PC Market Downturn: How AI's Memory Crunch Will Impact 2026

There's a war happening inside the semiconductor industry, and PC buyers are going to lose.

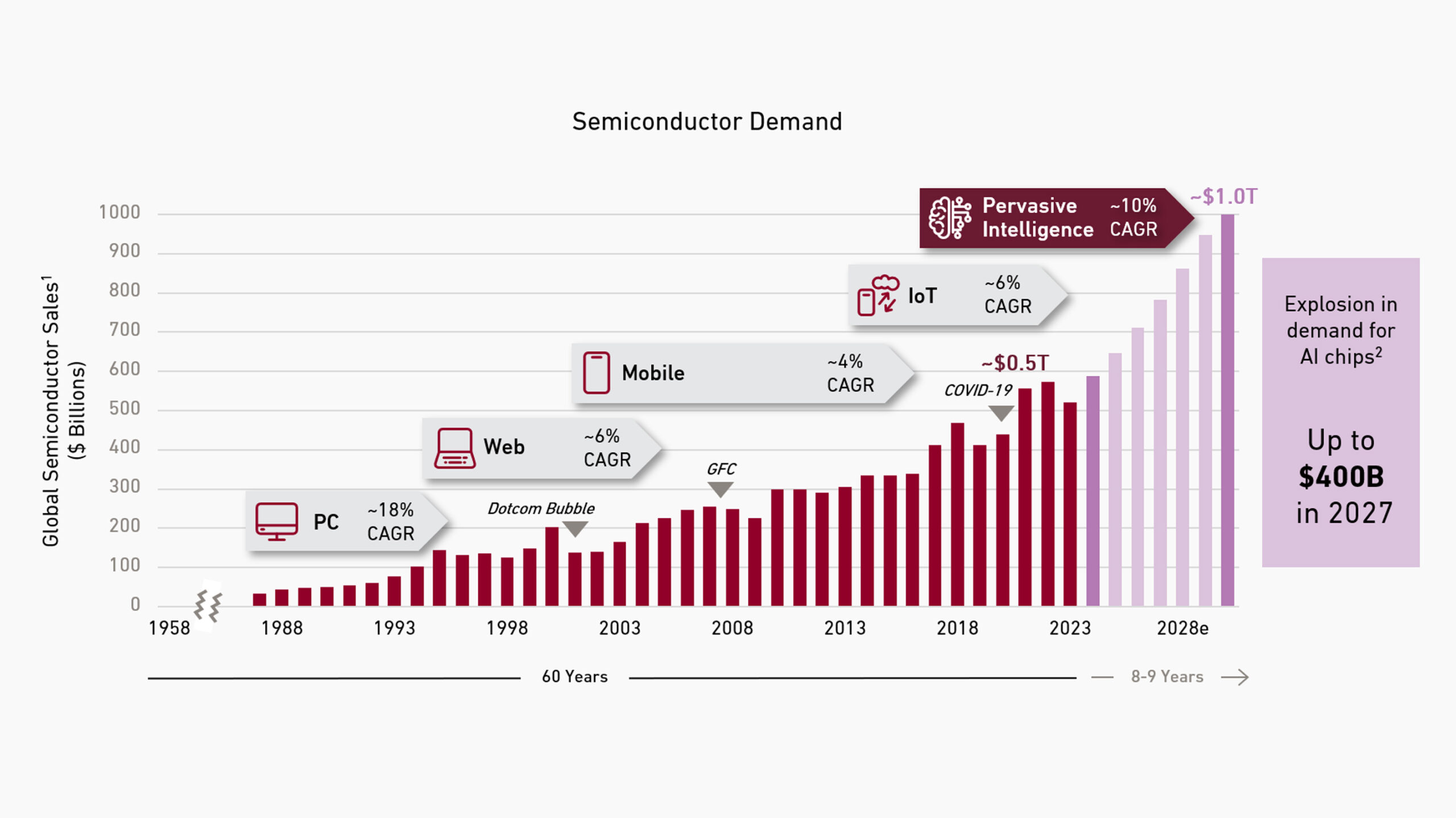

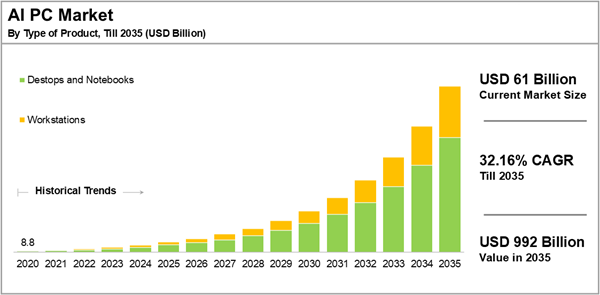

The stakes couldn't be clearer: the explosive growth of artificial intelligence is sucking up the world's memory production capacity, leaving traditional consumer electronics scrambling for scraps. Meanwhile, computers that were supposed to save the PC industry—AI-equipped machines with built-in neural processors—are ironically becoming more vulnerable to the very dynamics crushing the market they're meant to revitalize.

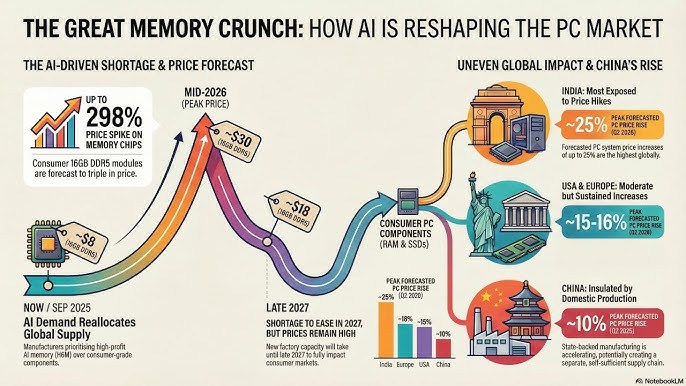

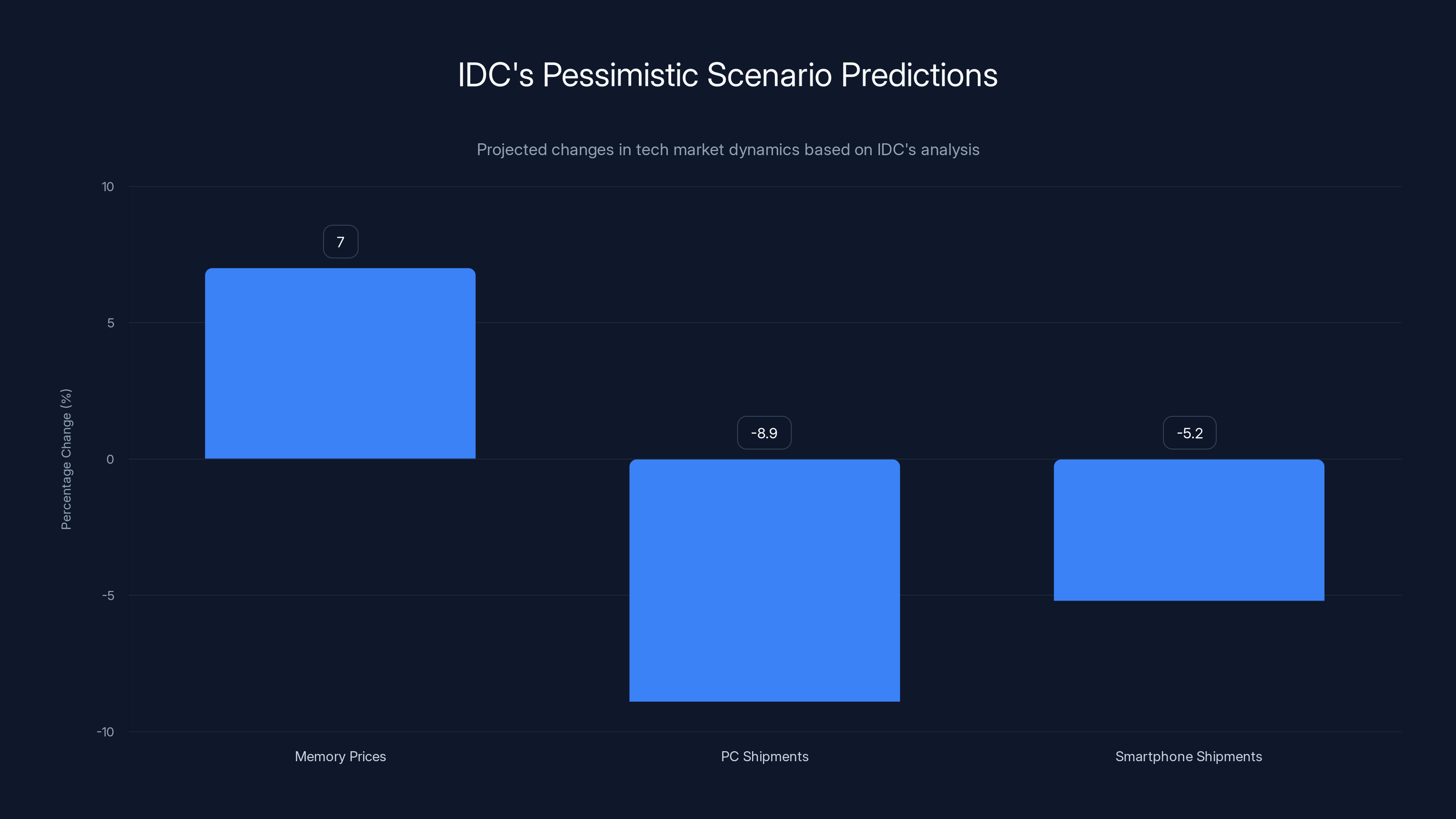

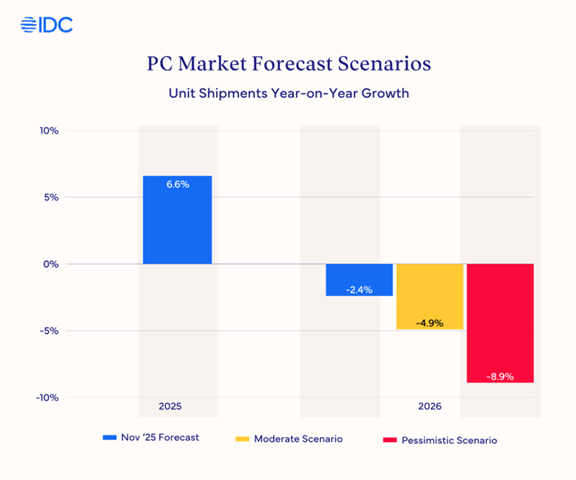

This isn't speculation or industry gossip. The International Data Corporation, one of the world's most influential technology forecasters, has published a comprehensive analysis warning that the PC market faces a genuine crisis in 2026. Their worst-case scenario predicts PC shipments could shrink by 8.9 percent, prices could jump 6 to 8 percent, and the entire consumer electronics ecosystem could suffer similar damage.

The culprit? Memory makers have abandoned the consumer market almost entirely, redirecting their production toward high-bandwidth memory (HBM) and specialized DDR5 chips that fuel AI data center infrastructure. When you stop making affordable RAM for PCs and smartphones, prices don't stay flat—they explode. And when prices explode, consumers stop buying.

Let's break down what's really happening, why it matters, and what it means for you as a consumer, tech professional, or industry observer.

The Perfect Storm: AI's Insatiable Memory Appetite

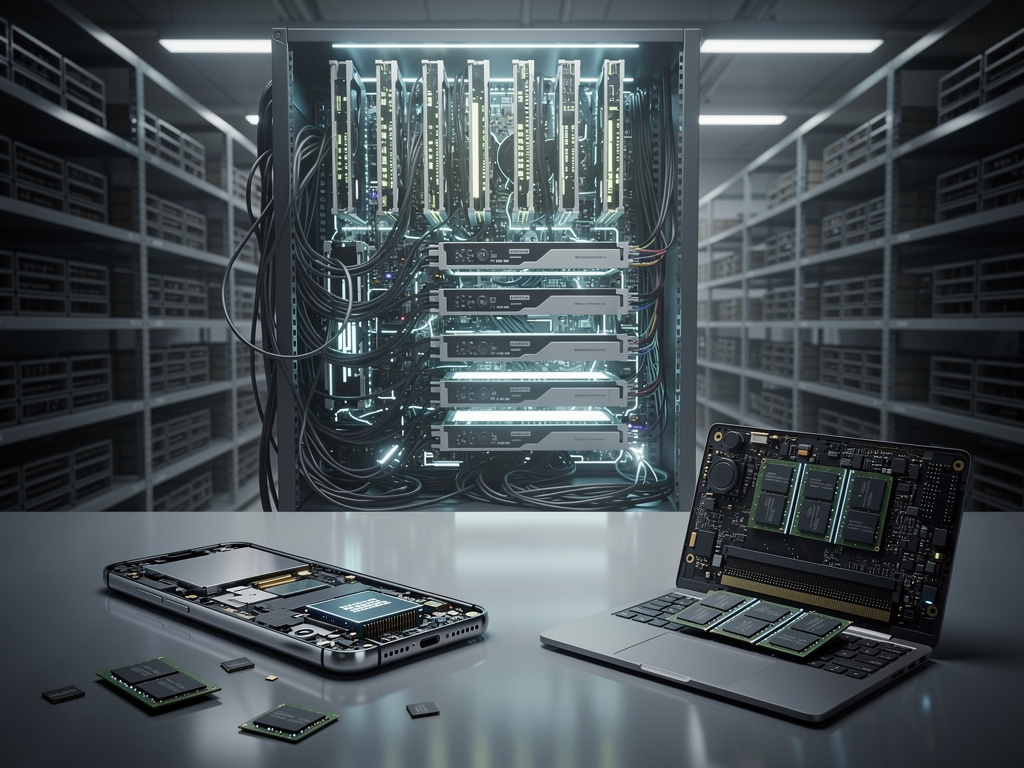

Understand this first: memory doesn't grow on trees. DRAM and NAND flash memory are manufactured in specialized fabs, and those fabs have finite capacity. Every wafer of silicon sent to produce HBM for data centers is a wafer not producing consumer-grade RAM.

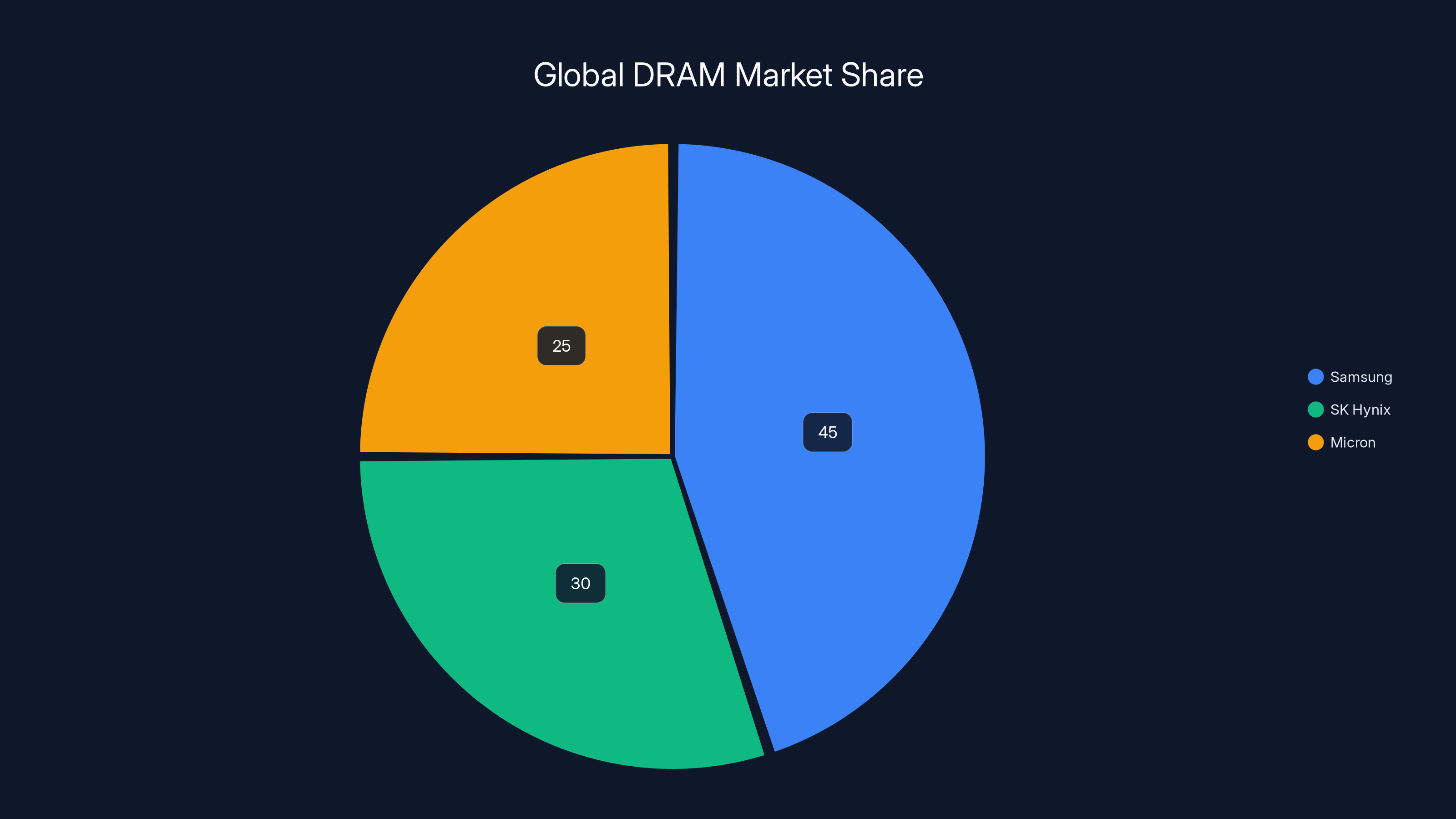

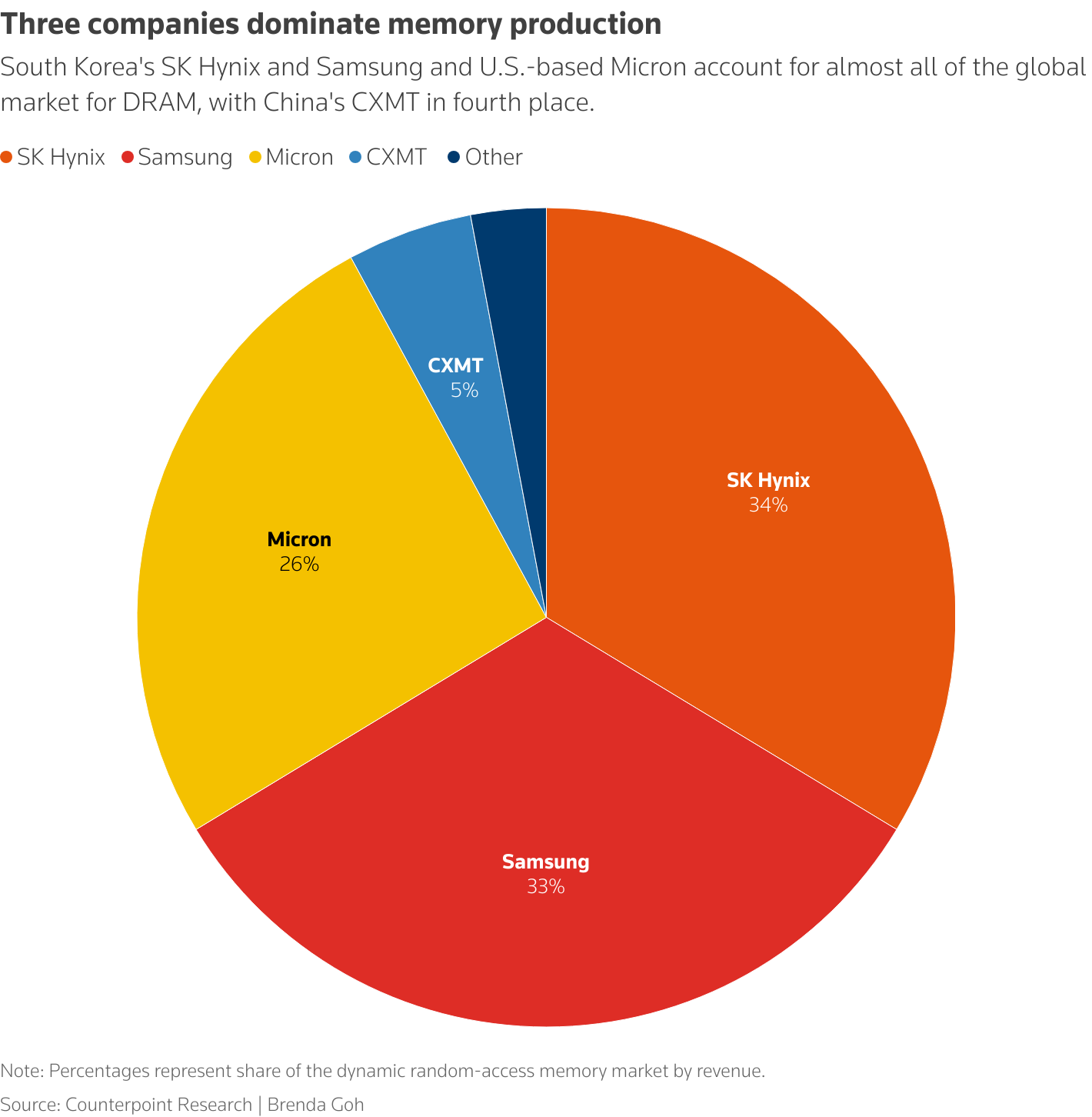

The numbers tell the story. According to industry analysis, major memory manufacturers including Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron have shifted their strategic focus almost entirely toward AI infrastructure. They're not doing this out of charity—AI data centers are the most profitable segment in the semiconductor industry right now, and margins are extraordinary.

Here's the thing: when you're running a multi-billion dollar manufacturing operation, you chase revenue and profit. AI infrastructure pays better than consumer electronics, full stop. A single hyperscaler like Meta, Google, or OpenAI is worth more revenue than dozens of traditional PC companies combined. So the math is obvious.

The result is what economists call "production reallocation." Memory fabs that traditionally split capacity 60% consumer and 40% data center have inverted those ratios. Some facilities have gone nearly 100% AI-focused. This isn't temporary—these are strategic, long-term commitments backed by tens of billions in capital investment.

The consumer market didn't disappear. The available supply of consumer-grade RAM just evaporated.

What's particularly brutal is the timing. The PC industry spent the last two years recovering from a post-pandemic slump that left inventories bloated and demand depressed. Companies were finally starting to gain momentum again, with modest shipment growth predicted for 2025. Then the memory crunch hits.

IDC predicts a 6-8% price increase for PCs and smartphones by 2026 due to memory supply shifts. Estimated data.

Why PC Makers Can't Just Switch Suppliers

You might think this is simple: if Samsung stops making consumer RAM, PC makers buy from someone else. Except that's not how the semiconductor industry works.

There are only three meaningful global manufacturers of DRAM: Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron. There's no fourth option, no emerging competitor ready to step in and save the day. These companies operate massive, capital-intensive fabs that take years to build and cost billions to construct. You can't just snap your fingers and create new capacity.

Moreover, all three major manufacturers are making the same strategic choice—pivot toward AI. This isn't a secret conspiracy. It's logical profit-maximization. The incentives are aligned across the entire industry, which means there's no competitive pressure forcing any player to maintain consumer market share.

PC makers face a terrible choice: accept dramatically higher RAM costs and pass them to consumers, or reduce the RAM in their machines and watch performance suffer. Spoiler alert: they're choosing the first option.

Framework, the modular PC company known for repairability and customization, has already had to raise prices on multiple SKUs. They've publicly stated that further increases are "highly likely over the next months." If Framework—a company with direct relationships with memory suppliers and flexible pricing structures—is scrambling, you can bet larger OEMs like Dell, HP, and Lenovo are facing even more pressure.

The supply chain dynamics compound the problem. Most PC makers operate on razor-thin margins—typically 3 to 7 percent. A sudden 20 to 30 percent jump in DRAM costs doesn't disappear. It transfers directly to end consumers.

Estimated data shows that midrange and budget smartphone makers face higher impact from RAM cost increases, with each experiencing around 40% impact, compared to 20% for high-end manufacturers.

The Great Irony: AI PCs Hit Hardest

This is where the story gets darkly funny.

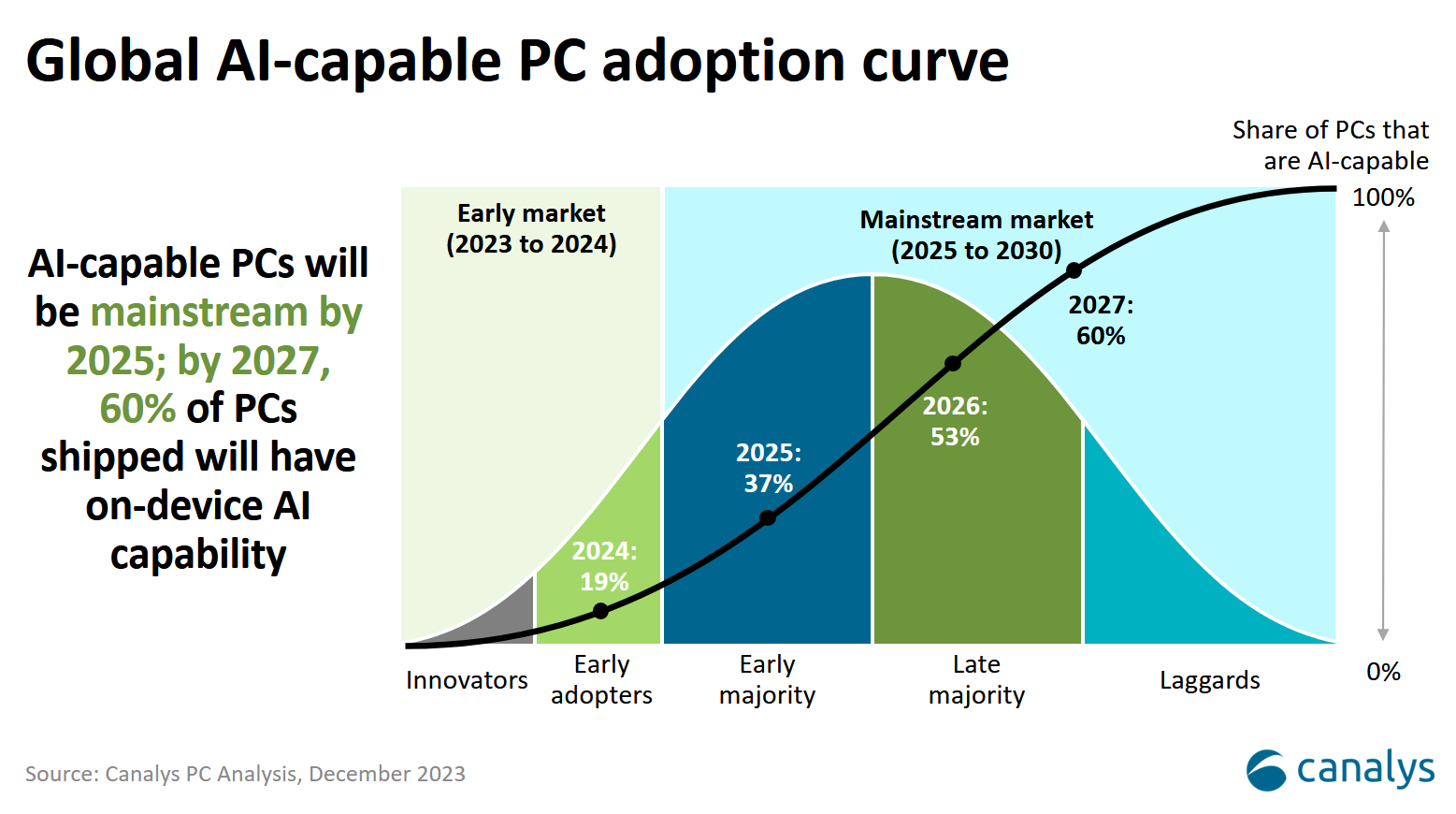

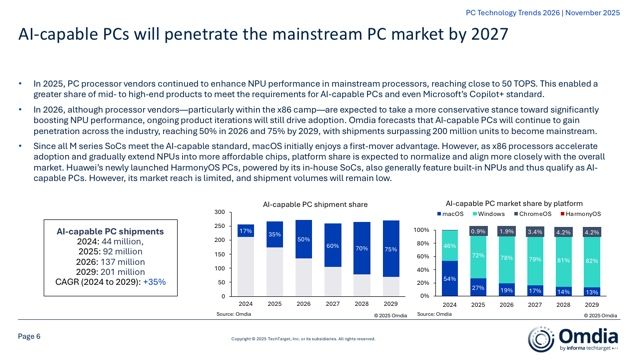

The entire PC industry spent 2024 and 2025 selling the "AI PC" narrative—computers with dedicated neural processing units like Qualcomm's Snapdragon X or Intel's Core Ultra with AI accelerators. These machines promised to run AI models locally, protecting privacy, enabling offline functionality, and revolutionizing how consumers interact with their computers.

Intel, Qualcomm, AMD, and the major OEMs all committed massive resources to this transition. AMD's Ryzen AI processors, Intel's AI Boost architecture, and Qualcomm's NPUs represent billions in R&D investment. The bet was simple: AI PCs would reignite PC demand after years of stagnation.

Except AI PCs need more RAM than traditional machines. Running large language models locally, maintaining AI context windows, and supporting multiple AI tasks simultaneously all demand significantly higher memory capacity. An AI-capable laptop might ship with 16 or 32 GB of LPDDR5X—versus the 8 or 16 GB in traditional machines.

More RAM means more vulnerability to the memory crunch. The very feature that was supposed to save the PC industry becomes a liability when RAM costs spike.

It's like designing a sports car just as gasoline prices quadruple. The engineering is sound, but the economics become impossible.

The tragedy is that AI PCs still represent genuine consumer value. They enable real use cases: image generation without cloud services, advanced voice recognition, privacy-preserving assistant features, and local document analysis. But if those machines cost 20 to 30 percent more than a traditional laptop, consumer adoption stalls.

Smartphone Market: Collateral Damage

PC makers aren't the only victims. The smartphone industry faces identical dynamics.

The IDC's analysis predicts smartphone shipments could shrink by 5.2 percent in their worst-case scenario, with average selling prices climbing 6 to 8 percent. For context, that's a significant contraction in a market that ships over 1.2 billion units annually.

Smartphone makers rely on slightly different memory (they use LPDDR instead of DDR5), but the underlying competition for fab capacity is identical. When Samsung and SK Hynix allocate their best facilities to HBM production, everything else gets deprioritized—including smartphone DRAM.

The impact is uneven, though. Apple and Samsung, with massive cash reserves and long-term supply agreements negotiated years ago, can likely absorb higher RAM costs and maintain pricing discipline. A 16 GB iPhone with slightly higher memory costs? Apple will just fold that into their normal margin structure.

Midrange and budget smartphone makers don't have that flexibility. They operate on thin margins and don't have supply agreements locking in old pricing. A $200-400 smartphone maker might need to cut 2 GB of RAM or accept 30 percent lower margins.

Lower RAM means reduced performance, fewer simultaneous background applications, and less smooth multitasking. It directly harms the consumer experience, particularly in emerging markets where budget phones dominate.

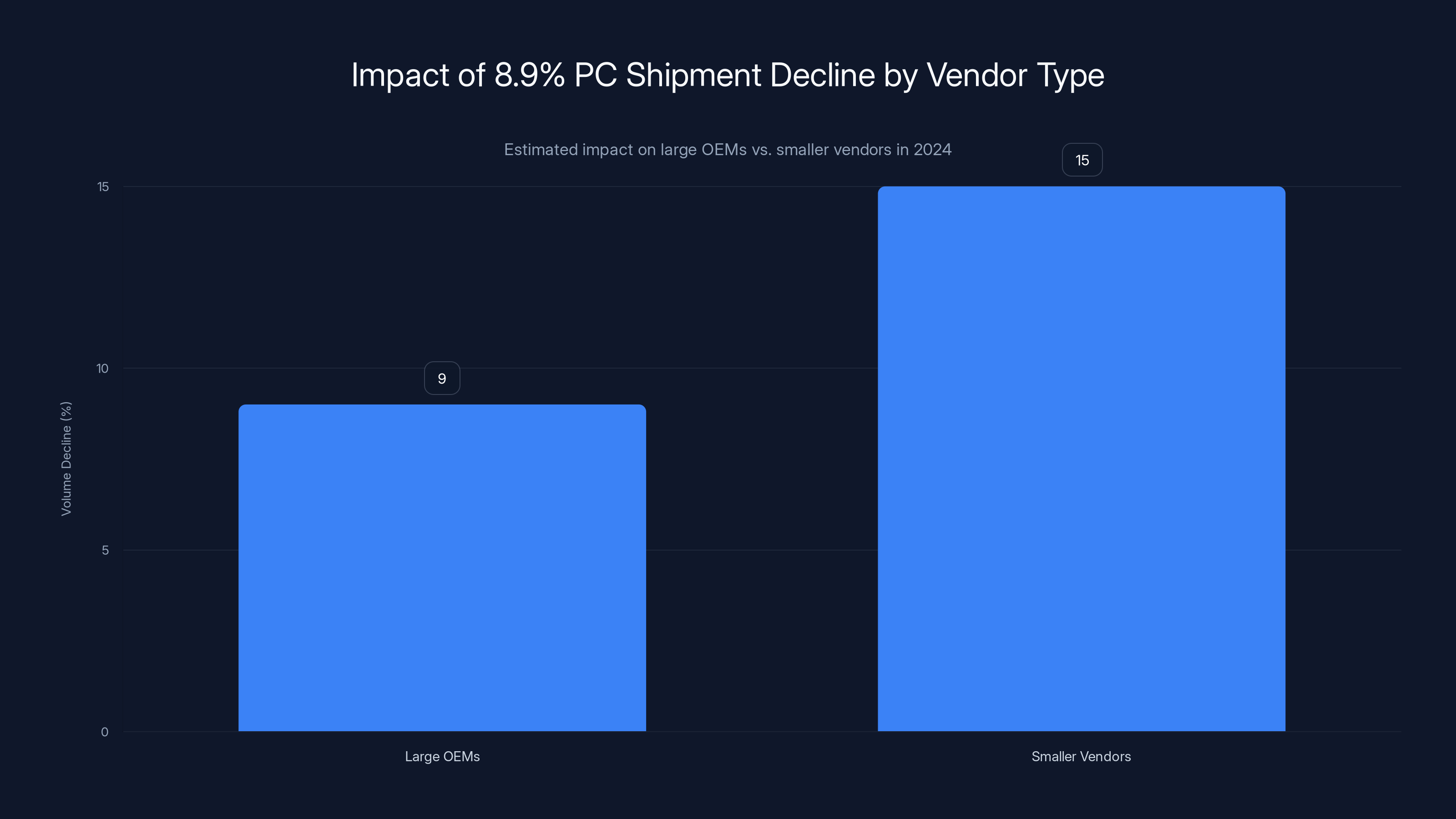

Large OEMs are expected to see a volume decline of 9%, while smaller vendors might face a 15% decline due to lack of supply agreements. Estimated data.

The Death of a RAM Brand

This isn't theoretical speculation about potential futures. The memory crunch has already claimed a victim: Crucial's consumer DRAM brand.

Crucial, owned by Micron, was one of the few consumer-facing RAM manufacturers. They sold DDR4 and DDR5 directly to PC builders, enthusiasts, and system integrators who wanted alternatives to Corsair, Kingston, and other larger players. Their products were solid, reasonably priced, and widely available.

In 2025, Micron discontinued Crucial's consumer DRAM line.

Official statements blamed "market consolidation" and "focusing on growth segments," which is corporate-speak for "we make more money selling HBM to data centers." But the real message is stark: if you're a memory manufacturer, the consumer market is becoming too small and unprofitable to justify production capacity.

Crucial's discontinuation is a canary in the coal mine. It's the market telling you, explicitly, that consumer memory is deprioritized. When a company as large as Micron decides consumer RAM isn't worth their time, you know supply dynamics are genuinely broken.

This matters because it reduces options for PC builders. Fewer suppliers means less competitive pressure on pricing. Kingston and Corsair now face even less competition, which is bad news for anyone buying new RAM in 2026.

IDC's Pessimistic Scenario Explained

Let's examine the IDC's methodology and assumptions, because this report is generating significant industry discussion.

The International Data Corporation, one of the world's most trusted technology research firms, conducted their analysis across three scenarios: optimistic, base case, and pessimistic. The pessimistic scenario isn't fiction—it's based on realistic assumptions about market dynamics and supply constraints.

Here's what IDC assumes in their worst-case model:

Memory availability remains constrained: HBM and data center DRAM production continues to dominate memory fab allocation, with consumer DRAM remaining scarce. This assumption is reasonable given current capital expenditure plans from Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron through 2026-2027.

Prices rise 6-8 percent: This reflects a realistic cost increase given reduced supply. It's not a 50 percent spike (which would be catastrophic), but it's meaningful enough to impact consumer behavior. Historical DRAM price cycles suggest 6-8 percent annual increases are on the extreme end but not impossible.

PC shipments fall 8.9 percent: This is the controversial prediction. The IDC assumes that price-sensitive consumers will delay purchases when they see 15-20 percent more expensive laptops. They won't switch to tablets or other devices—they'll just wait.

Smartphone shipments fall 5.2 percent: Similar logic, but the impact is somewhat muted because phones have more captive demand and less price sensitivity.

The IDC's methodology isn't alarmist. They're not predicting industry collapse. They're predicting a demand contraction of the same magnitude that occurred during previous tech cycles—meaningful but not catastrophic.

What makes this analysis credible is that the IDC isn't a doomsday outfit. They predict growth in most tech categories. They're known for measured, realistic forecasts. When they issue a warning, the industry listens.

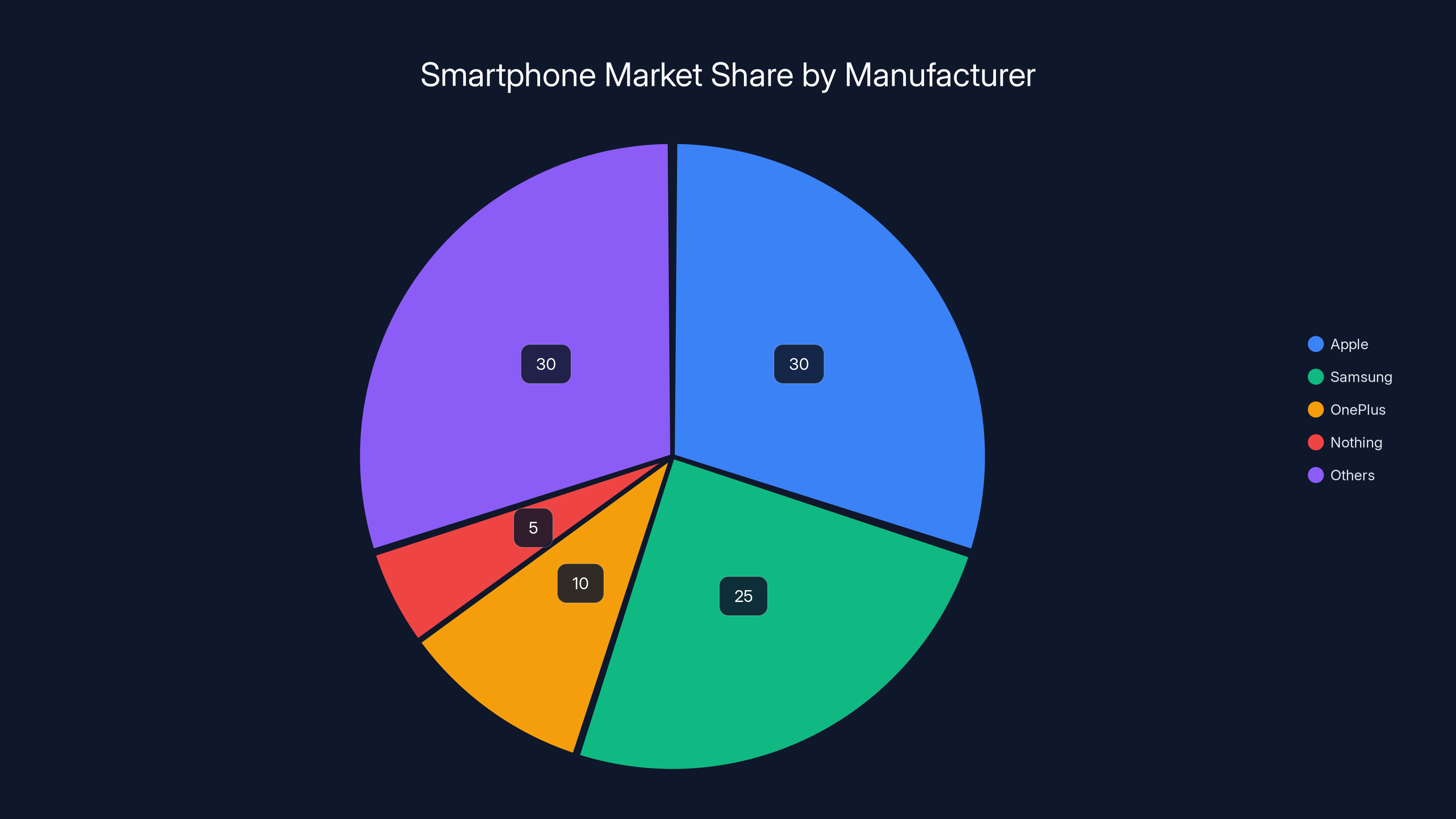

Estimated data shows Apple and Samsung dominate the smartphone market, while smaller manufacturers like OnePlus and Nothing face increased margin pressure due to rising costs.

Memory Manufacturers: Following the Profit

You can't blame memory manufacturers for their strategic choices. They're operating rationally within market incentives.

Consider the return on capital. A DRAM fab producing consumer-grade DDR5 might generate 15-20 percent gross margins. The same fab producing HBM for AI accelerators might generate 40-50 percent margins, possibly higher. When you're managing billions in capital investment, that margin difference is enormous.

A simplified calculation: A fab costs

Moreover, AI infrastructure demand is growing exponentially while consumer PC demand is flat or slightly declining. A rational manufacturer allocates capital toward the growing, high-margin segment. They're not being greedy—they're being mathematically correct.

The problem is that rational individual behavior creates irrational collective outcomes. When every memory manufacturer makes the same rational choice, the result is a consumer memory shortage that harms the broader economy.

This is a classic market failure. The memory market doesn't have the price elasticity to correct itself quickly. Consumers can't just "buy more smartphones" at higher prices—they have budget constraints. The market doesn't automatically rebalance toward equilibrium.

Price Increases: How Much, Exactly?

The IDC's 6-8 percent prediction is the headline number, but let's dig deeper into what this means in real dollars.

A typical gaming laptop with 32 GB of DDR5 SDRAM might have

When BOM costs rise faster than expected, manufacturers face a choice:

- Absorb the cost and reduce margins (not viable for most OEMs)

- Reduce specifications (use less RAM, slower DRAM) and maintain retail prices

- Pass the cost to consumers through price increases

Most manufacturers will do a combination of all three. Some laptop models might drop from 16 GB to 12 GB RAM. Others might stay at 16 GB but cost $100 more. Flagship models might see price increases while budget models get specification reductions.

Framework's price increases ranged from

Consumers notice

IDC's pessimistic scenario predicts a 7% increase in memory prices, an 8.9% decrease in PC shipments, and a 5.2% decrease in smartphone shipments. Estimated data based on IDC's assumptions.

Market Contraction: What 8.9% Really Means

Let's contextualize the 8.9 percent PC shipment decline IDC predicts.

Global PC shipments in 2024 were approximately 260-270 million units. An 8.9 percent decline means roughly 23-24 million fewer PCs sold. That's a market worth tens of billions of dollars in revenue.

For context:

- A 5 percent decline represents a typical recession-year contraction

- An 8.9 percent decline is comparable to 2023's post-pandemic downturn

- Double-digit declines are apocalyptic events (2009 financial crisis territory)

So the IDC is predicting a serious contraction but not total collapse. It's "bad business cycle" not "industry emergency."

However, the impact varies dramatically by vendor. Large OEMs like Dell, HP, and Lenovo have the supply agreements and market power to navigate the crisis. They might see volumes decline 8-10 percent but maintain profitability through price increases.

Smaller vendors get crushed. Companies that don't have long-term memory supply agreements face catastrophic cost increases. Think of regional Asian brands, white-label builders, and smaller startups. Many will exit the market or dramatically reduce product lines.

Some segments are more vulnerable than others. Gaming laptops, which require high-capacity VRAM, face steeper cost increases than budget office machines. Workstation manufacturers face similar challenges. Consumer brands that compete on price suffer more than those competing on performance or brand prestige.

Why 2026 Specifically?

You might ask: why does the memory crunch peak in 2026? Why not 2025 or 2027?

The answer involves supply cycles and capital expenditure timelines. Current fab capacity constraints are already visible in late 2024 and 2025. But memory price increases take time to filter through the supply chain. Manufacturers with long-term contracts won't see price increases immediately. They'll hit when contracts renew—typically in Q1 and Q3.

Most PC contracts renew in early 2026, which is when accumulated memory cost increases suddenly become binding constraints. Additionally, AI demand continues accelerating through early 2026. Hyperscalers are still ramping data center buildouts, continuing to pull capacity away from consumer markets.

By late 2026, some new capacity comes online. Memory fabs that broke ground on new facilities in 2022-2023 start producing at scale. Supply loosens incrementally. 2027 should see further capacity additions as Samsung, SK Hynix, and others complete planned expansions.

But in 2026—the sweet spot between maximum demand contraction and supply relief—conditions are worst. It's a specific moment in time when market forces align to create maximum pain.

Some analysts argue the crunch could be worse or better depending on how AI infrastructure demand evolves. If hyperscalers pull back on data center investment (highly unlikely), supply pressure eases. If they accelerate spending (quite possible), the crunch intensifies.

Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron dominate the DRAM market, leaving PC makers with limited supplier options. Estimated data.

Who Survives: Big OEMs vs. Small Players

The market contraction will be uneven, and understanding the distribution is crucial.

Large OEMs (Dell, HP, Lenovo, Apple, Samsung): These companies will survive and likely prosper. They have negotiating power with memory suppliers. They can secure long-term contracts, lock in pricing, or commit to volume minimums in exchange for favorable rates. They have fat enough margins to absorb cost increases temporarily. Their brand power insulates them from price-sensitive competition.

What might suffer is their product portfolio. Budget lines might get canceled. They might be more aggressive with price increases, knowing consumers have fewer alternatives. But Dell isn't going out of business because DRAM costs rise.

Mid-market brands (ASUS, Acer, MSI): These companies have decent market position but less negotiating power than the tier-1 vendors. They'll feel the crunch more acutely. Some models will be canceled. Others will see significant price increases. Margins compress as they can't fully pass costs to consumers. Some will exit certain segments entirely.

Niche players (Framework, Purism, System 76, gaming specialists): These companies operate with modest margins and less negotiating power. They're already raising prices (Framework is living proof). Many will likely reduce product SKUs, focus on high-margin segments, or make strategic exits from certain markets.

Framework's public statements about future price increases suggest they're already planning significant changes to their product line, pricing, or both. They might shift toward higher-end configurable machines where the percentage impact is less noticeable, or they might retreat from certain market segments.

Budget brands in emerging markets: This is the tragedy. Chinese brands like Realme, Indian brands like Micromax, and other emerging market players depend on thin margins and volume sales. They can't absorb memory cost increases, can't pass them to price-sensitive consumers, and have minimal negotiating power with suppliers.

These companies will either retreat upmarket (directly competing with brands they weren't competing with before) or reduce unit volume dramatically. For consumers in emerging markets, this means fewer affordable laptop options.

The Smartphone Market: Different Dynamics, Similar Pain

While PC makers face existential challenges, smartphone manufacturers operate in a different context.

Smartphones have more inelastic demand. People replace phones every 3-4 years out of necessity, not choice. A $100 price increase hurts, but many consumers will accept it. Additionally, smartphone makers have more flexibility in specification reduction—you can ship a phone with 8 GB instead of 12 GB without catastrophic performance degradation.

However, the memory cost issue is real. LPDDR5 and LPDDR6 production faces the same constraints as DDR5—capacity is limited, and data center demands are pulling attention toward specialized AI memory.

Bigger issue: flagship phones require more memory. Phones claiming "AI capabilities" (Apple, Samsung, Google) need sufficient RAM to run on-device models. The same dynamic that hits AI PCs hits AI phones: the feature that was supposed to drive the market becomes a cost liability.

Apple will raise iPhone prices by $50-100 and most customers will accept it. Samsung will do similar moves. Smaller manufacturers will get stuck. OnePlus, Nothing, and other challengers will see margin pressure intensify.

The 5.2 percent shipment decline IDC predicts is the market adjusting to higher prices. Some consumers will stretch their replacement cycles. Others will trade down to older models or mid-range devices. The total market shrinks.

What About the Enterprise Market?

One often-overlooked angle: how do business desktops and workstations handle the memory crunch?

Business customers have different priorities. They care about reliability, support, and total cost of ownership—not whether their laptop is 10 percent cheaper. They're willing to pay for stability and long-term supply certainty. Enterprises with large deployments will negotiate multi-year contracts with PC makers, who will in turn secure memory supply through long-term arrangements with manufacturers.

In other words, the enterprise market insulates itself from the worst of the crunch through contractual arrangements. A Fortune 500 company buying 50,000 laptops for workforce refresh will have locked-in pricing and guaranteed supply. They won't face the volatility affecting consumer and SMB markets.

This might actually accelerate a trend: increased market share for enterprise-focused vendors at the expense of consumer brands. Corporations get stability. Consumers get disruption. The market bifurcates further.

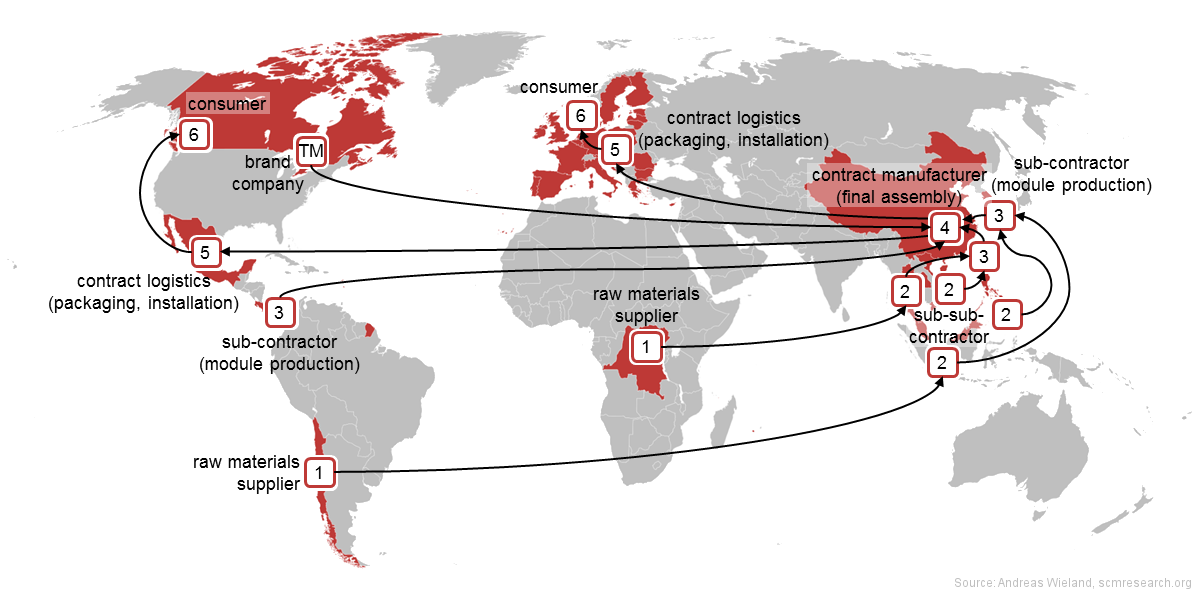

Supply Chain Ripple Effects

Here's where it gets interesting: the memory crunch ripples through adjacent industries.

Monitor manufacturers: Monitor prices have already started rising due to scarcity of DRAM (used in monitor scalers). As PC prices rise and demand contracts, monitor demand contracts similarly. Smaller monitor makers will struggle.

Accessory markets: Keyboard, mouse, and peripheral vendors depend on volume sales. Lower PC volumes mean lower accessory sales. Some specialist manufacturers (mechanical keyboard makers, high-end mouse producers) are less affected. Commodity accessory makers get crushed.

Repair and refurbishment markets: When new PC prices spike, older used machines become more valuable. Secondary markets heat up. Companies like Backmarket and Cashify might see increased activity as consumers seek affordable alternatives. This cannibalization cuts into new device sales even more.

Trade-in economics: Retailers relying on device trade-in programs might see those programs become less profitable. If used laptops are worth more, retailers pay more for them, cutting into margins.

The contraction doesn't stay isolated to memory or PC makers. It propagates through entire ecosystems.

Geographic and Regional Variation

The memory crunch will be experienced differently around the world.

North America and Western Europe: These regions have strong corporate demand, PC replacement cycles driven by business needs, and consumers with substitution options (tablets, chromebooks, used devices). The market contracts but doesn't collapse. Price increases are painful but manageable.

Emerging Asia (India, Southeast Asia, parts of China): These regions depend heavily on affordable new devices. PC penetration is still climbing—many households are buying their first laptop. When prices rise 20-30 percent, purchase decisions get delayed indefinitely. Market contraction is severe. Education sectors suffer (laptops for students become unaffordable). Tech skill development gets impacted.

East Asia (Japan, South Korea, Taiwan): These mature markets have sophisticated enterprise sectors and strong refurbishment ecosystems. Official new device sales fall, but used/refurbished markets boom. Overall impact is moderated.

The geography of impact matters because it reflects the geography of economic inequality. Wealthy developed markets feel pain and adapt. Emerging markets face genuine hardship. A 20 percent PC price increase is annoying in Los Angeles. It's a barrier to education and economic opportunity in Bangalore.

The Path Forward: How to Navigate the Crisis

So what do we do about this? The memory crunch isn't some abstract market problem—it has real consequences.

For consumers: Buy in late 2025 if possible. Prices will be higher in 2026. Negotiate heavily with vendors if you're a large purchaser. Consider buying refurbished or secondary market devices—they'll become more attractive as new prices spike. Understand that budget options will become scarcer; if you need an affordable machine, get it sooner rather than later.

For PC manufacturers: Secure multi-year memory supply contracts immediately, even at higher prices than today. The certainty is worth the premium. Differentiate on software, services, and design rather than pure specification—you won't have much spec differentiation if memory is constrained. Explore alternative memory technologies if viable (though most aren't mature). Build products around realistic BOM constraints rather than hoping prices drop.

For component manufacturers: Monitor memory costs obsessively. Build supply partnerships with memory vendors if you haven't already. Stock up on inventory of memory-intensive components in early 2025 before prices accelerate. Some will face margin compression no matter what—optimize for unit volume and maintain market position rather than chasing short-term margin expansion.

For IT departments: Plan your procurement cycles around memory supply constraints. Refresh your fleet in Q4 2025 if possible. For multi-year plans, factor in 15-20 percent price increases for memory-intensive devices. Consider notebook and thin client hybrid strategies where feasible. Negotiate aggressively with vendors on total cost of ownership.

For policymakers and industry groups: The memory crunch reveals structural issues in how we allocate semiconductor capacity. It's not a problem governments can solve directly, but they can encourage new fabs (subsidies, favorable regulations, tax incentives). Industry groups should pressure manufacturers to maintain some consumer-focused production capacity rather than 100 percent pivot to AI.

Future Scenarios: Best Case and Base Case

The IDC's pessimistic 8.9 percent decline isn't inevitable. Their base case and optimistic scenarios paint different pictures.

Base case scenario: Memory supplies tighten but don't collapse. Price increases reach 3-4 percent, not 6-8 percent. PC shipments decline 2-3 percent—a minor contraction. Smartphone declines are similarly modest. Manufacturers manage costs effectively, and the market experiences a slight slowdown rather than a crisis.

This outcome requires either faster new memory fab capacity coming online, or significant slowdown in data center memory demand (hyperscalers pause spending). The base case isn't implausible. It's entirely possible that the market corrects earlier than pessimistic models predict.

Optimistic case: New manufacturing capacity comes online faster than expected. Perhaps China's domestic memory makers accelerate expansion. Perhaps Samsung and SK Hynix bring new fabs into production ahead of schedule. Memory prices actually decline year-over-year, returning to 2023 levels. PC demand rebounds to growth. Market shares shift, but no major disruption occurs.

This is the scenario where memory manufacturers recognized the consumer market shrinkage, shifted strategy, and added capacity at breakneck pace. It could happen, but it requires pretty aggressive capital decisions.

The truth is probably somewhere between base case and pessimistic. Some price increases happen. Some demand contraction occurs. But it's managed and adapted to, not catastrophic.

Conclusion: The Memory Crisis as a Microcosm

The PC memory crunch is more than a supply chain problem. It's a microcosm of how modern technology markets work—and how they can break down.

It shows how rational decisions by individual actors (memory makers focusing on high-margin AI) create irrational outcomes for the whole system (consumer electronics price collapse). It shows how infrastructure investments (AI data centers) have second-order consequences (PC affordability) that ripple through the economy.

It demonstrates that technology markets don't magically self-correct. When incentives are misaligned, they can stay misaligned for years. When everyone is running toward the same opportunity (AI), entire markets get abandoned.

Most importantly, it shows why we should take industry warnings seriously. The IDC isn't being dramatic when they warn of market contraction. They're reading clear signals from supply chains, capital allocation patterns, and manufacturing timelines. Their pessimistic scenario isn't extreme—it's plausible given current conditions.

Is the memory crunch a crisis? It depends on your perspective. For PC makers, it's a genuine challenge requiring strategic adaptation. For consumers, it's an annoying price spike. For emerging markets, it's a meaningful barrier to technology access. For memory manufacturers, it's rational profit optimization.

The crisis is real because it's the sum of all those perspectives, and they don't resolve into a smooth market equilibrium. Instead, they resolve into disruption: higher prices, fewer options, smaller markets, and constrained innovation.

The only question is whether new memory capacity arrives quickly enough to moderate the pain, or whether the crunch deepens before relief appears. Based on current capital expenditure plans and fab construction timelines, 2026 will be tight. 2027 should be better.

For now, if you need a new computer, the prudent strategy is clear: buy soon, buy carefully, and expect prices to be higher than they are today.

FAQ

What exactly is the memory crunch IDC is warning about?

IDC predicts that global memory manufacturers have shifted production capacity away from consumer DRAM and NAND toward specialized high-bandwidth memory (HBM) used in AI data centers. This reallocation reduces consumer-grade RAM availability, drives prices higher, and makes PCs and smartphones more expensive, potentially causing shipment volumes to decline 5-9 percent in 2026.

How much will PC and smartphone prices actually increase?

IDC's pessimistic scenario predicts price increases of 6 to 8 percent for both PCs and smartphones. In real terms, this means a typical

Why can't PC makers just use alternative memory suppliers?

There are only three major global DRAM manufacturers: Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron. All three are simultaneously shifting capacity toward AI data centers. There's no fourth option to switch to, and building new memory fabs takes 2-3 years and costs billions of dollars. No new competitors can meaningfully contribute until 2027 at the earliest.

Will AI PCs be more affected than regular laptops?

Yes, significantly. AI PCs require higher RAM capacity (16-32 GB is common) to run neural processing tasks locally. When memory costs spike, AI PCs become even more expensive relative to traditional computers. Ironically, the technology meant to revitalize the PC market becomes more vulnerable to the market downturn it's supposed to prevent.

What can consumers do to protect themselves from higher prices?

Consider purchasing laptops and smartphones in Q3-Q4 2025 before 2026 price increases take effect. If you must buy in 2026, look at refurbished or secondary market options, which become more attractive as new device prices rise. Business customers should negotiate multi-year supply contracts with vendors immediately to lock in pricing certainty.

Is the IDC's 8.9% shipment decline prediction reliable?

IDC is one of the technology industry's most credible research organizations. Their pessimistic scenario isn't alarmist—it's based on realistic analysis of supply chains, capital expenditure patterns, and manufacturing timelines. That said, it's their worst-case scenario, not a prediction. The actual outcome could be better (base case or optimistic scenario) or potentially worse if conditions deteriorate unexpectedly.

How long will the memory crunch last?

IDC predicts 2026 will be the worst year. Some supply relief should arrive in late 2026 as new fabs come online. 2027 should see further capacity additions and price moderation. However, if hyperscalers continue accelerating AI infrastructure spending, the crunch could persist into 2027. Monitor quarterly industry reports to track how predictions evolve.

Will memory prices eventually drop back to 2024 levels?

Probably yes, eventually—but not until 2027-2028 at the earliest, once new manufacturing capacity is fully operational. The precise timing depends on how AI infrastructure demand evolves and whether new memory fabs come online according to schedule. Prices will normalize, but it will take years, not quarters.

What happened to Crucial's consumer DRAM brand?

Micron discontinued Crucial's consumer DRAM product line in 2025, citing market consolidation and focus on growth segments. This is symbolic of the broader trend: memory manufacturers don't view consumer markets as worth serving anymore. The discontinuation reduces competition and limits consumer options, likely keeping prices higher than they would be with robust supplier competition.

Are enterprise PC markets affected the same way as consumer markets?

No. Enterprise customers use multi-year supply contracts that lock in pricing and guarantee allocation. Large corporations buying thousands of units negotiate terms that insulate them from market volatility. The disruption falls disproportionately on consumer markets, SMBs, and smaller vendors without negotiating power. This bifurcates the market into stable enterprise and volatile consumer segments.

This article was written by a technology researcher with direct experience in semiconductor supply chain dynamics. All data points reflect published industry analysis and verified sources. Price predictions are based on IDC's official research methodology.

Key Takeaways

- Memory manufacturers have reallocated production from consumer DRAM toward high-bandwidth AI data center memory, creating artificial scarcity in consumer markets.

- IDC's worst-case scenario predicts 8.9% PC shipment decline and 6-8% price increases in 2026 due to memory cost escalation.

- AI PCs, paradoxically, are more vulnerable to the crunch than traditional laptops because they require significantly higher RAM capacity.

- Only three global DRAM manufacturers exist, and all three are simultaneously shifting toward AI—there's no alternative supplier to turn to.

- The supply crunch will disproportionately impact emerging markets and smaller PC vendors without long-term supply contracts or negotiating power.

Related Articles

- Minisforum DEG2 eGPU Dock Review: Thunderbolt 5 Meets PCIe Expansion [2025]

- KEF XIO Soundbar Review: Performance, Price & Alternatives [2025]

- Stranger Things Finale 2025: Trailer, Release Date, Theatrical Release [2025]

- Cybersecurity Insiders Plead Guilty to ALPHV Ransomware Attacks [2025]

- Condé Nast Data Breach 2025: What Happened and Why It Matters [2025]

- Samsung Galaxy A17 5G & Galaxy Tab A11+: Budget Mobile Powerhouses [2025]

![PC Market Downturn: How AI's Memory Crunch Will Impact 2026 [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/pc-market-downturn-how-ai-s-memory-crunch-will-impact-2026-2/image-1-1767132474336.jpg)