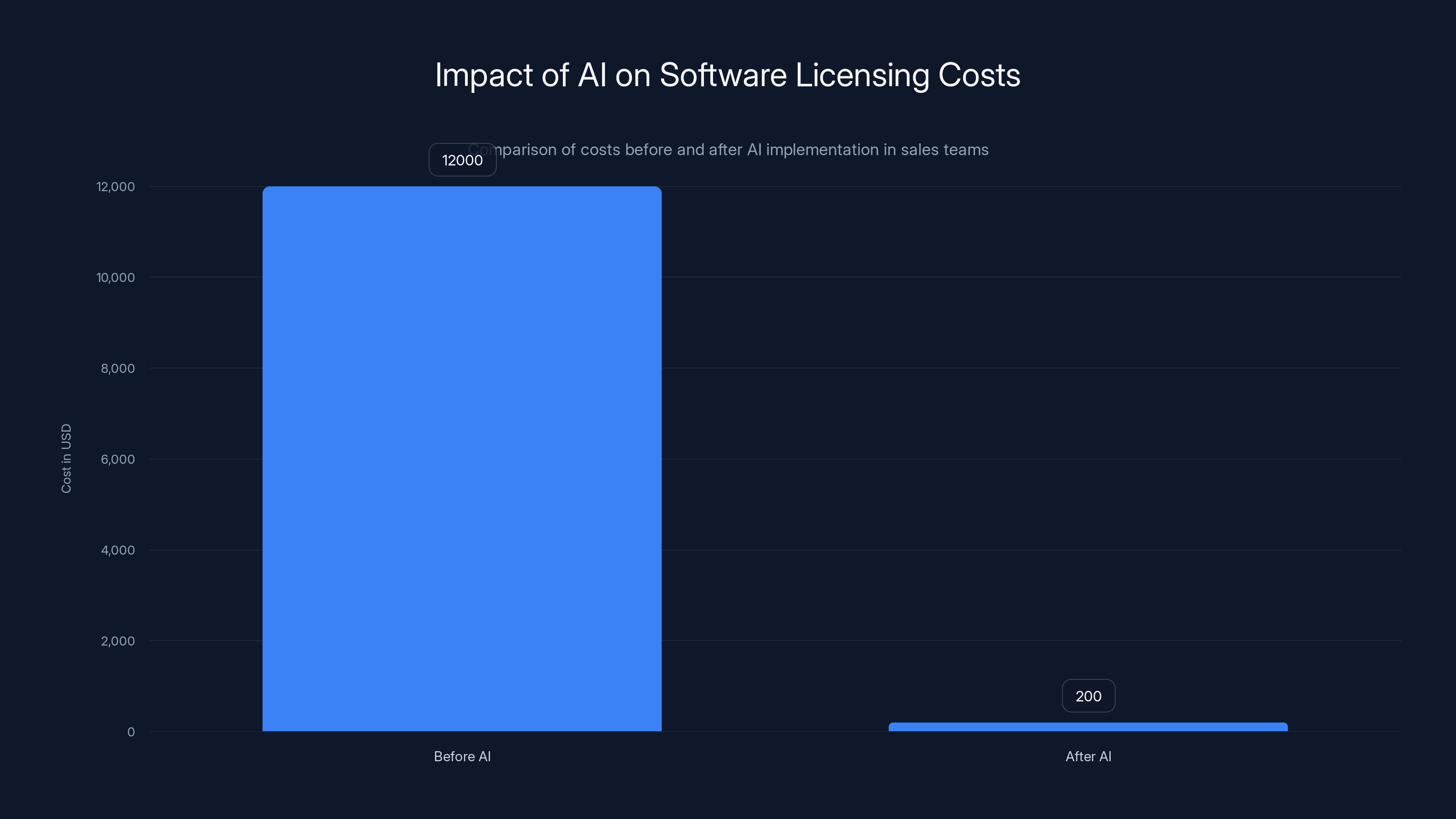

The introduction of AI in sales teams can drastically reduce software licensing costs from

The Decade of Boring Stability: What Made Old SaaS So Predictable

Why SaaS Products Remained Essentially Unchanged

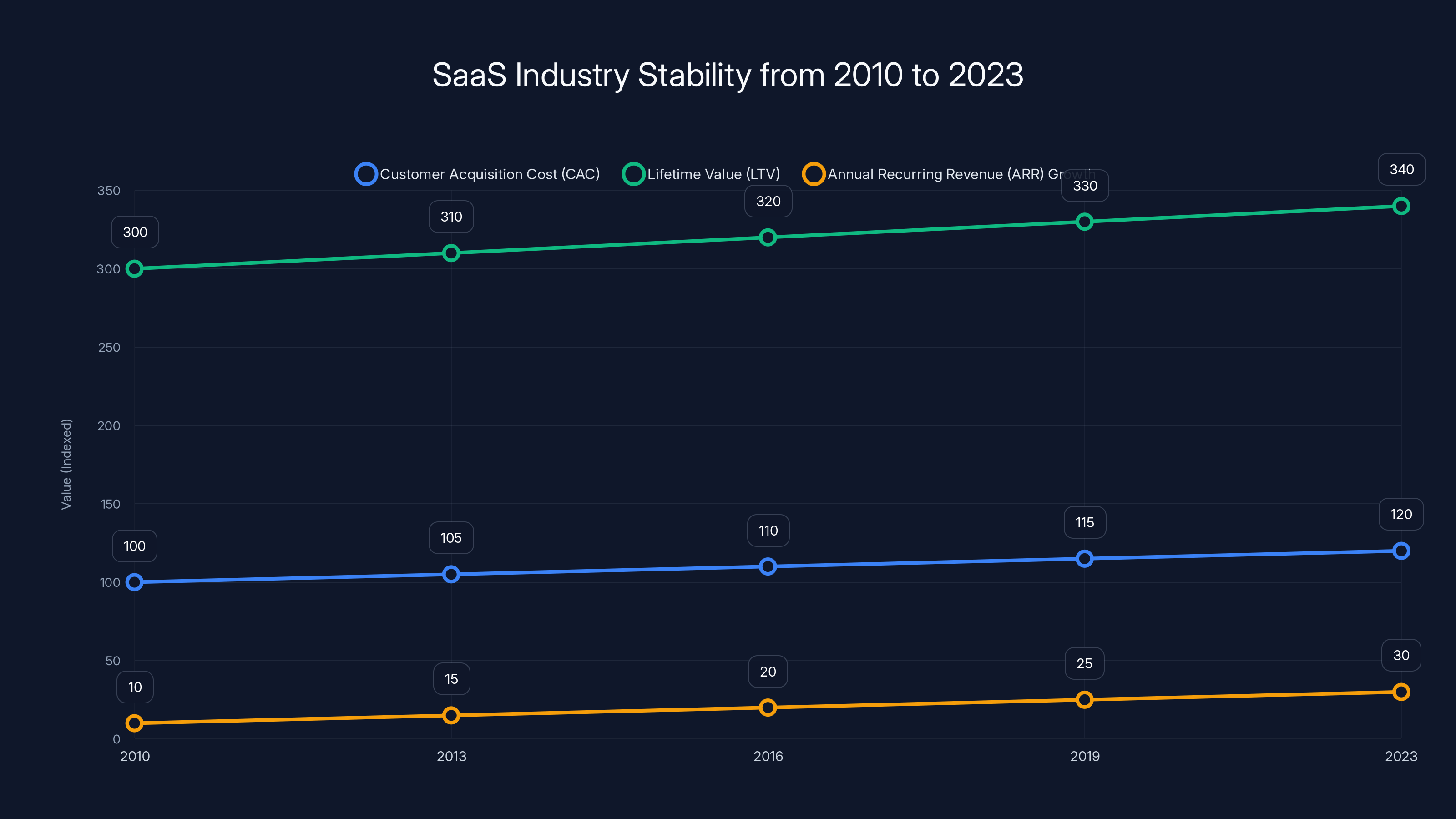

The stability of B2B software from 2010 to 2023 wasn't accidental—it was a natural consequence of the constraints that governed the industry. Software as a Service required significant upfront engineering investment to build a usable product, meaning companies typically had a 12 to 24-month runway before hitting product-market fit. Once a product achieved market fit, customer acquisition costs were relatively stable, lifetime value calculations were predictable, and competitive moats formed around data gravity and workflow switching costs.

A company selling customer relationship management software at

This consistency created enormous advantages. Product organizations could plan 24 to 36 months into the future with confidence. Engineering teams could allocate resources to incremental improvements because the fundamental technical architecture remained sound. Sales teams could develop consistent messaging because the value proposition didn't shift. This predictability extended to pricing models too—per-seat pricing, per-user licensing, and usage-based models remained relatively stable because the underlying unit economics made sense.

The Economics That Reinforced Stability

The financial model that governed SaaS growth during this era was extraordinarily favorable. Gross margins were typically 70-85% because software is inherently capital-efficient once built. Customer acquisition costs could be modeled with precision because customer cohorts behaved predictably. Churn rates stabilized as products matured. Upsell opportunities were consistent because customer expansion followed predictable patterns.

This financial stability allowed publicly traded SaaS companies to deliver reliable earnings reports, which in turn supported premium valuation multiples. For much of the 2010s and 2020s, SaaS companies traded at 8-12x revenue multiples, which meant that if you could demonstrate consistent growth and gross margins above 70%, the market would reward you handsomely. Companies like HubSpot, Zendesk, ServiceNow, and Workday embodied this playbook perfectly.

The fixed product nature also created powerful network effects and switching costs. Once a sales team had invested months training in Salesforce, rebuilding their entire process in a competitor's product was expensive and disruptive. Once financial data was stored in a specific system, moving to a new platform meant complex data migrations and business process redesigns. These switching costs meant that customer retention remained high, typically 95%+ for mature SaaS products.

How Product Roadmaps Worked in the Stable Era

During the predictable SaaS era, product roadmaps typically followed a consistent pattern: identify adjacent use cases within the same problem domain, build features to address those use cases, integrate with complementary platforms to reduce customer friction, and gradually move upmarket to larger enterprises with more complex needs. Every major SaaS vendor followed some version of this playbook.

Salesforce's roadmap essentially never changed between 2010 and 2023. It added better lead management, more sophisticated forecasting, deeper integrations with other enterprise systems, and gradually pushed into adjacent categories like marketing and service management. But the fundamental motion—organizing and surfacing customer interaction data—remained constant. HubSpot followed an identical playbook, starting with email marketing and expanding outward to CRM, sales, and service functions, but always focused on the same core: helping small to mid-market businesses organize their customer relationships.

This consistency meant that customer expectations remained stable. A company switching from one email marketing platform to another in 2018 was making a choice between marginally different execution of the same core functionality, not selecting between fundamentally different approaches. That consistency is now gone.

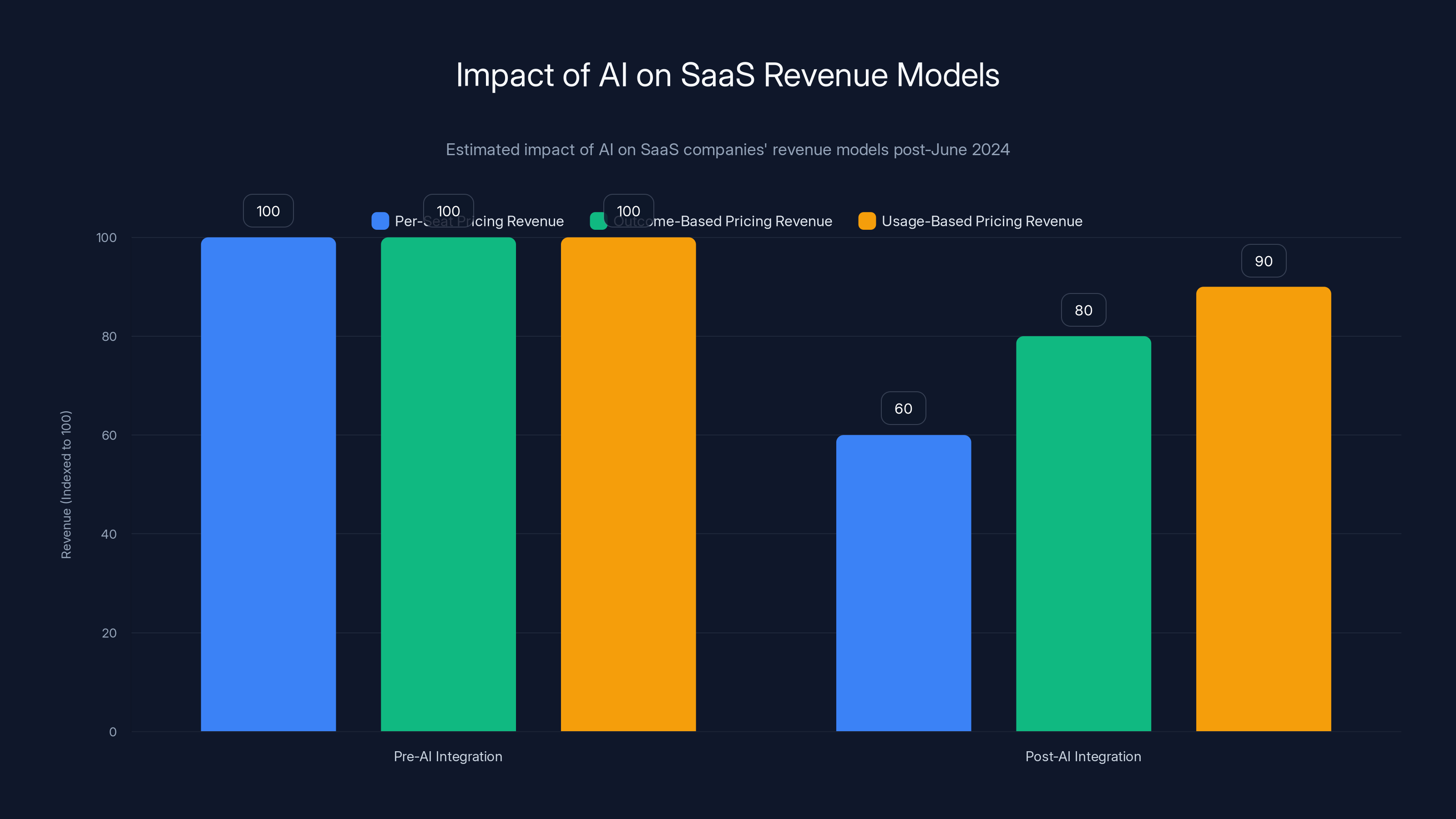

Estimated data shows a decline in per-seat pricing revenue post-AI integration, while outcome and usage-based models also face challenges but to a lesser extent.

The Inflection Point: June 2024 and the Claude Moment

When AI Stopped Being a Curiosity and Became a Threat

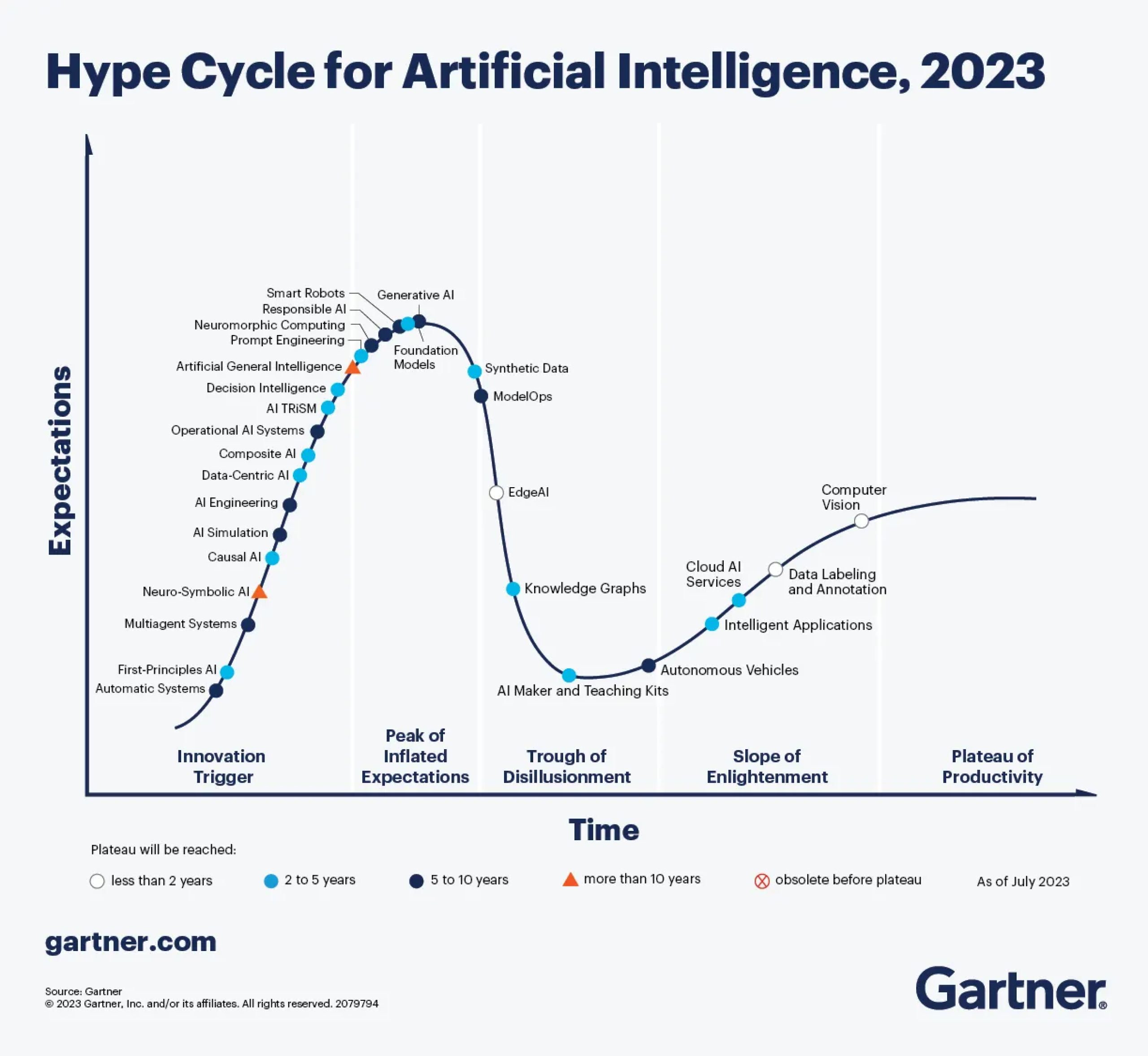

The public markets didn't realize something fundamental had changed until January 2026. But anyone actually building AI-powered products already knew the inflection point had arrived six months earlier, when Claude 3.5 Sonnet was released in June 2024. This specific AI model release wasn't just another incremental improvement in machine learning—it represented a genuine capability threshold that crossed from "interesting research" to "capable of replacing entire categories of human work."

Claude 3.5 Sonnet's particular capabilities made autonomous code generation practical for the first time at meaningful scale. Before that release, AI-powered coding assistants existed, but they required significant human oversight and often produced code that needed substantial revision. When Claude 3.5 Sonnet shipped, developers could describe in natural language what they wanted to build, and the model could generate functionally correct, production-ready code often requiring only minor adjustments or no adjustments at all.

This capability shift enabled a wave of AI-native products that hadn't been possible before. Lovable, which let anyone describe a web application they wanted to build and have an AI agent generate it end-to-end, became genuinely usable only after Claude 3.5 Sonnet. Replit's AI-powered code completion and application generation crossed from novelty to genuinely practical only with this release. Cursor, which positioned itself as an AI-first code editor, went from an interesting experiment to a product that was actually faster than traditional development workflows.

These products didn't exist first and then wait for AI to get good enough. They existed for years in various forms. But they didn't work in any meaningful way until Claude reached a certain capability threshold. That threshold, crossed in mid-2024, was the moment the industry should have recognized that something fundamental was shifting.

The Philosophical Shift: From Enhancement to Replacement

The paradigm shift represented by Claude 3.5 Sonnet's release can be summarized in two competing models of AI's role in work:

The Old Model: Software helps humans work more efficiently. A spreadsheet application helps accountants organize numbers faster. A CRM system helps salespeople manage customer relationships more systematically. Email helps teams communicate more effectively. In this model, AI can enhance these tools by making them slightly smarter, more predictive, or more automated, but the human remains central to the work process.

The New Model: AI does the work, potentially without humans in the loop. An AI agent can generate functional software code without human input. An AI system can draft sales emails, responses to customer inquiries, financial reports, and strategic analyses without human oversight or intervention. In this model, the software might orchestrate what the AI does, or the AI might not need orchestration at all.

This isn't a subtle distinction or a matter of degree. It's a fundamental category difference. When the primary unit of change from a software product is "features that make humans 10% more efficient," you can plan product roadmaps in 18-month increments with reasonable confidence. When the primary unit of change is "AI replacing entire functions," traditional product planning, pricing models, and business strategy become unstable.

Claude 3.5 Sonnet's release marked the moment this transition became undeniable for serious builders. Not the moment when AI might replace work someday. The moment when it was already replacing work in production applications.

Why January 2026 Was Simultaneously Late and Necessary

Public stock market reactions in January 2026 shocked many observers. Established SaaS leaders saw valuations compressed by 30-50% in a matter of weeks. The speed of the market repricing felt sudden. But from a market intelligence perspective, it was remarkably late. Everyone building seriously with modern AI models already understood the fundamental threat. The question wasn't whether AI would disrupt existing software businesses—it was when and how severely.

What the public market reaction actually represented wasn't the discovery of a new threat, but rather the moment when institutional investors were forced to confront and price in what individual technologists had already accepted. The gap between what builders knew and what institutions acknowledged had become impossible to ignore.

The irony is that public market multiples may have actually over-compressed, driven partly by panic and herd behavior. But that's a separate question from whether the underlying threat is real—it absolutely is.

The Core Instability: Fundamental Business Model Breakdown

Why Per-Seat Pricing Is Under Existential Pressure

For thirty years, the dominant pricing model in enterprise software has been per-user licensing. You pay a monthly fee for each person who can access the system. This model is so fundamental to enterprise software that it feels inevitable, but it only works if you're organizing human work. The moment work gets done by AI agents instead of humans, the math breaks entirely.

Consider a sales team that currently has five sales development representatives managing outbound prospecting, qualification, and initial contact. The SaaS tools supporting that team—email platforms, CRM systems, sales engagement tools—are typically priced per seat. If the company pays

Now introduce an AI agent capable of performing 80% of the work that those five SDRs do. The company doesn't need five SDRs anymore; they need one human supervising the AI system. Suddenly they need only one user license for their sales tools, cutting their software spending to $100-300 per month. The per-seat pricing model, which worked perfectly when seats equaled work, now incentivizes companies to minimize how many seats they actually need.

Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff explicitly acknowledged this pressure. When discussing AI's impact on Salesforce's own operations, he stated that Salesforce reduced headcount from 9,000 to approximately 5,000 people, explicitly because "I need less heads." Then, when discussing engineering hiring specifically, he said Salesforce was "seriously debating whether we're going to hire anyone this year." These aren't vague statements about future possibilities; they're acknowledgments that headcount reduction is actively happening inside one of the world's largest enterprise software companies.

This creates an impossible situation for SaaS vendors. If your customers are using your product to manage fewer people, your revenue automatically declines. The traditional response would be to increase pricing per seat to maintain revenue, but that makes it even more economical for customers to adopt AI agents and reduce headcount further.

Some vendors are attempting to pivot toward outcome-based pricing—charging based on revenue generated, deals closed, or customers served rather than seats used. But outcome-based pricing is brutally difficult to implement cleanly, creates misaligned incentives, and is nearly impossible for public company investors to model. When a company's revenue is unpredictable because it's tied to customer outcomes that might vary quarter to quarter, that company becomes significantly more difficult to value and significantly riskier to invest in.

Workflow Software as a Category in Crisis

Approximately half of the B2B software market consists of what might loosely be called "workflow software"—tools designed to route tasks between humans, ensure nothing falls through the cracks, and provide visibility into who's doing what. This includes project management tools, ticketing systems, approval workflows, document management systems, and task orchestration platforms.

The fundamental value proposition of workflow software is: "We will help you make sure that work assigned to human A gets completed, and when it's done, it automatically routes to human B." This works fantastically well when the work in question is genuinely something that requires human judgment, decision-making, and context understanding.

But what happens when 80% of the "work" that your workflow system orchestrates can be done by an AI agent without human involvement? The value of the workflow orchestration itself collapses. If an AI agent can draft a customer support response, why does it need to be routed to a human first? If an AI can generate a financial report, why does it need to be reviewed and approved by a manager? If an AI can handle 90% of a task, and you need a human to supervise the remaining 10%, does your workflow software that routes between 100% humans still have a role?

Workday CEO Carl Eschenbach acknowledged this pressure on earnings calls in real time. In Q1 of fiscal 2025, he stated: "We are seeing customers committing to lower headcount levels on renewals compared to what we had expected. We expect these dynamics to persist in the near term." One quarter later, he claimed that concerns about AI disruption were "completely overblown." By Q3, he had shifted to talking about "revenue per seat" instead of total seats, implicitly acknowledging that total seat growth wasn't happening but avoiding explicitly admitting to sustained headcount pressure.

This quarter-by-quarter narrative evolution—from admitting customers are renewing at lower headcount, to claiming concerns were overblown, to pivoting toward a different metric entirely—is the hallmark of a company adjusting its story in real time as market conditions force management to confront uncomfortable realities.

Data Gravity and Switching Costs in an AI-Mediated World

The traditional moat protecting enterprise software vendors was data gravity combined with workflow lock-in. Once customer data was stored in your system, moving it was extremely painful. Once business processes were built around your software, switching created massive operational disruption. These switching costs meant that even if a better competitor emerged, customers often remained loyal because the cost of switching was higher than the cost of staying.

But this moat assumes that the customer is paying for the platform because of the data and workflow structure. What happens when an AI layer can sit on top of any system of record and abstract away the interface?

Consider a customer who's been using a specific CRM system for five years. Their customer data lives in that system. Their sales process has been rebuilt around that system's workflow. The switching cost is enormous. But imagine an AI agent that can connect to that CRM through an API, extract relevant information, and present it in a completely different interface tailored specifically to what the sales rep needs. Now the switching cost isn't between CRM systems—it's between AI agents.

The AI layer becomes the meaningful interface, and the underlying data repository becomes commoditized. This is precisely what companies like Klarna are exploring. Klarna's CEO stated: "Thanks to AI agents and AI engineers getting prolific, you can rebuild most enterprise SaaS functionality, host for super cheap, and get basically 90%+ functionality." This represents a fundamental threat to the data gravity moat that protected incumbent SaaS vendors.

It's worth noting that Klarna remains somewhat of an outlier. Most enterprises aren't yet rebuilding their entire software infrastructure around AI agents. But as the saying goes: the things that are outliers have a way of becoming the norm faster than anyone expects.

Estimated data shows a stable increase in key SaaS metrics from 2010 to 2023, reflecting the industry's predictable growth and stability.

What's Breaking: The Assumptions Companies Got Wrong

Three-Year Product Roadmaps Are Now Obsolete

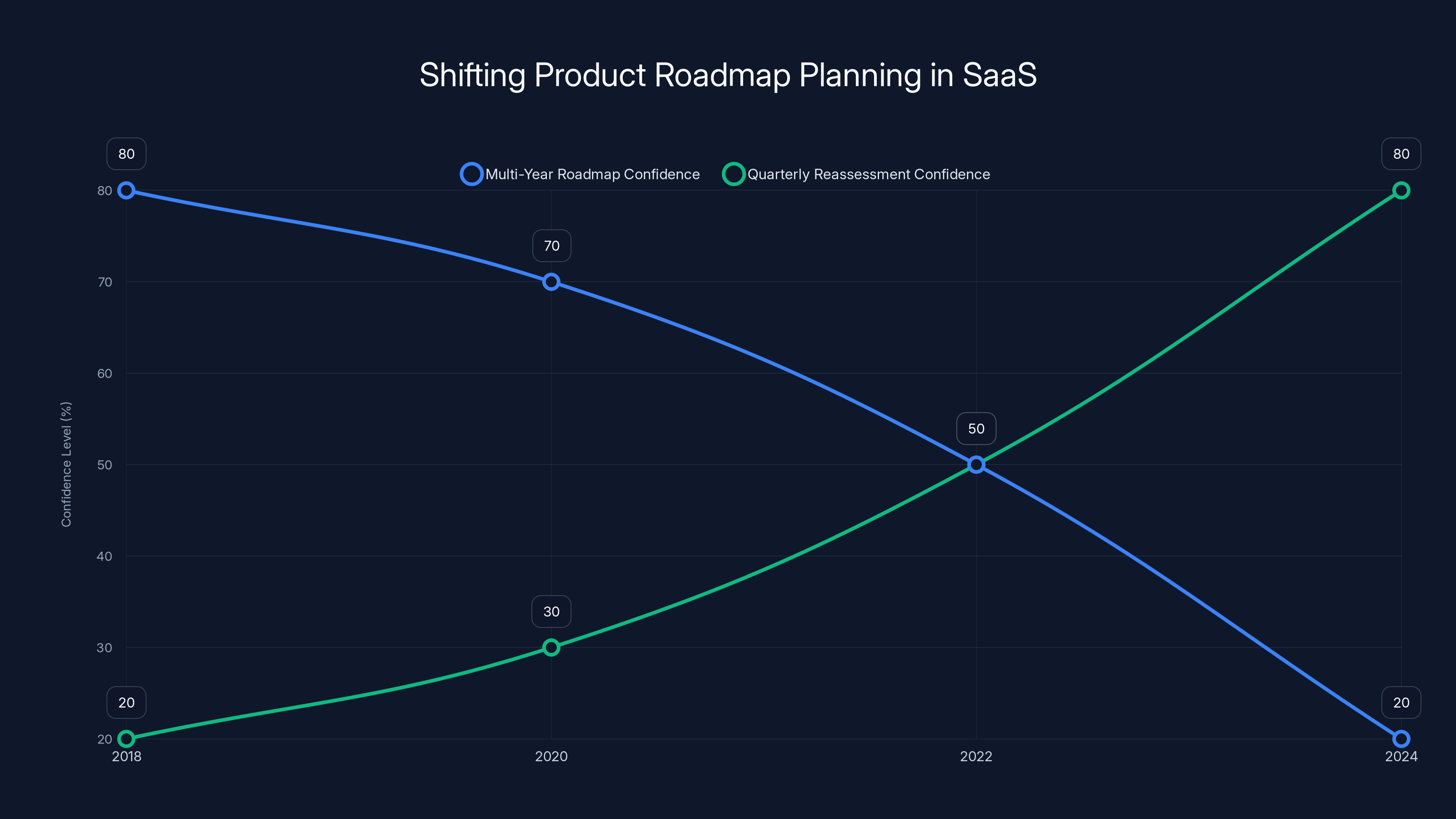

During the stable SaaS era, product teams could commit to multi-year roadmaps with reasonable confidence. You could identify problems you wanted to solve two or three years out and build toward them incrementally. Competitors might emerge, technology might shift slightly, but the fundamental problem you were solving and the approach you were taking would likely remain valid.

That planning horizon is now completely broken. The problem isn't that change is accelerating—change has always been part of software. The problem is that the fundamental nature of the problem being solved can shift in ways that render entire product categories obsolete.

Consider a company building project management software in June 2024. They might have planned a roadmap around improving their timeline visualization, adding better integrations with other tools, expanding their mobile experience, and adding AI-powered task recommendations. By December 2024, after Claude 3.5 Sonnet had been available for six months, a new class of products had emerged that could generate the entire project plan based on a natural language description. That makes several of your planned features almost irrelevant.

Product leaders are now discovering that two-year roadmaps need to be restructured around quarterly reassessment checkpoints where you fundamentally reconsider whether the problems you planned to solve are still the most important problems. This requires a different organizational approach—more fluid resource allocation, more flexibility in commitment, more systematic monitoring of whether fundamental category threats are emerging.

Customer Expansion Models Are Broken

For the past decade, SaaS companies have built growth models around the principle of land-and-expand: acquire a customer in one department or at one use case, then gradually expand usage across the organization. You'd land in the marketing department with an email marketing tool, then expand to sales, then to customer service, then to the broader enterprise. The flywheel was almost automatic because more usage meant more value, and more value meant more willingness to pay.

AI disruption breaks this model completely. If a customer can now do work with AI agents that previously required multiple tools and multiple people, the total addressable market within that customer actually contracts. They need fewer software licenses, fewer integrated tools, and a simpler technical stack. Companies that planned their growth around expanding from three users to thirty users across a customer might instead see customer deployments shrink from thirty users to five.

This isn't a hypothetical concern—it's happening in real time at large enterprises. Workday, Salesforce, and other leaders are all explicitly dealing with customers committing to lower headcount on renewals. That means the expansion revenue that was supposed to be automatic now needs to be replaced by new customer acquisition, which is considerably more expensive and inconsistent.

Valuation Multiples Are Likely Permanently Lower

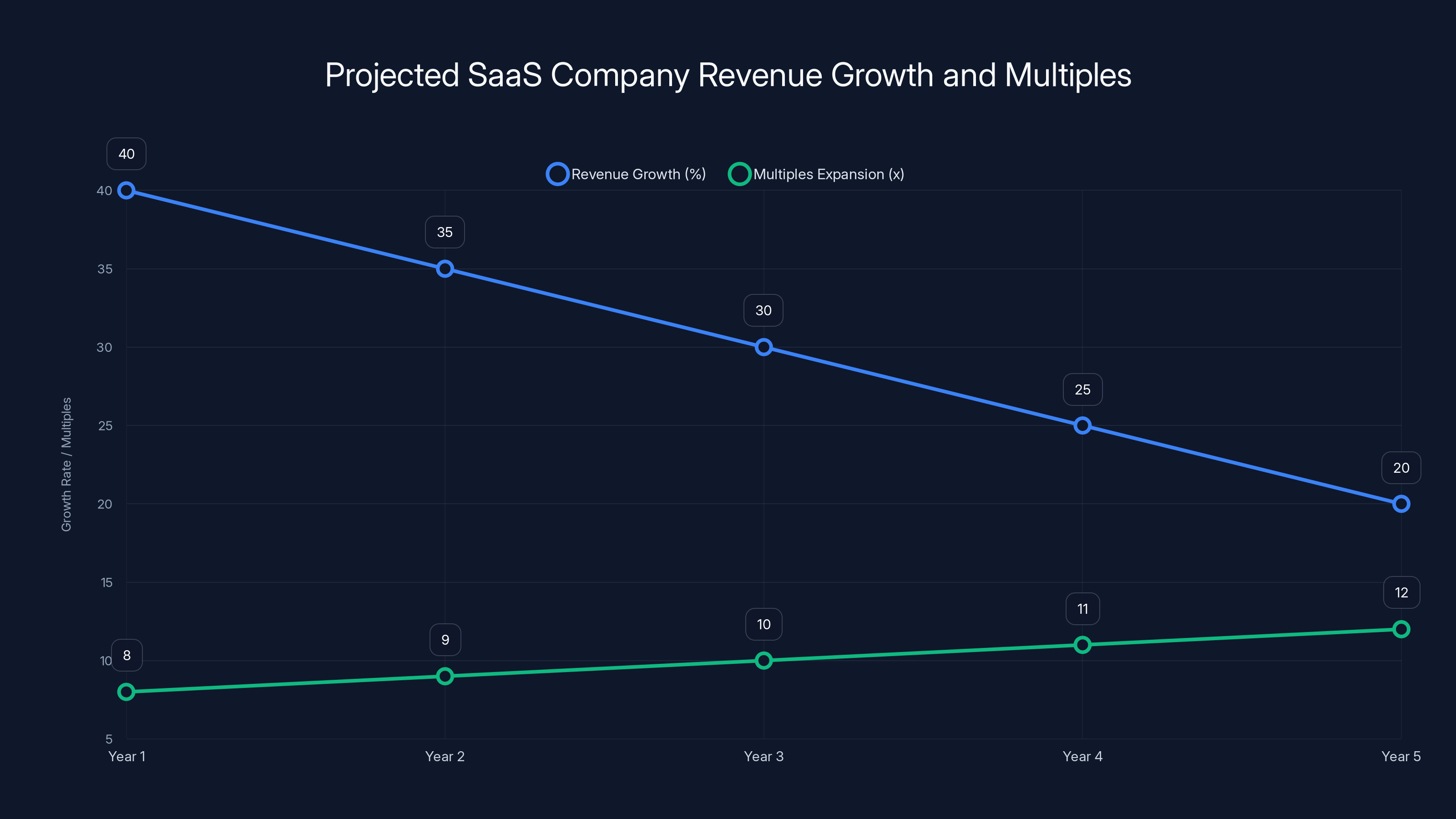

During the growth-at-all-costs era of SaaS (roughly 2010-2021), enterprise software companies would trade at 8-12x revenue multiples because investors had confidence that growth would compound indefinitely. The business model was predictable, switching costs were high, and the market was still in the early stages of digital transformation. SaaS leaders would reliably achieve 20-40% year-over-year growth for a decade or more.

Those assumptions are now broken. Investors can no longer assume that because a company is a leader in category X, it will maintain leadership if category X gets disrupted by AI. Workday might be the enterprise resource planning leader, but if AI agents can handle most ERP functions and AI-native competitors can be built from scratch specifically to work alongside AI systems, what does leadership mean?

Valuation multiples are unlikely to ever return to pre-disruption levels for broadly-exposed legacy categories. This doesn't necessarily mean those companies will fail or decline, but it does mean that the multiple arbitrage that made early SaaS investors wealthy is largely gone. The high-multiple environment that rewarded predictable software vendors is being replaced by a differentiated environment where only companies with genuine defensibility in an AI world command premium valuations.

For startup founders and venture investors building new companies, this reality is even more important. The idea that you can build a product that solves a problem, achieve 20%+ growth rates indefinitely, and eventually exit for a premium multiple is significantly less certain. The value of building something defensible from day one, rather than optimizing for short-term growth, has increased dramatically.

The Incumbent Response: Reading Between the Lines of Earnings Calls

What Executives Are Really Saying (When You Decode Carefully)

The leadership of the world's largest B2B companies know exactly what's happening. You can see it in their earnings call language, if you read carefully between what they're actually saying and what they're trying to avoid admitting.

Workday provides the clearest example of executives adjusting their narrative in real time. In Q1 FY25, CEO Carl Eschenbach didn't hide the problem: "We are seeing customers committing to lower headcount levels on renewals compared to what we had expected. We expect these dynamics to persist in the near term." That's a direct acknowledgment that an existential threat exists. Customers are actively using AI to reduce headcount, and the company's primary unit of revenue (seats) is contracting.

One quarter later, in Q2 FY25, Eschenbach completely changed the framing: "Your customers are... working with large language models and AI models. This whole concern around AI disruption and the potential negative impact on seat-based models are completely overblown." This is what executives say when they know the earlier admission was too honest and the market reacted negatively. They're trying to reframe the threat as overblown rather than addressing it directly.

By Q3 FY25, the narrative had shifted again, but more subtly: "Your customers are growing headcount slowly right now... We're focused not just on seats, but actually revenue per seat." Notice that he didn't say headcount is growing. He said it's growing slowly. And he pivoted the metric from total seats (which are shrinking) to revenue per seat (which can stay flat even as total seats decline if you raise prices). This is the classic executive move of shifting metrics when the ones you were using start looking bad.

Salesforce's Marc Benioff has been more direct about the impact at his own company. When discussing cost reductions, he stated: "I've reduced it from 9,000 heads to about 5,000, because I need less heads." Then, regarding new hiring in engineering: "In engineering this year at Salesforce, we're seriously debating—maybe we aren't going to hire anyone this year." These aren't vague statements about the future. They're clear admissions that the company is actively reducing headcount because of AI, and they're uncertain whether they'll hire additional engineers at all.

The significance of that statement can't be overstated. Salesforce is a software company. Software companies hire engineers to build products. If the leader of the largest B2B vendor on the planet is debating whether to hire any engineers at all, that's not a sign of business-as-usual. It's a sign of fundamental business model pressure.

Pricing Model Transitions Are Underway (And Failing)

Multiple large SaaS vendors have tried to transition away from per-seat pricing toward alternative models like usage-based pricing or value-based pricing. These transitions are universally failing because neither the companies nor their customers actually want them.

Usage-based pricing initially seemed attractive to vendors because it would decouple revenue from headcount. If we charge based on transactions, API calls, or data processed instead of seats, then customers adopting AI agents wouldn't see their bill decline. But customers hate usage-based pricing because it creates unpredictable costs and incentivizes them to minimize usage rather than maximize it. If you know that every additional transaction costs money, you're more likely to find ways to reduce transactions than if you're paying a fixed monthly fee per user.

Value-based pricing—charging customers based on the value they receive or outcomes they achieve—is theoretically elegant but practically impossible to implement. How do you measure whether a customer achieved a specific outcome? How do you prevent disputes about whether the vendor deserves credit for a particular outcome? How do you model predictable revenue when your pricing is based on customer outcomes that might vary significantly quarter to quarter? Public company investors hate value-based pricing because it makes financial forecasting nearly impossible.

So large SaaS vendors are stuck. They can't charge per seat if customers are actively minimizing seats. They can't switch to usage-based pricing because customers won't accept it. They can't use value-based pricing because investors won't fund it. This is the fundamental bind that's driving the instability.

The confidence in multi-year product roadmaps has decreased significantly, while the need for quarterly reassessment has increased, reflecting the dynamic nature of the SaaS industry. Estimated data.

The Uncertainty: What Leaders Are Actually Unsure About Now

Will Switching Costs Persist in an AI-Mediated Environment?

One of the clearest sources of instability for SaaS leaders is genuine uncertainty about whether the traditional moats that protected them will continue to exist. For thirty years, switching costs were the primary defense against competition. You couldn't easily switch from one CRM to another because of data migration complexity, workflow restructuring, and retraining requirements.

But if an AI layer abstracts away the underlying system of record, does that moat still exist? If a customer could connect an AI agent to their current CRM, move to a completely different CRM, and have the AI agent abstract away the differences so the user experience remains identical, the switching cost has effectively disappeared.

Management teams at large software companies genuinely don't know whether this will happen. It might not. Enterprise customers have other incentives to stay with established vendors beyond just switching costs—deep integration with complex business processes, mature tooling, large internal training investments. But the uncertainty itself is destructive to business planning.

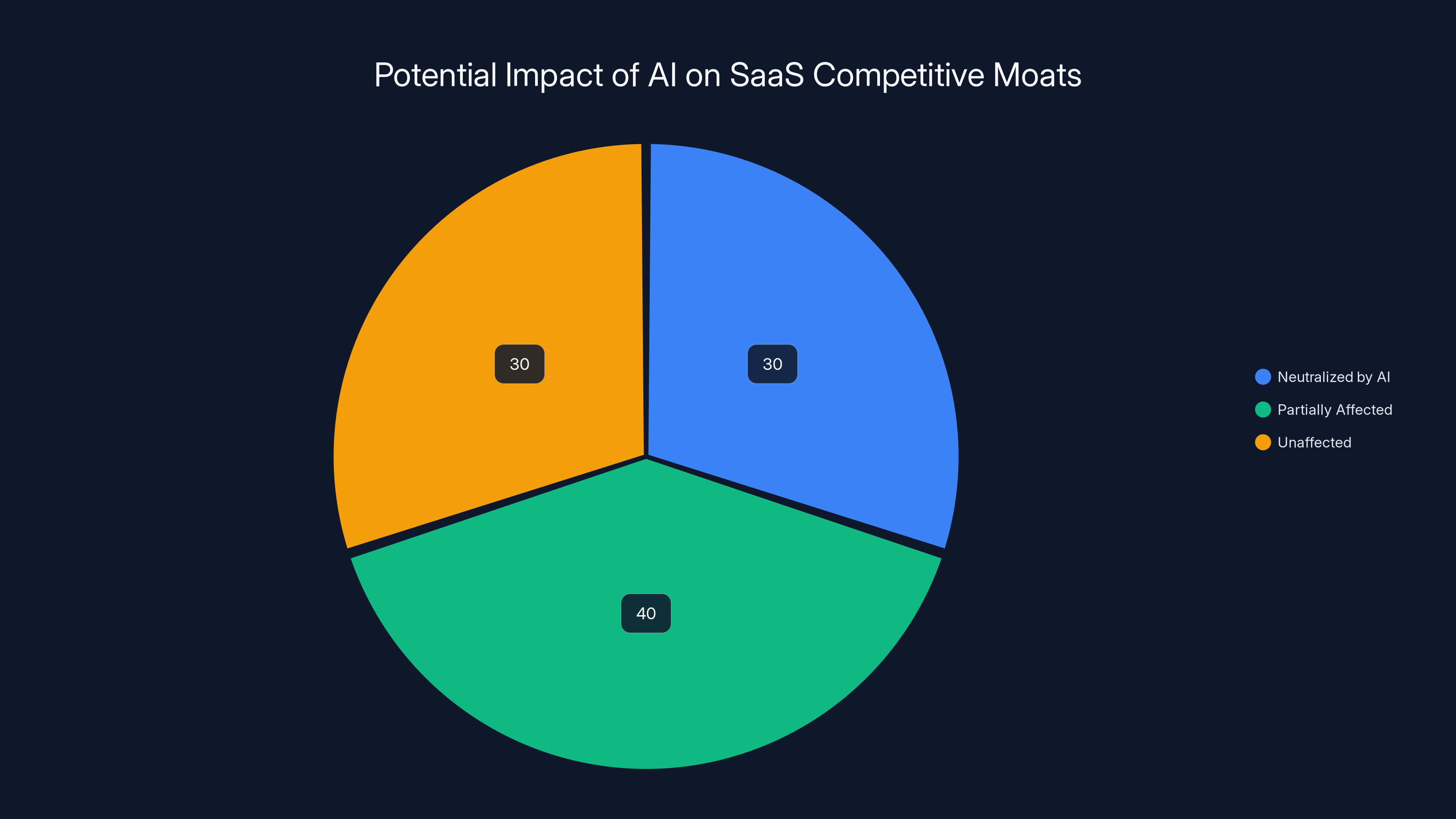

If there's even a 30% chance that your primary competitive moat gets neutralized by AI abstraction layers, that changes how you invest, what you charge, and what your long-term growth looks like. Companies can't plan confidently when fundamental assumptions about their competitive position are in question.

Will "Workflow Software" Still Be a Meaningful Category?

Approximately half the B2B software market exists to organize human workflow. But what happens if 80% of the work that gets routed through those workflows can be done by AI agents without human involvement?

Does your project management software still matter if most tasks get completed by AI without human assignment? Does your approval workflow software matter if AI systems can self-supervise for most cases and only escalate to humans for edge cases? Does your document management system matter if AI can generate most documents automatically?

Large software leaders genuinely don't know the answer. The workflow orchestration might still be valuable for the remaining 20% of tasks that require human involvement, but the total addressable market would be 80% smaller. Or maybe new types of workflow emerge where you're orchestrating AI systems instead of humans, with completely different requirements and different vendors.

The uncertainty creates a planning crisis because you don't know if your core product category survives in meaningful form.

How Much of Enterprise Work Gets Automated?

There's a spectrum of possibilities about how much enterprise work actually gets handled by AI systems in the next 3-5 years. On one end, AI handles maybe 20-30% of work, mostly in content generation and basic task completion. On the other end, AI handles 70-80% of work, with humans primarily in supervisory roles. That 50-percentage-point difference in automation rates creates completely different business models, competitive landscapes, and growth trajectories.

No one actually knows where we'll land. The optimists think AI will plateau at 30-40% automation in enterprise contexts because of the complexity of business judgment. The pessimists think we'll hit 70%+ automation much faster than expected. The middle ground might be right, but even the middle ground represents a massive difference from the stable era where automation was incremental.

Large software companies can't plan their business based on something this uncertain.

What Happens to Professional Services?

Much of the software industry's business model is built on selling software plus professional services. A company pays

But if AI can handle much of the customization and implementation work that consultants previously did, where does the services margin go? Can it be replaced with managed services, where the vendor operates AI agents on behalf of the customer? Or does that cannibalize the license revenue?

Large software vendors don't have good answers. Services teams have been growing substantially (Salesforce's services organization is massive), but the economics of those services are changing because the work is being done by AI instead of expensive consultants.

Specific Product Categories Under Pressure

CRM and Sales Engagement Tools

Customer relationship management was one of the earliest categories to be disrupted by enterprise software, and it may be one of the first to be disrupted again by AI. The core function of a CRM is to organize customer interaction data and make it accessible to salespeople. But if an AI agent can handle initial customer outreach, qualification, and most of the routine communication tasks, the role of the CRM changes fundamentally.

Salesforce is actively dealing with this pressure. A significant portion of Salesforce's revenue comes from per-seat pricing for CRM licenses, but companies using AI for outbound prospecting need fewer sales development representatives. This directly impacts Salesforce's revenue. Eschenbach's earnings call statements about customers committing to lower headcount largely stemmed from this specific pressure in the sales organization.

Companies like Outreach, 6sense, and Salesloft that built narrowly-focused sales engagement tools are even more exposed because their entire value proposition depends on salespeople using their systems. If AI handles 70% of the prospecting and outreach workflow, the need for specialized sales engagement tooling diminishes significantly.

Customer Support and Knowledge Management

Customer support software, including platforms like Zendesk, ServiceNow, and Freshservice, manages the workflow of routing customer inquiries to support agents. But if an AI system can handle 80% of customer inquiries directly, the fundamental value of the platform shifts. The workflow routing becomes less important than the AI capabilities.

Zendesk and similar vendors have responded by building AI capabilities directly into their platforms. But this creates a peculiar situation where the traditional vendor is competing against AI-native alternatives that might not need the workflow routing component at all. An AI agent might sit between customers and company databases, answering questions directly without needing to route anything to a human. The workflow software becomes superfluous.

Knowledge management and documentation platforms like Notion, Confluence, and SharePoint face a similar threat. Much of their value depends on employees searching through documentation and tribal knowledge to find answers. But if an AI agent can ingest that documentation and provide answers directly, the need for complex knowledge management systems changes. Why maintain a detailed documentation system if an AI can generate answers on demand?

Project Management and Work Orchestration

Project management software like Asana, Monday.com, Jira, and ClickUp is built around assigning tasks to humans and tracking their completion. But if AI agents can handle most tasks independently, the value proposition shifts. The remaining 20% of tasks that require human involvement might not justify the expense of a comprehensive project management system.

There's a potential future where project management tools become much simpler (focused on the 20% of work that genuinely requires human coordination) or where they evolve into AI orchestration platforms. But that's not the same as the category existing in its current form.

Accounting and Financial Reporting Tools

Accounting software like NetSuite, QuickBooks, and Xero is built around helping humans organize financial data and produce reports. But AI can now generate financial reports, reconcile accounts, handle tax calculations, and create audit documentation with minimal human involvement. The human role in accounting is shifting from doing work to supervising AI systems.

Intuit has acknowledged this shift by building AI into QuickBooks. But the business model pressure is real—if AI can do what previously required expensive accountants, companies will do less with fewer people, which means less software revenue per company.

Estimated data suggests a 30% chance that AI could neutralize traditional SaaS switching costs, with 40% partially affected and 30% remaining unaffected.

The Competitive Landscape is Inverting

Why AI-Native Products Have Structural Advantages

Traditional SaaS products were built around organizing human work. They optimize for user interface design, workflow clarity, and integration with other human-facing tools. An AI-native product is optimized for something completely different: enabling AI systems to accomplish work autonomously.

An AI-native product might have a terrible user interface because most interactions don't involve humans. It might have unusual data structures because they're optimized for AI processing rather than human comprehension. It might have pricing that's completely different because it charges for AI processing rather than seats.

These differences mean that a traditional SaaS company can't simply add AI capabilities to their existing platform and expect to compete with AI-native companies. The architecture is different, the optimization targets are different, and the business models are different. A traditional CRM optimized for human salespeople will never be as efficient at handling AI-assisted sales processes as a system built from the ground up for that purpose.

This is similar to how web-native companies like Amazon and Netflix eventually outcompeted traditional retail and entertainment companies, not because they were better at the original business model but because they were optimized for an entirely different model. Kodak didn't lose to a better film company; it lost to a company optimized for digital photography. Similarly, large SaaS vendors might not lose to competitors with better software, but to competitors optimized for an AI-first world.

The Commoditization of Horizontal Functions

Many core SaaS functions are in the process of becoming commoditized. Email management, basic CRM functionality, simple project tracking, document generation, and basic financial reporting can now be done reasonably well by AI systems combined with APIs to access data. This means that companies no longer need specialized, expensive software for many of these functions.

Why license expensive specialized project management software if you can connect an AI agent to your data and ask it to manage projects? Why pay for a specialized document generation system if an AI can generate documents based on templates and data? These horizontal functions are becoming commodities, which drives prices down and margins down for vendors that depend on them.

The remaining value in enterprise software will likely concentrate in functions where AI can't be applied as easily or where competitive differentiation still matters. But the number of such functions is shrinking.

What Building in This Era Actually Requires

Planning in Quarters, Not Years

For companies building enterprise software in this environment, planning cycles need to compress dramatically. Three-year product roadmaps are obsolete because too many fundamental assumptions might change in that timeframe. Instead, planning needs to happen quarterly with fundamental reassessment of whether the problem being solved is still the most important problem.

This requires a different organizational capability: the ability to pivot quickly, abandon investments when new information emerges, and reallocate resources fluidly. It's the opposite of traditional SaaS companies where once you commit to a product direction, you execute that direction for multiple years.

Building for AI Integration, Not AI Replacement

For the next few years, the safest bet for new software products is to optimize for integration with AI systems rather than trying to out-AI the AI companies. A software platform that makes it easy for customers to connect their data to AI agents will remain valuable longer than a platform that tries to embed AI capabilities directly.

This suggests a shift toward infrastructure-focused software: platforms that make it easier to connect various data sources to AI systems, orchestrate AI workflows, monitor AI agent behavior, ensure compliance when AI is making decisions. These functions will remain valuable even as AI becomes more capable.

Focusing on Defensible Niches Rather Than Horizontal Functions

The winners in an AI-disrupted world will likely be companies that own specific, defensible niches rather than trying to be horizontal platforms. If you own the specific workflow around pharmaceutical sales, you might be defensible because the domain-specific knowledge combined with data you accumulate creates real competitive advantage. If you try to be a generic CRM that competes on breadth of features, you're in a commoditized market where AI-native competitors can outmaneuver you.

This represents a significant shift from the SaaS trend of the past decade, where the winners were increasingly horizontal platforms (Salesforce, HubSpot, Workday) that could serve many industries. The future might favor specialization over horizontality.

This chart illustrates the traditional SaaS growth model with declining revenue growth rates and increasing multiples over five years. Estimated data highlights the past predictability of SaaS investments.

What This Means for Investors

The Death of the Predictable SaaS Multiple

For the past 15 years, investors could achieve acceptable returns by finding large, growing SaaS companies and expecting consistent multiple expansion as the company matured. Buy Okta at

That playbook is largely dead. Multiple expansion is unlikely to happen for broadly-exposed legacy vendors. The question for investors now is whether the company can maintain growth even as its core product category faces disruption. That's a much harder question to answer, and it commands lower multiples.

AI Disruption Creates Selection Pressure

The companies that survive and thrive in this environment will be those that can adapt quickly, that own specific defensible niches, that have already begun the transition to AI-first operating models, or that can provide infrastructure that enables others to adapt. Companies that are slow to recognize the threat, that are dependent on traditional per-seat models, or that have built moats that are easily bypassed by AI abstraction layers will face pressure.

This is actually excellent news for venture investors because it creates differentiation. In the stable SaaS era, almost any company that had decent product-market fit and could grow 30%+ would eventually get acquired or go public at a reasonable multiple. In this era, only the companies that are explicitly designed to compete in an AI world will achieve premium outcomes. That's more selective, but the winners are more defensible.

Public Market Repricing Isn't Finished

The stock market repricing in January 2026 was real, but it likely represents just the beginning of institutional repricing of enterprise software risk. As it becomes more clear over the next 12-24 months which business models are actually under pressure versus which are more resilient, further repricing is likely. The companies that have begun the transition most successfully will likely see their multiples stabilize and potentially expand. Those that are slow to adapt will face ongoing pressure.

Preparing for Continued Instability

What Traditional SaaS Companies Need to Do Immediately

Large enterprise software companies that were built on stable product foundations need to make several moves now, not over the next 3-5 years. First, they need to honestly acknowledge the threat and set aside resources to explore AI-native alternatives to their existing business model. Second, they need to build capability to move quickly—streamline decision-making, reduce planning cycles, and increase the ratio of experimentation to execution.

Third, they need to prepare for pricing model changes. This might mean building outcome-based pricing infrastructure, preparing customers for different licensing models, or building managed services where the vendor operates AI on behalf of the customer. None of these are easy, but delayed action makes them harder.

Fourth, they need to genuinely consider whether parts of their business should be disrupted from within before external competitors disrupt them. This is painful but necessary.

What New Companies Need to Build

New companies building in this era should explicitly optimize for AI integration from day one. This means building APIs and data access patterns that make it easy for AI systems to use your platform. It means thinking about your product as potentially being operated by AI agents rather than just humans. It means building for integration rather than comprehensiveness.

New companies should also be cautious about building broadly horizontal products that address functions that might be commoditized by AI. A horizontal expense management platform might face pressure if AI can handle most expense categorization, approval, and reporting. A vertical solution focused on a specific industry or function might be more defensible.

The Shift Toward Infrastructure

One of the clearer trends emerging is that value is shifting toward infrastructure—platforms, tools, and services that enable others to work with AI systems. Companies building tools to make it easier to connect data to AI, orchestrate AI workflows, monitor and govern AI systems, or ensure compliance when AI is making decisions will likely remain valuable across multiple AI-enabled futures.

This suggests that infrastructure investment is likely to be rewarded in the coming years in ways that horizontal software investment might not be. It's worth considering whether your product is closer to horizontal software (potentially disrupted) or infrastructure (potentially defensible).

How to Navigate as a Software Buyer

Evaluating Software With Instability in Mind

If you're a software buyer, the instability in the B2B software market creates both risks and opportunities. The risk is that you might invest in a platform that gets disrupted by AI faster than the vendor can adapt. The opportunity is that you can potentially negotiate better terms if you're aware that the vendor is facing structural pressure.

When evaluating new enterprise software, ask explicit questions about the vendor's roadmap for AI integration. Not AI features, but AI integration—how will this software work when AI systems are doing much of the work that humans currently do? Does the vendor have a credible answer? If they say they're building AI features but haven't thought about fundamental business model questions, that's a sign they might not be aware of the threat they're facing.

Also consider the defensibility of the vendor's position. Do they own unique, defensible data? Is their primary moat based on switching costs that might be erosion by AI abstraction layers? If so, they might face pressure even if they try to adapt. If their moat is based on genuine domain expertise or specific industry knowledge, they're likely more resilient.

Negotiating Software Contracts in an Unstable Market

The instability in the market actually gives software buyers more negotiating leverage than they've had in years. If a vendor is facing structural pressure, they might be willing to offer better terms, longer contracts at favorable pricing, or outcome-based pricing if it helps them lock in predictable revenue.

Consider negotiating for pricing models that align your incentives with the vendor's incentives even as the world changes. If you're reducing headcount, consider how your software pricing will change. Is the vendor willing to negotiate a price that reflects lower headcount usage? If not, that's valuable information about their confidence in their own business model.

Using AI to Reduce Software Costs

One of the valid responses to instability in the enterprise software market is to reduce how much software you're using and replace some of that functionality with AI agents. If an AI agent can handle 70% of what your expensive CRM does, you can potentially negotiate lower CRM spending and invest the savings in AI infrastructure instead.

This isn't risk-free—you lose some functionality and integration. But in an era of vendor instability, reducing dependence on any single vendor might actually reduce your overall risk even as it increases your technical complexity.

Long-Term Implications: What Enterprise Software Looks Like in 2028

The Probable Consolidation

As instability persists, we're likely to see significant consolidation among enterprise software vendors. The marginal players without specific defensibility will be acquired, consolidated, or shut down. The winners will be companies that found a defensible niche or that can operate efficiently in a world where traditional per-seat pricing no longer works.

This consolidation has already begun. Strategic acquisitions by larger vendors are partly defensive moves to try to acquire capabilities or defensibility in an uncertain market. But some of these acquisitions will prove to have been expensive bets on businesses that didn't end up being defensible.

The Shift Toward Specialization

The broad horizontal platforms that dominated the SaaS era (Salesforce, HubSpot, Workday) will likely remain large and important. But they won't be the growth engines they were in the past. Instead, the higher growth and higher-multiple companies will be increasingly vertical, deeply specialized solutions that own specific workflows, industries, or use cases.

This doesn't mean horizontal platforms will decline. It means their growth will moderate, their role will become more foundational and less differentiated, and the exciting growth stories will be elsewhere.

The Infrastructure Explosion

The companies that will likely do best are those building infrastructure for an AI-enabled world. Companies that make it easy to connect AI systems to data, manage AI workflows, ensure compliance when AI is making decisions, and monitor AI system behavior will remain valuable regardless of how the disruption plays out.

This infrastructure layer might become as important as the applications themselves. Just as the internet created a need for infrastructure companies (Akamai, Cloudflare, etc.), AI adoption is creating a need for infrastructure to govern, monitor, connect, and operate AI systems.

Conclusion: Making Sense of Instability

The B2B software industry is in the early stages of a fundamental transformation driven by advances in AI capabilities. This isn't hype or future speculation. The instability is happening now. Public markets recognized it in January 2026, but the reality has been unfolding for executives and builders since Claude 3.5 Sonnet's release in mid-2024.

What makes this moment different from previous software disruptions is the speed of capability transition and the breadth of impact. Previous disruptions (cloud, mobile, etc.) created new platforms but didn't fundamentally break the primary unit of software economics (per-seat pricing) or make entire categories of software obsolete. AI is doing both, simultaneously.

For incumbent vendors, this creates existential uncertainty. The business model assumptions that made the industry predictable are breaking down. Customer growth expectations are shifting. Competitive moats that protected market leaders are eroding. The financial model that public market investors relied on is unstable. Executives know this intellectually, even when they're not stating it explicitly.

For investors, the opportunity lies not in predicting exactly how disruption will play out, but in recognizing that instability creates selection pressure. Companies that are explicitly designing for an AI-first world will outcompete those trying to retrofit AI onto legacy architectures. Infrastructure companies supporting AI adoption will likely outperform horizontal platforms that built their empires on per-seat pricing.

For software buyers and operators, the instability is simultaneously a risk and an opportunity. The risk is that you might over-invest in software from vendors that can't adapt quickly enough. The opportunity is that you can potentially reduce software spending by replacing some traditional software with AI agents, and you can negotiate better terms with vendors who are facing structural pressure.

The era of predictable, boring software stability is gone. That's disruptive and uncomfortable for everyone. But it also creates genuine opportunities for companies, investors, and buyers who recognize the shift and adapt accordingly. The winners in the next era won't be those who hang on to stable-era assumptions. They'll be those who design explicitly for an AI-first, instability-embracing world.

FAQ

What specifically changed in June 2024 that made AI a real threat to SaaS companies?

Claude 3.5 Sonnet's release marked the moment when large language models became genuinely capable of performing complex autonomous work—particularly code generation—at production quality. Before this release, AI coding assistants existed but required significant human oversight and revision. After Claude 3.5 Sonnet, developers could describe what they wanted to build and have the AI generate production-ready code with minimal or no human revision. This capability threshold transformed AI from an interesting feature into a replacement layer for entire categories of work that software previously just organized or facilitated, which is fundamentally different from previous software innovations.

Why is per-seat pricing no longer viable for enterprise software companies?

Per-seat pricing only works when seats directly correlate with work being performed. If an AI agent can handle the work of five sales development representatives, a company no longer needs five licenses for their sales tools—they need one. The vendor's revenue automatically declines even though the customer is using the software more effectively. This creates an impossible situation: the more successfully your customers adopt AI to reduce headcount, the more your revenue declines. Switching to outcome-based pricing or usage-based pricing doesn't solve the problem because customers resist these models and investors hate their unpredictability, but staying with per-seat pricing means accepting declining revenue as customers optimize their headcount.

How are large SaaS leaders like Salesforce and Workday acknowledging the threat without admitting defeat?

Executives use careful language evolution on earnings calls to gradually reframe the threat without explicitly admitting to business model breakdown. For example, they shift from admitting "customers are committing to lower headcount" to claiming "AI concerns are overblown" to pivoting metrics from "total seats" to "revenue per seat" (which can remain flat even as seat count declines if pricing increases). They also emphasize their AI investments as if adding AI features solves the fundamental problem of their core business model being disrupted. Marc Benioff at Salesforce was more direct, explicitly stating he reduced headcount from 9,000 to 5,000 "because I need less heads," but even that transparency is somewhat unusual. Most executives use carefully calibrated language to acknowledge threat without admitting their business model is under pressure.

What's the difference between AI as a feature and AI as a replacement layer, and why does it matter?

When AI is a feature, it makes humans 10-20% more efficient at work they were already doing. A CRM with AI-powered lead scoring still requires humans to follow up on leads; it just helps them prioritize better. This fits into traditional software business models and doesn't require fundamental changes to pricing or strategy. When AI is a replacement layer, it performs 70-80% of the work autonomously, with humans handling only the remaining 20%. This requires fundamentally different product architecture, different pricing models, different workflows, and different competitive dynamics. It's not an enhancement to existing software—it's a category redefinition. Most executives and investors are treating AI as a feature when it's increasingly functioning as a replacement layer.

Which SaaS categories are most exposed to disruption from AI, and which are more defensible?

Categories most exposed include horizontal workflow software (project management, task routing), CRM and sales engagement (AI can handle prospecting and qualification), customer support (AI can handle 80% of inquiries), accounting (AI can generate reports and reconcile accounts), and knowledge management (AI can provide answers without requiring humans to search). Categories that might be more defensible include vertical solutions owning specific industry workflows, infrastructure software enabling AI adoption, platforms with strong domain-specific data and expertise, and solutions that make it easy for customers to integrate AI into their existing processes. The pattern is: horizontal software solving generic problems is more exposed; vertical software, infrastructure, and domain-specific solutions are more defensible.

How should enterprise software buyers think about vendor risk in an unstable market?

Buyers should explicitly evaluate whether vendors are acknowledging and planning for AI disruption of their business model, or whether they're treating AI as just another feature to add. Ask vendors directly: what is your strategy when AI systems are doing much of the work that currently justifies your per-seat pricing model? Do they have credible answers? Also evaluate whether the vendor's competitive moat is based on switching costs that might be eroded by AI abstraction layers (bad sign for vendor resilience) or on genuine domain expertise and defensible data (better sign). Finally, consider whether negotiating outcome-based pricing or reducing software spend by replacing some functionality with AI agents might actually reduce your risk even as it increases your technical complexity. In an era of vendor instability, reducing dependence on any single vendor might be strategically wise.

What's the most likely enterprise software landscape in 2027-2028, and how different will it be from today?

The likely landscape involves consolidation among vendors without specific defensibility (many marginal players will be acquired or fail), moderation of growth for broad horizontal platforms (they'll remain important but won't be the growth engines they were), acceleration of vertical and domain-specific solutions (higher growth, more defensibility), and an explosion of infrastructure companies supporting AI adoption (tools for AI governance, monitoring, integration, and orchestration). Pricing models will be more diverse and less standardized. The predictable, per-seat-driven model that dominated the 2010s and 2020s will be replaced by more varied models depending on how AI is being used. The biggest change won't be in specific products but in the underlying assumptions: companies can no longer plan multi-year roadmaps with confidence, assume per-seat pricing will work, or expect customer expansion without explicitly addressing how AI adoption affects unit economics.

Should I be building a new SaaS company in this environment, or is it too risky?

Building SaaS is not inherently riskier now, but it requires different optimization targets. Don't try to build horizontal platforms—that space is increasingly commoditized and exposed to AI disruption. Do build vertical solutions owning specific workflows or industries, infrastructure supporting AI adoption, or platforms explicitly designed for AI integration from day one. Optimize for quick adaptation and short planning cycles rather than multi-year roadmaps. Build with AI integration as a core design principle, not an afterthought. Consider whether your solution should be operated by AI agents or coordinating with AI agents, not just used by humans. The companies that will be most successful are those explicitly designing for an AI-first world rather than treating AI as an addition to a traditional software business model.

How are companies like Klarna that are rebuilding enterprise functionality around AI agents actually threatening traditional vendors?

Klarna's CEO stated that with AI agents and AI engineers becoming proficient, "you can rebuild most enterprise SaaS functionality, host for super cheap, and get basically 90%+ functionality." This represents a fundamental threat because it suggests that traditional vendor differentiation (complex features, integrations, polish) might not matter if an AI-native alternative can achieve 90% of the functionality at a fraction of the cost. Klarna isn't trying to be better Salesforce; it's trying to solve the same underlying business problems using fundamentally different architecture and economics. Most enterprises aren't doing this yet (Klarna is still somewhat of an outlier), but if this approach works at scale, it collapses the economics for traditional vendors. The threat isn't that a competitor builds better CRM software—it's that nobody needs CRM software anymore if an AI system can handle customer relationship management with simpler infrastructure and lower cost.

What concrete steps should SaaS leaders take immediately to prepare for continued instability?

First, acknowledge the threat honestly internally and commit resources to exploring AI-native alternatives to your existing business model—not just adding AI features but fundamentally rethinking what value you provide as AI systems get more capable. Second, streamline decision-making and compress planning cycles from 3-year roadmaps to quarterly reassessment. Third, build capability to move resources quickly between initiatives based on new information about what's working. Fourth, prepare customers and investors for pricing model evolution—don't wait for crisis to discuss alternatives to per-seat pricing. Fifth, consider disrupting parts of your own business before external competitors do. Sixth, build infrastructure and managed services around AI adoption so you're supporting customers' transition rather than fighting it. Seventh, evaluate your competitive moats honestly: do they disappear if AI systems can abstract away your interface or reduce headcount? If so, start building different defensibility immediately.

Key Takeaways

- SaaS stability era (2010-2024) is completely over—disrupted by AI capabilities crossing critical thresholds in June 2024 when Claude 3.5 Sonnet enabled autonomous work at production quality

- Per-seat pricing, the foundational SaaS business model, breaks when AI reduces headcount—vendors face impossible choice between accepting declining revenue or switching to unpredictable models investors hate

- Traditional competitive moats (data gravity, switching costs) are eroding as AI abstraction layers can sit atop any system of record, making vendor lock-in less relevant

- Public market repricing in January 2026 was late acknowledgment of threat builders recognized 6+ months earlier—executives are adjusting narratives in real-time on earnings calls rather than confronting fundamental issues

- Horizontal workflow software faces maximum disruption (80% of value disappears if 80% of routed work becomes AI-autonomous), while vertical solutions with domain expertise and infrastructure plays remain relatively defensible

- Three-year product roadmaps are obsolete; effective planning requires quarterly reassessment because fundamental category threats can emerge in months, not years

- Winners will be companies explicitly designed for AI-first world (infrastructure supporting AI adoption, vertical solutions owning specific workflows) not those retrofitting AI onto legacy architectures

- Enterprise buyers should evaluate vendor resilience by asking about credible strategies when AI does work that currently justifies per-seat pricing, and consider reducing software spend by replacing some functionality with AI agents

- Consolidation is inevitable among marginal vendors without defensibility; infrastructure companies supporting AI adoption will likely outperform horizontal platforms trying to maintain traditional per-seat models

Related Articles

- The AI Agent 90/10 Rule: When to Build vs Buy SaaS [2025]

- Amazon Officially Dethroned Walmart as America's Largest Company [2025]

- The OpenAI Mafia: 18 Startups Founded by Alumni [2025]

- Joseph C. Belden Innovation Award 2026: Complete Guide to Winning Scaling Perks [2026]

- The AI Productivity Paradox: Why 89% of Firms See No Real Benefit [2025]

- AI Defense Weapons: How Autonomous Drones Are Reshaping Military Tech [2025]

![SaaS Instability: How AI Is Redefining Enterprise Software [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/saas-instability-how-ai-is-redefining-enterprise-software-20/image-1-1771688256054.jpg)