Nuclear Power vs Coal: The AI Energy Crisis [2025]

Back in 2017, nobody was talking about artificial intelligence needing massive amounts of power. The Trump administration was busy trying to prop up coal and nuclear plants with subsidies while renewables ate their lunch. It didn't work. Coal kept declining, nuclear kept struggling, and the market basically said: thanks, but no thanks.

Fast forward to 2025, and suddenly everything's different.

AI is the new energy villain. Or maybe the new energy savior, depending on who you ask. Companies like Google, Amazon, and Microsoft are scrambling to find power sources to run their data centers. The federal government is now actively pushing nuclear energy as the solution. Coal plants that were scheduled to shut down are getting extended lifelines. And the entire US power grid is being caught in the middle of a fundamental question: can the infrastructure that's been built over decades actually support what's coming next?

The irony is thick. The same energy sources that failed to get meaningful support five years ago are now being repackaged as essential to America's AI future. But this time, the underlying economics and timelines are just as questionable as they were before.

TL; DR

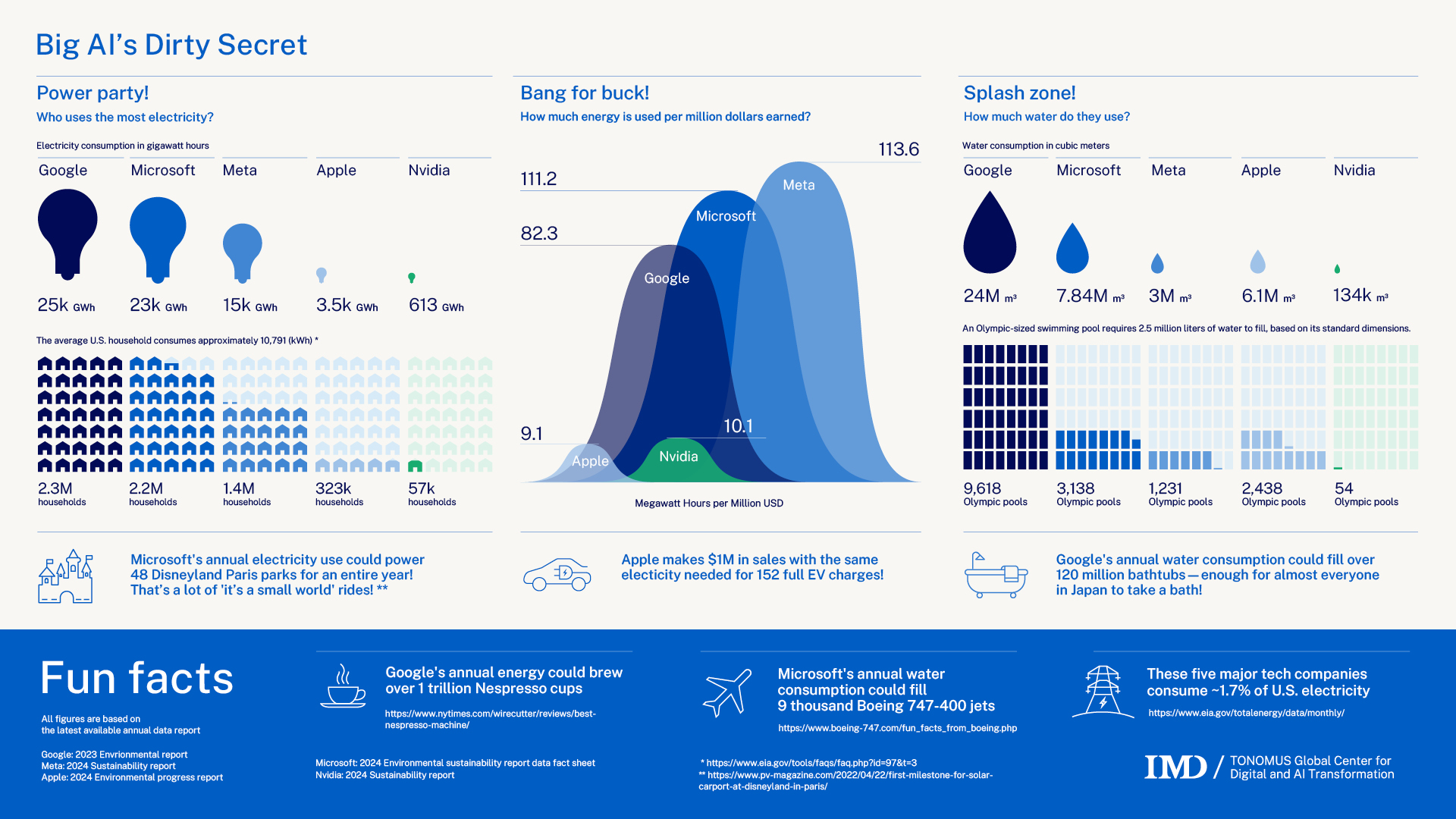

- AI data centers demand insane amounts of power: Some facilities use as much electricity as small cities, forcing grid operators to think creatively about power sources

- Nuclear is getting a genuine second chance: Public support is at 15-year highs, and tech companies are actually betting billions on reactor restarts and new construction

- Coal's revival is temporary at best: Despite emergency federal orders keeping plants online, utilities are still systematically replacing coal with nuclear and renewables long-term

- The timelines don't match reality: Tech companies promise operational reactors in 2-3 years, but nuclear construction historically takes 10+ years, even with aggressive federal support

- Data center siting is becoming the new NIMBY battlefield: Communities are pushing back hard on massive power plants being built nearby, concerned about grid stability and water usage

Estimated data shows that while large nuclear reactors have a high upfront cost per megawatt, solar plus battery storage offers a competitive alternative with potentially lower costs over a 20-year horizon.

The AI Energy Bomb Nobody Saw Coming

Let's be honest about what's happening: AI companies built massive models that nobody really understood the power requirements for. Then they kept building bigger models. And bigger ones. And bigger.

Now they're discovering that running a large language model inference operation is more power-hungry than operating a small nation's worth of infrastructure.

A single large data center running AI models can consume between 100 and 500 megawatts of power on a continuous basis. For context, that's roughly equivalent to what 80,000 to 400,000 homes use. Some facilities are even larger. We're talking about power consumption that rivals small industrial cities.

The problem is that most of the power grid was built assuming data centers would use maybe 10-50 megawatts. Nobody was planning for distributed AI inference operations that needed 10 times that amount, available 24/7, with minimal downtime tolerance.

This created an immediate crisis for tech companies. They can't just plug into the existing grid and hope for the best. Grid operators in places like Virginia, Texas, and California started telling them: sorry, we don't have spare capacity for you. Come back in 5-10 years when we've built new infrastructure.

So the tech companies did what tech companies do: they started looking for alternative solutions. And they kept coming back to one option that nobody had seriously considered in years: nuclear energy.

Why Nuclear Suddenly Became Sexy Again

Nuclear energy hasn't been fashionable in the United States for decades. After Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, Fukushima, and countless regulatory headaches, the industry became radioactive in a different way: politically toxic.

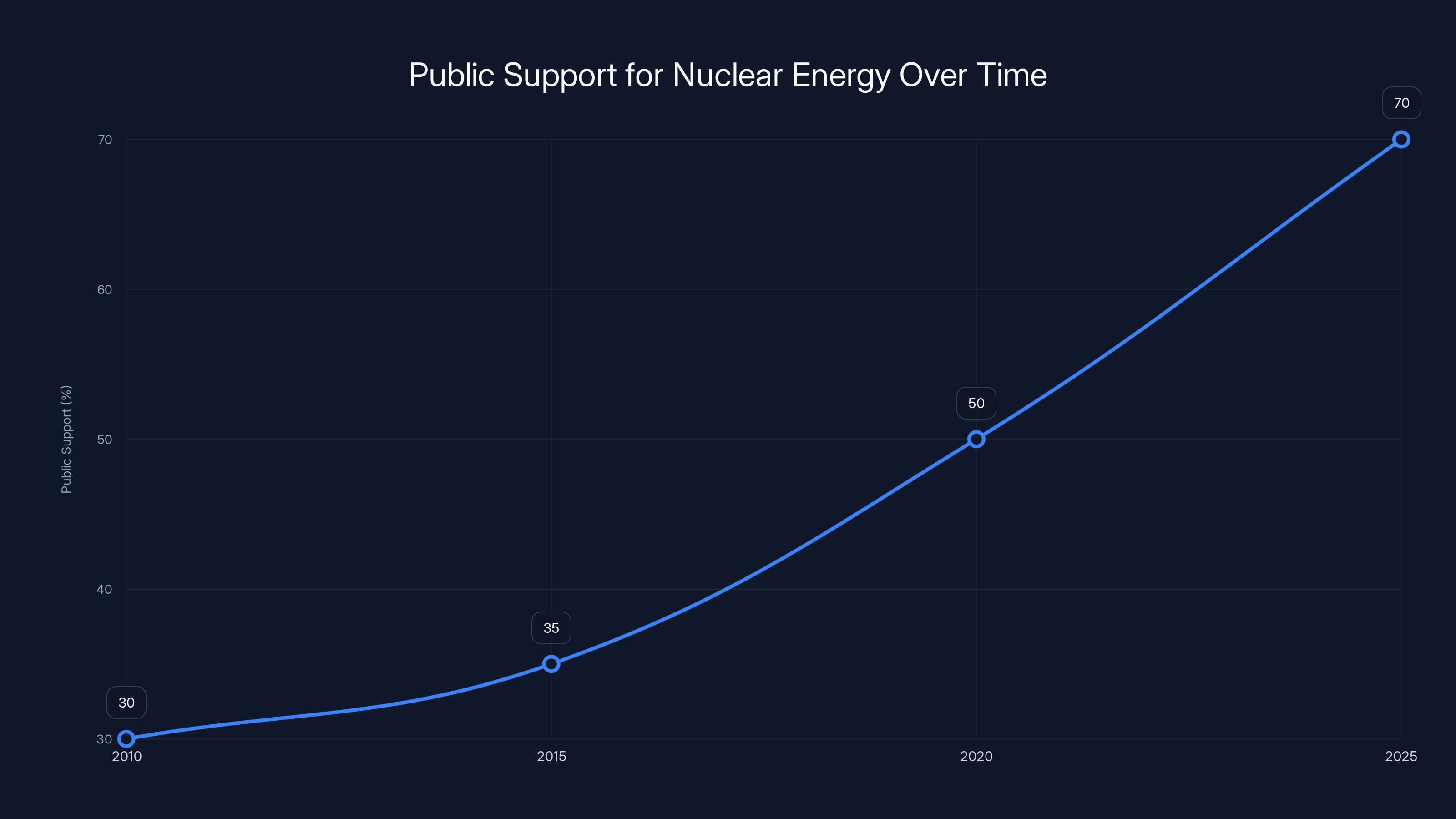

But something shifted. Public support for nuclear power started climbing in the late 2010s, partly because climate concerns made people realize that coal and gas were actively killing the planet. Nuclear doesn't produce carbon emissions. It's clean. It's stable. It produces power 24/7, unlike solar and wind.

Then AI happened, and suddenly nuclear became strategically important. Tech companies needed massive amounts of reliable baseload power. They couldn't get it from solar farms, which only work when the sun's up. Wind farms are intermittent. Hydroelectric is geographically limited. Gas plants are expensive to run and contribute to climate change, which contradicts the companies' sustainability messaging.

Nuclear became the only answer that made sense: high power output, no direct carbon emissions, scalable, and proven technology.

The federal government noticed this alignment and moved aggressively. In May 2025, President Trump signed a series of executive orders aimed at accelerating nuclear energy deployment, including directives to construct 10 new large reactors by 2030. A pilot program at the Department of Energy started generating actual breakthroughs from smaller startup companies.

Chris Wright, the Energy Secretary, explicitly framed nuclear as the solution to AI's power needs. The administration began restructuring the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to streamline approvals. Federal loan guarantees were offered. Suddenly, the entire weight of government policy shifted toward nuclear energy.

And here's the kicker: it worked. Microsoft signed a deal to restart Three Mile Island, the most infamous nuclear site in American history, with a $1 billion federal loan backing the project. Google signed multiple deals with nuclear companies. Amazon partnered with small modular reactor developers. The private sector and federal government were aligned in a way that hadn't happened in decades.

Public support for nuclear energy has significantly increased from 30% in 2010 to an estimated 70% in 2025, driven by climate concerns and strategic energy needs. (Estimated data)

The Math Behind Nuclear's Revival: Capacity vs Reality

On paper, the nuclear expansion makes sense. The math works like this:

Large AI data centers need approximately 300 to 500 megawatts of continuous power. A typical large nuclear reactor produces around 1,000 megawatts. So theoretically, you could power 2-3 major data centers with a single reactor.

The problem is the timeline equation:

That equals roughly 10-15 years in the best case scenario, assuming nothing goes wrong.

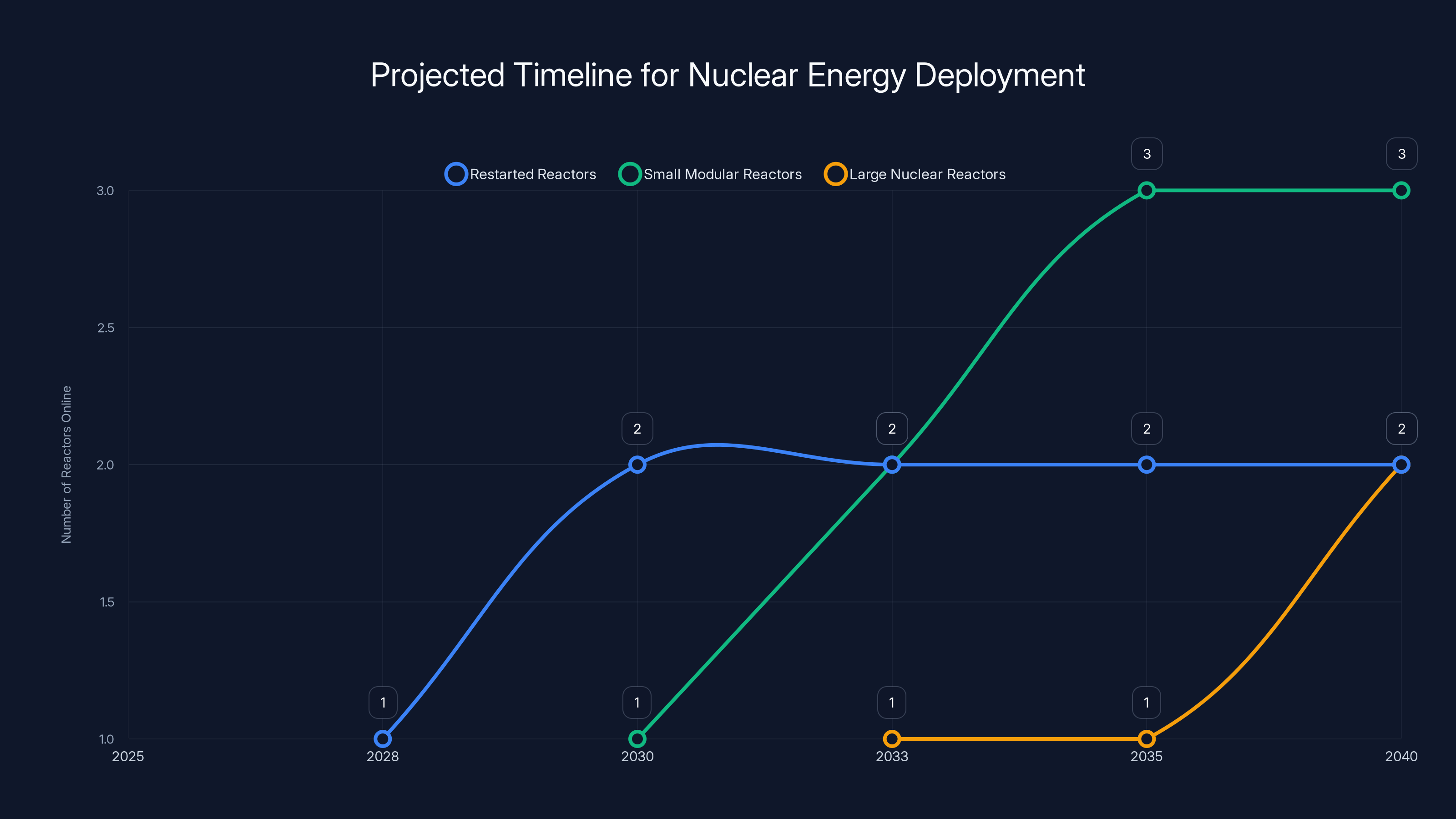

Meanwhile, tech companies are saying they need power now. Microsoft's Three Mile Island restart is projected to be online by 2028 or 2029, though that timeline has already slipped multiple times. Google's nuclear deals promise delivery by 2030. But these are the optimistic projections, stated in press releases and investor presentations.

Historically? Nuclear plants take longer. Much longer. The current construction delay of 10+ years isn't unusual; it's the norm. The Vogtle expansion in Georgia was supposed to be finished years ago. The project ballooned from an estimated

Small modular reactors, which several startups are developing with federal backing, theoretically offer a faster path. These are smaller, factory-built reactors that could theoretically be deployed faster than traditional large reactors. But the technology is still largely unproven at commercial scale. No small modular reactor is currently operating in the United States.

So we have a situation where the demand is immediate, the political will is newfound, the financing is available, but the physics and engineering of building nuclear infrastructure remain obstinate. You can't accelerate nuclear construction the way you can accelerate hiring engineers or renting office space.

Coal Gets an Unexpected Second Wind

While nuclear is getting the prestige and the federal funding, coal is getting something different: emergency extensions.

Earth's irony reaches peak levels here. Coal plants that utilities had already retired or scheduled for retirement are being forced to stay online via emergency federal orders. Energy Secretary Chris Wright issued mandates keeping specific coal plants operational. The administration also began aggressively rolling back pollution regulations to make coal plants cheaper to operate.

Why? Because the grid needed immediate power, and coal plants were already built, already connected, already capable of operating.

Over two dozen coal generating units that were originally scheduled to retire have now been given extended lifespans. Some are getting 3-5 year reprieves. A few are potentially staying online indefinitely. It's a temporary stay of execution for an industry that's been in long-term decline.

The economics tell the real story, though. Yes, federal orders are keeping some coal plants online. But the largest utilities in America—the ones that actually operate most of the grid—are simultaneously announcing aggressive retirements from coal and investments in nuclear and renewables.

A major analysis of US power sector trends shows that almost all of the 10 largest utilities are significantly reducing their coal reliance while increasing nuclear capacity. These utilities aren't following federal mandates; they're following market signals and shareholder pressure. Coal, they've decided, is a sunset industry.

This creates a weird bifurcated energy landscape. In some regions with federal political leverage, coal plants stay online. In regions following market logic, coal is being systematically replaced with nuclear and renewables. The long-term direction is clear: coal is done. The federal emergency orders are just slowing the inevitable transition.

The Data Center Siting Crisis: NIMBY on Steroids

Here's something nobody's talking about enough: even if we solve the power supply problem, we still have to deal with the data center siting problem.

Communities don't want massive data centers in their backyard. They're loud. They're water-intensive (data centers need enormous amounts of water for cooling). They transform the landscape. And they don't generate many jobs relative to their physical footprint.

So even as tech companies are eagerly signing nuclear deals, they're running into fierce local opposition. Towns and counties are passing ordinances restricting data center development. Virginia, which hosts some of the largest data centers in the world, is facing increasing community pushback. Iowa, another major data center hub, is seeing similar resistance.

This creates a compounding problem. Tech companies need power and location. The power has geographic limitations (you can't easily move a nuclear reactor to wherever the cheapest land is). The location has political limitations (you can't force communities to accept massive infrastructure projects). These constraints don't align neatly.

Some companies are trying to work around this by using retired industrial sites or partnering with existing power plants in places where opposition is lower. But there's only so much available real estate at locations with spare power capacity.

This siting crisis might actually be the bottleneck that determines how quickly AI infrastructure scales. It's not necessarily the power generation that limits growth; it's where that power gets connected to the network and where people are willing to tolerate the physical plants.

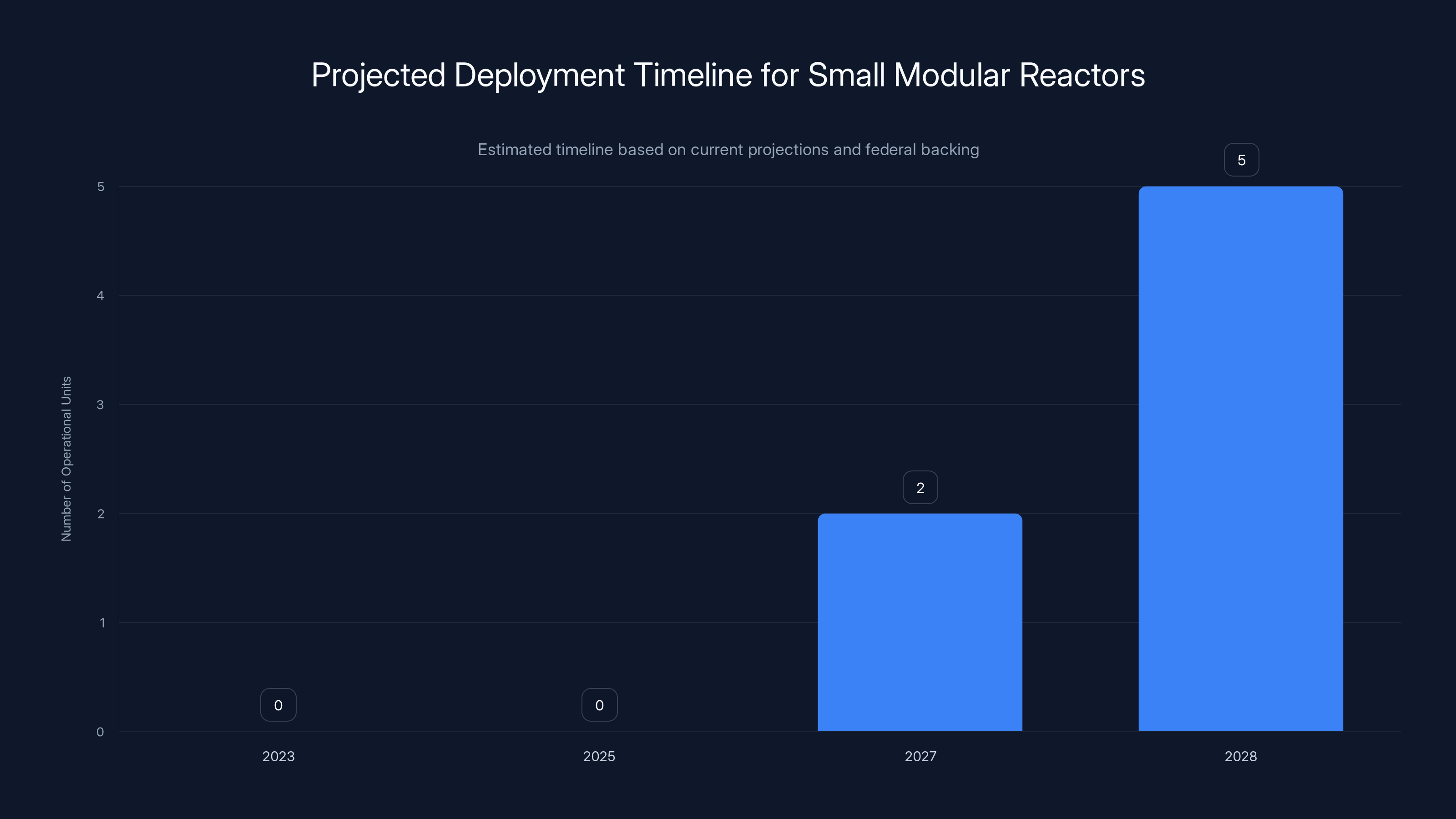

Estimated data shows that restarted reactors may come online by 2028, while small modular reactors could be operational by 2030-2035. Large reactors are projected to be online by 2033-2040.

Small Modular Reactors: Promise and Peril

Multiple startups are developing small modular reactors, and the federal government is betting big on this technology as the solution to the capacity and timeline problems.

The theory is attractive: factory-built reactors that are smaller (typically 100-300 megawatts each), more flexible in deployment, and faster to construct than traditional massive reactors. They could theoretically be deployed at multiple locations rather than requiring one giant plant per region.

Several companies have received federal backing and loan guarantees. Some are talking about having operational units by 2027 or 2028. The technology is real, in the sense that it's been tested at small scales and in specific applications like naval vessels.

But there's a significant caveat: no commercial small modular reactor is currently operating at scale in the United States. The technology is proven in concept but unproven at the commercial level. This creates a financing and regulatory risk.

Investors are rightfully skeptical. Some valuations being placed on small modular reactor companies seem divorced from reality, especially when those companies have deep connections to the Trump administration. An $80 billion federal deal with Westinghouse, one of the largest nuclear companies, was announced in October but was "light on details," raising more questions than answers about what the government was actually committing to and what Westinghouse was actually promising.

There's also a critical issue that gets underexplored: even if small modular reactors work technically, they might not be cheaper than alternatives. Nuclear power's cost comes primarily from construction, regulatory compliance, and financing, not from operational complexity. Building multiple small reactors might actually be more expensive than building one large reactor, because you lose economies of scale.

So while small modular reactors are getting federal love, they remain a high-risk, high-reward play. They could be revolutionary. They could also be an expensive bet on unproven technology.

Renewables Keep Winning on Price

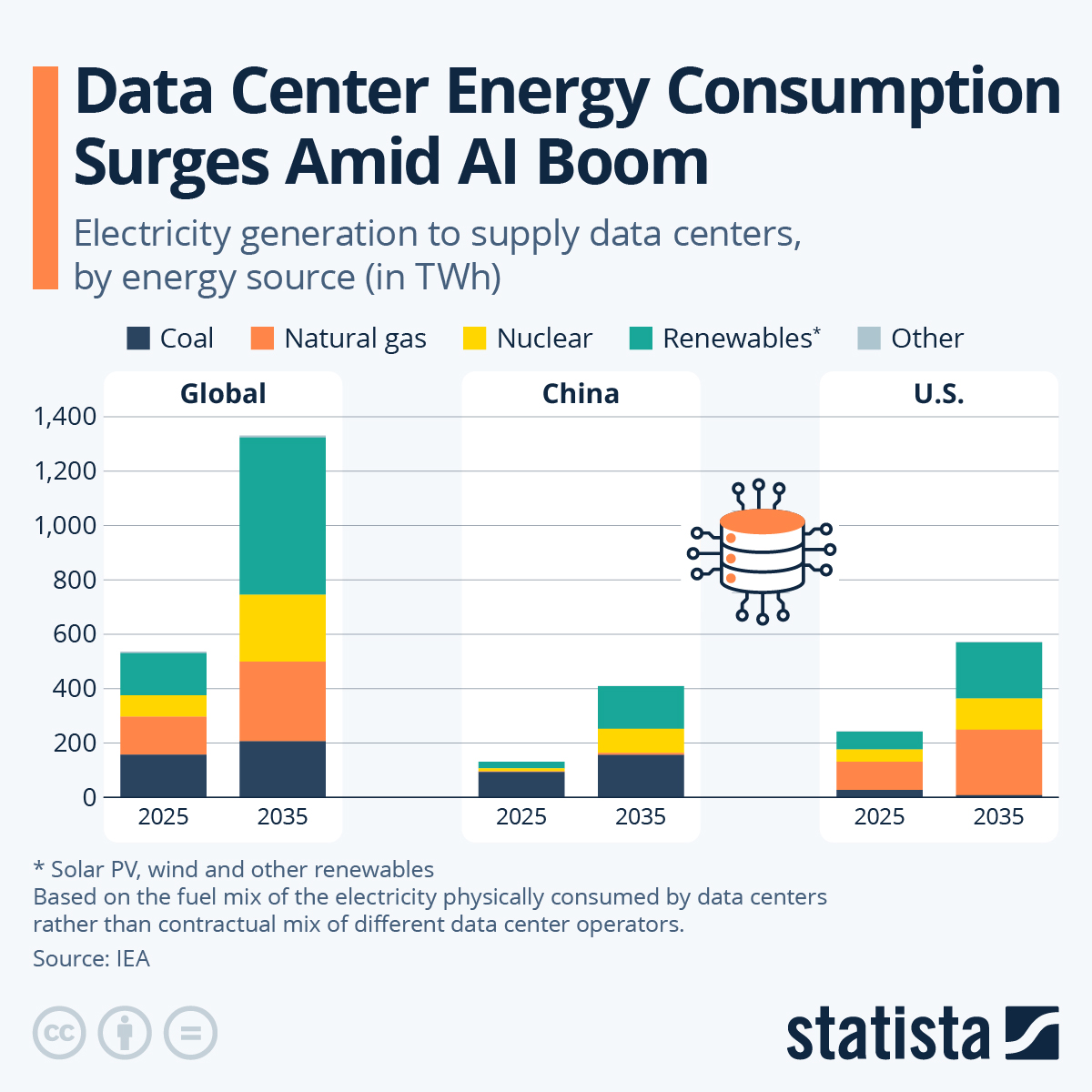

While everyone's debating nuclear vs. coal vs. natural gas, renewables are quietly dominating economically.

Utility-scale solar and onshore wind are now the cheapest forms of energy available in most US markets, even without government subsidies. They're cheaper than natural gas in many regions. They're dramatically cheaper than coal. And they don't require the multi-year construction timelines or regulatory complexity of nuclear.

This is a fundamental problem for the nuclear expansion narrative. If you're trying to solve grid capacity problems, renewables plus battery storage (which is getting cheaper rapidly) might actually be a better solution than nuclear, purely from an economic and timeline perspective.

A utility could theoretically deploy 1,000 megawatts of solar capacity faster than it could construct a single large nuclear reactor. The cost would probably be lower, even accounting for battery storage infrastructure.

The federal government and tech companies are promoting nuclear for understandable reasons: nuclear provides reliable baseload power, it's politically attractive as a climate solution, and it aligns with national security thinking about energy independence. But none of these reasons change the fundamental economics.

So we're likely to see a weird energy landscape over the next decade. New nuclear capacity will be built, probably slower than promised but faster than the historical average, driven by aggressive federal support and tech company demand. But the actual energy growth will probably come largely from renewables, which continue getting cheaper and faster to deploy.

The grid of 2035 might have new nuclear plants running alongside massive solar farms and wind installations, all connected through better storage and grid management systems. It won't be the nuclear-dominated vision some people are imagining, but it probably won't be purely renewable either.

The Grid Integration Problem: No One's Really Talking About This

Here's a problem that gets almost no attention in the policy discussions: how do you actually integrate hundreds of gigawatts of new AI-powered data centers into a grid that wasn't designed for them?

The US electrical grid is more like a fragile ecosystem than a simple infrastructure system. It operates on the principle of balance: generation has to match demand second by second. Too much supply and voltages spike. Too little and frequencies drop. The grid has built-in buffers and spinning reserves to handle fluctuations, but those buffers are getting tighter as demand increases.

Data centers are different from traditional loads. They're massive (300-500 megawatts for a single facility), they operate 24/7 with minimal variation, and they're geographically concentrated. When a data center suddenly needs to cool down from 500 megawatts to 450 megawatts (which happens constantly as workloads fluctuate), that's a 50-megawatt demand reduction happening in seconds. The grid has to adjust instantly.

Multiply that by dozens of data centers across a region, and you've got hundreds of megawatts of demand fluctuation happening constantly. Traditional power plants can throttle up and down, but they're not infinitely flexible. The grid operator has to coordinate between the data centers, the power plants, and the renewable sources to keep everything balanced.

This is solvable—grid operators have smart systems to handle it—but it requires real-time coordination and investment in transmission infrastructure. It's not something you can just bolt onto the existing system and hope it works.

Few policy discussions actually address this infrastructure investment requirement. Everyone's focused on "building X reactors" without really discussing how those reactors connect into the grid, how the transmission infrastructure needs to change, and what the system-wide impacts are.

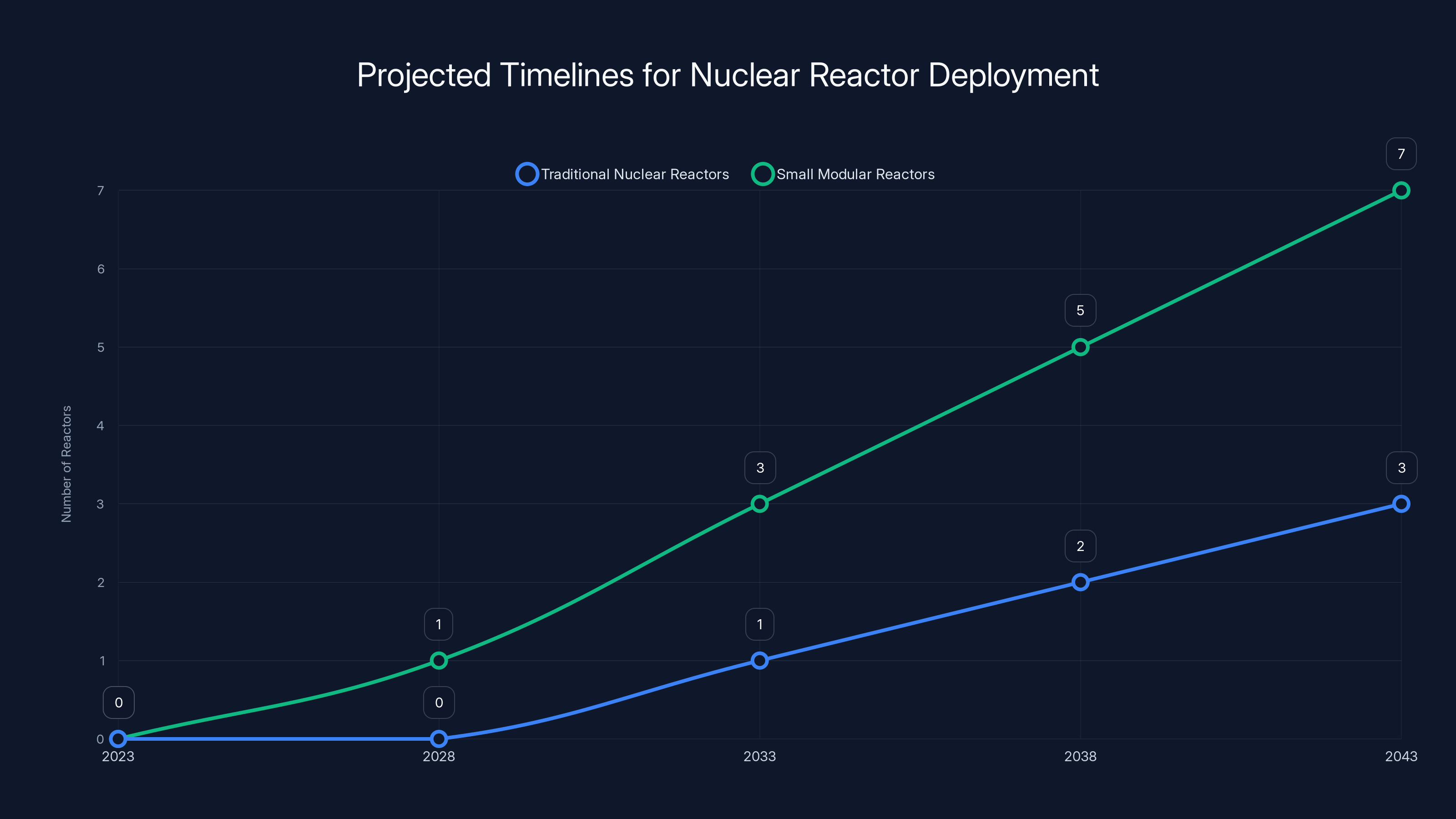

Traditional nuclear reactors have longer deployment timelines, with significant delays, while small modular reactors are projected to be deployed more rapidly, though still unproven at scale. Estimated data.

Water Usage: The Hidden Cost Nobody's Calculating

Nuclear plants and data centers both need enormous amounts of water. Nuclear for cooling the reactor core and condensing steam. Data centers for cooling servers and supporting infrastructure.

We're talking about millions of gallons per day, potentially in regions where water is already constrained.

This is especially problematic in the Southwest and parts of the Midwest, where water availability is already under stress from drought conditions, agricultural demand, and climate change. Dropping a massive nuclear plant or data center in these regions doesn't just add power consumption; it adds competing water demands in places where water is genuinely scarce.

Utilities are trying to address this through recycling and alternative cooling methods, but the fundamental constraint remains. You can't generate power without using water, and you can't cool data centers without water.

This could become a serious bottleneck for expansion, especially in water-constrained regions. It's a problem that doesn't get adequate attention in policy discussions because it's not as visible as power generation capacity, but it could be just as limiting.

The Economics of Nuclear Construction: Why It Costs So Much

People often assume nuclear plants are expensive because of regulation. That's a convenient narrative, and it's partially true, but it misses the deeper economic reality.

Nuclear plants are expensive because nuclear plants are expensive. They're incredibly complex engineering projects. The reactor itself is only a fraction of the total cost. The containment structure, the cooling systems, the backup systems, the security infrastructure, the training of personnel—all of this adds up.

A single large nuclear reactor typically costs

There's no way around this cost structure without fundamentally changing how nuclear plants are built. And that's hard. Once you start cutting corners on nuclear safety or quality control, you're playing with fire—literally and figuratively.

So when federal officials talk about streamlining regulations or accelerating approvals, they're not necessarily going to reduce the fundamental cost of construction. They might speed up the timeline by a year or two, but they're not going to cut costs in half.

This is why some alternative energy sources might actually make more economic sense. Solar plus battery storage might be more expensive upfront in some regions, but the cost per megawatt is lower, and you can deploy it faster. Over a 20-year planning horizon, that might actually be the better economic decision.

The Political Economy: Why This Matters Beyond Energy Policy

The nuclear revival isn't just an energy policy story. It's a story about political economy, industrial policy, and how government decisions shape investment flows.

The Trump administration has explicitly positioned nuclear as a national priority. This means federal loans are available for nuclear projects but not for comparable renewable projects. Regulations are being streamlined for nuclear but not for solar or wind. Federal money is flowing toward nuclear infrastructure.

This creates a tilted playing field. Tech companies, seeing federal support, are incentivized to invest in nuclear partnerships. Utilities, seeing government backing, are more willing to finance nuclear projects. Meanwhile, renewables, which might actually be the better economic choice in many cases, are getting less attention and less federal support.

Investors with ties to the Trump administration are positioning themselves for nuclear projects. Some of the valuations being placed on small modular reactor startups suggest there's more political speculation than fundamental economic analysis happening.

This doesn't mean nuclear will fail. It means that the nuclear expansion is being driven partly by market logic (tech companies need power, nuclear is available) and partly by political logic (nuclear is being positioned as strategically important).

The outcome will probably be a mixed portfolio. Some nuclear plants will be built or restarted. But the actual energy growth will come largely from renewables, because economics ultimately matter. Tech companies might have federal support for nuclear, but their investors care about costs. If renewables end up being cheaper, companies will gravitate toward them regardless of government preferences.

That said, government support does matter. It can accelerate timelines, reduce financing costs, and support industries that wouldn't survive on purely economic grounds. So the federal push for nuclear might successfully create a nuclear-powered future, even if it's not the most economically optimal choice.

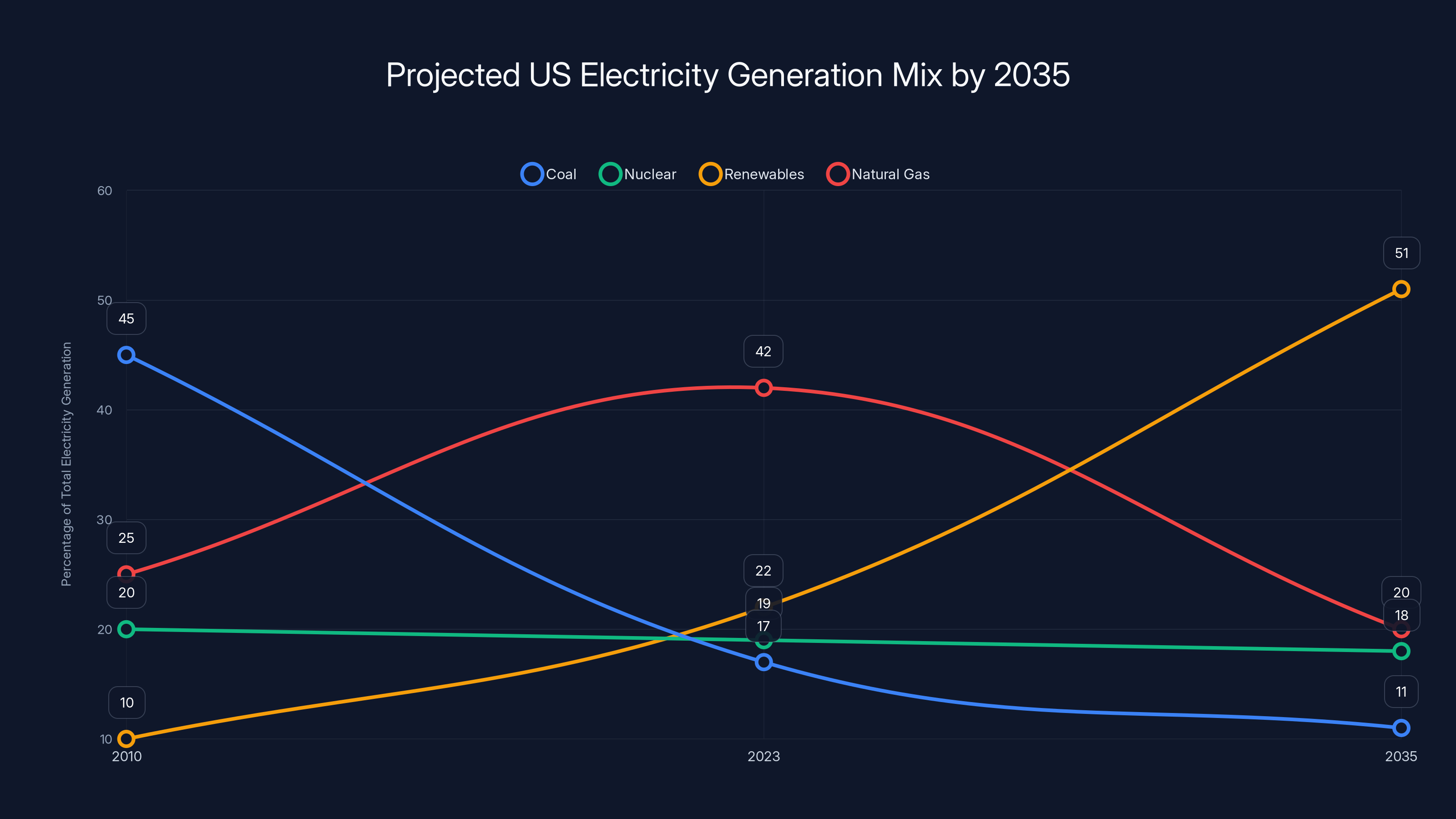

Renewables are projected to surpass 50% of US electricity generation by 2035, while coal's share will decline significantly. Estimated data based on current trends.

Data Center Efficiency: The Wildcard Nobody's Considering

Here's something that could completely change the energy equation: what if AI models become more efficient?

Right now, we're in a phase where bigger is better. Larger models perform better. But there's increasing research into making models more efficient. Techniques like model pruning, quantization, and architectural innovation could reduce the power requirements of AI inference by 50% or more.

If that happens—if AI companies figure out how to get similar performance with half the power—then the entire energy crisis becomes half as severe. We'd need half as much new generation capacity. The nuclear expansion becomes less urgent. The grid stress becomes more manageable.

This is speculative, but it's not impossible. Every other technology has followed efficiency curves over time. As AI becomes more mature, efficiency improvements are almost inevitable.

Few policy discussions seriously consider this possibility, probably because it's uncomfortable. If efficiency improvements could solve the problem, then the urgent federal push for nuclear becomes less necessary. But this is exactly the kind of technological development that could happen.

The International Perspective: Other Countries Are Making Different Bets

While the US is pushing nuclear, other countries are making different energy choices.

Europe has invested heavily in renewables, and many European countries now get 50%+ of their electricity from wind and solar. They're building massive battery storage systems to handle intermittency. Germany's renewable penetration hit record levels recently, despite everyone saying it was impossible.

China is building nuclear plants, but it's also building renewable capacity at scales that dwarf the US. The number of solar panels China installed last year exceeded the total solar capacity of the entire United States.

This matters because it shows that different paths are possible. The US narrative "nuclear or bust" isn't the only viable approach. Other countries have made deliberate choices to go heavily renewable, and it's working.

That said, the US has its own constraints and advantages. The US has existing coal plants that can be repurposed for nuclear. The US has strong manufacturing capacity for reactor components. The US has a national security interest in energy independence. These factors push the US toward nuclear even if other countries are choosing different paths.

But it's worth keeping in mind that the US energy future isn't predetermined. Other models exist and are demonstrably working elsewhere.

Timeline Reality Check: When Will New Power Actually Come Online?

Let's do some serious timeline accounting, because the official announcements and the actual physics tell very different stories.

Restarted Coal Plants: Already online. Emergency orders kept them running, so they're providing power immediately. Timeline: already done.

Restarted Nuclear Plants: Two or three retired reactors might come back online in the next 3-5 years. The most high-profile, Three Mile Island, is targeted for 2028-2029. Timeline: 2028-2031 for the first plants, assuming no delays.

New Large Nuclear Plants: The administration ordered 10 new reactors by 2030, which is hilariously optimistic. Reality: first new large reactor probably comes online around 2033-2035, assuming everything goes well. Timeline: 2033-2040.

Small Modular Reactors: First commercial units target 2027-2029, but this is extremely optimistic. More realistic timeline: 2030-2035 for first commercial deployment at scale.

New Renewable Capacity: Can be deployed in 2-3 years. Solar farms are already going online at massive scales. Timeline: continuous deployment, 100+ gigawatts possible by 2030.

So if you're doing the math: renewables can provide immediate power increases. Restarted coal provides immediate power. New large nuclear is a 10-year wait, minimum. Small modular reactors are 5-7 year wait, optimistically.

This timeline mismatch is the fundamental problem. The power is needed now. The solutions are either already available (renewables, coal) or take years to deploy (nuclear).

Estimated data suggests that small modular reactors could start becoming operational by 2027, with a gradual increase in units by 2028. Estimated data.

The Three Mile Island Restart: Everything and Nothing

Microsoft's deal to restart Three Mile Island's Unit 1 is politically and symbolically significant but economically revealing.

The reactor has been offline since 1985. Restarting it requires significant work, though it's less work than building from scratch. The $1 billion federal loan guarantee suggests the project wouldn't be economically viable without government backing, otherwise it would be financed privately.

The restart is targeted for 2028 or later, though timelines for nuclear projects have a way of expanding. Once operational, Unit 1 would produce approximately 800 megawatts of power. That's meaningful capacity, and it's power that Microsoft can contract for directly.

But here's the reality: this one reactor isn't going to solve the AI power crisis. It helps, but it doesn't scale to what's actually needed. If every major tech company that needed power got one restarted reactor, you might have 5-10 operational plants by 2030. That's maybe 8,000 megawatts of power. The total new demand from AI might be 100,000 megawatts or more by 2030.

So the Three Mile Island restart is both a sign that nuclear is back in play and a reminder of how limited the near-term capacity actually is. It's a genuine step forward, but it's not a solution to the problem.

Grid Reliability: The Overlooked Risk

In all the discussion about generation capacity, less attention goes to an equally important question: will the grid actually remain reliable as all this new load comes online?

The grid operates with built-in redundancy and reserve capacity. When you add massive data center loads, you're reducing the margin of safety. Grid operators have to reserve capacity to handle sudden generator failures or demand spikes. If you're operating at 95% capacity instead of 85% capacity, you have much less room for error.

This is why grid operators in places like Virginia and California are saying "no" to new data center connections. They don't have the spare capacity, and they're concerned about reliability.

Building new generation capacity doesn't automatically solve this because generation capacity isn't the only constraint. You also need transmission capacity, distribution equipment, and operational reserve. All of that has to be sized to handle the new loads.

This is where the grid integration problem becomes critical. You can't just build a nuclear plant in a remote location and call it solved. You have to connect it to the grid with transmission lines, you have to manage the load flow, and you have to ensure the whole system remains stable.

Utilities are working on this, but it requires coordination, planning, and investment. It's less glamorous than announcing a new reactor, but it's equally important.

The Role of Battery Storage: The Accelerant Nobody's Fully Appreciated

Battery storage technology is improving rapidly and becoming cheaper just as quickly. This changes the entire calculus around renewables versus nuclear.

With cheap battery storage, renewables become dispatchable. You can store excess solar generation during the day and deploy it at night. You can store excess wind generation when the grid is full and deploy it when demand spikes.

This means renewables can actually function as baseload, which was their previous disadvantage. Yes, the batteries add cost, but batteries are getting exponentially cheaper while renewable generation costs remain relatively stable.

For tech companies evaluating power sources, batteries plus renewables might actually be more attractive than nuclear when you account for deployment speed and financing terms.

Battery technology could quietly be the most important development in the energy landscape, even though it gets less attention than nuclear or renewables.

Venture Capital and Energy Policy: Follow the Money

A lot of what's happening in nuclear energy right now is driven by venture capital and private equity looking for the next big opportunity.

Small modular reactor startups have attracted billions in funding from investors betting that this technology will be transformative. Some of these valuations are based on genuine technical optimism. Some are based on the assumption that federal support will ensure success regardless of economics.

This creates a financial incentive structure where startups might overstate their timelines or capabilities to attract investors. It's not necessarily dishonest, but it's optimistic.

When the first commercial small modular reactors come online and cost $3-4 billion each, and utilities realize they're not significantly cheaper than large reactors on a per-megawatt basis, there could be a reckoning. Some of the current valuations might prove optimistic.

That said, venture capital flowing into energy technology is generally a good sign. It means innovation is happening, and some of those bets will pay off. But it's worth remembering that not all of them will.

The Environmental Question: Are We Trading One Problem for Another?

Nuclear has no direct carbon emissions, which is great. But it does have other environmental impacts that deserve consideration.

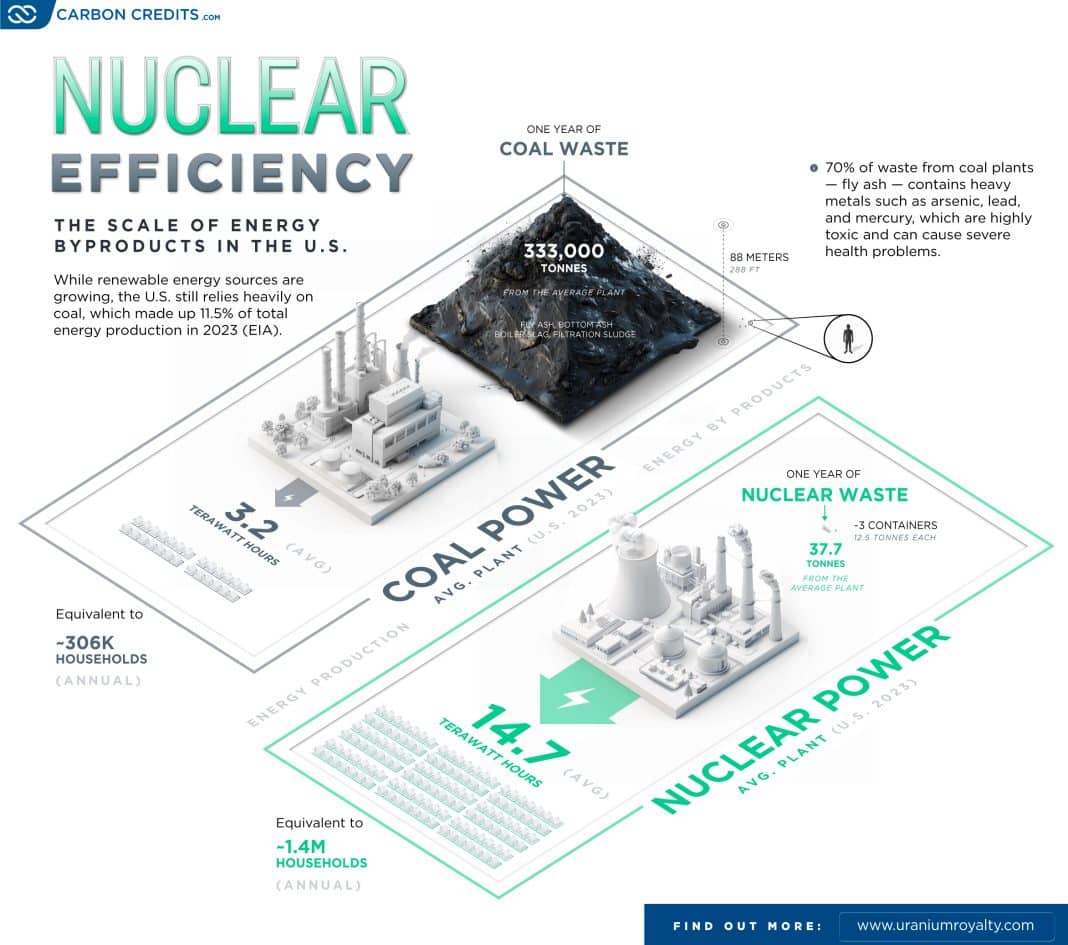

Nuclear plants produce nuclear waste, which is a long-term storage problem. No permanent disposal solution exists in the US, so waste is stored at reactor sites temporarily. This is safe, but it's not ideal long-term.

Nuclear plants also have massive water requirements for cooling, which can impact aquatic ecosystems. Water temperature changes from reactor cooling can affect fish and other organisms.

Data centers themselves are environmentally intensive. They consume enormous amounts of energy (obviously), but they also generate heat and require cooling water.

So the combination of nuclear plants and data centers creates a particular environmental profile: minimal air pollution and carbon emissions, but concentrated water usage and potential ecosystem impacts.

This doesn't make nuclear a bad choice, but it means the environmental analysis is more nuanced than "nuclear is clean." Different environmental impacts should be weighted appropriately.

Coal, by contrast, has distributed air pollution impacts (affecting millions of people), massive carbon emissions, and water pollution from mining and coal ash. From a public health perspective, coal is dramatically worse than nuclear. But coal's environmental impact is spread widely across the population, whereas nuclear's environmental impact is concentrated in specific locations. Both matter, but in different ways.

FAQ

What's driving the sudden push for nuclear energy in 2025?

AI data centers have massive power requirements—300-500 megawatts or more for large facilities. This exceeded grid capacity in many regions, prompting tech companies to seek alternative power sources. Nuclear energy, combined with federal support and public opinion shifts, became the preferred solution for providing reliable baseload power without carbon emissions.

Why are coal plants getting extended lifespans if they're being phased out?

Emergency federal orders are keeping certain coal plants online because they provide immediate power capacity while new generation sources are being built. Coal plants already exist and are already connected to the grid, so restarting them or extending their operation is faster than building new plants. However, utilities are simultaneously reducing long-term coal dependence as economics and policy favor nuclear and renewables.

How long will it actually take to bring new nuclear capacity online?

Restarted reactors might come online by 2028-2031. New large nuclear reactors typically take 10-15 years from planning to operation, so new large plants probably won't be operational before 2033-2040. Small modular reactors are promised by 2027-2029, but unproven timeline estimates suggest 2030-2035 is more realistic. This timeline mismatch is a fundamental problem because AI power demand is needed immediately.

Why don't renewables plus battery storage solve the problem faster?

Renewables can be deployed in 2-3 years and are economically competitive. Battery storage is improving rapidly. However, renewables are intermittent without storage, and building the necessary battery infrastructure takes time. Nuclear provides more immediate long-term baseload capacity, though it takes longer to build. The optimal solution is probably a combination of renewables, storage, and nuclear, deployed according to geography and timing.

What's the biggest constraint preventing data center expansion: power generation or something else?

Power generation is significant, but grid integration, transmission capacity, water availability, and local opposition to data centers are equally important constraints. Even if a region has sufficient power generation capacity, it might lack transmission infrastructure to deliver that power. Water scarcity in certain regions limits both data center and nuclear plant viability. Community opposition to data centers is intense in many areas.

How much will the federal government spend on nuclear expansion?

The

Is nuclear energy actually the best solution for AI, or is it just politically convenient?

Nuclear provides reliable baseload power without carbon emissions, making it attractive for sustainability goals. However, renewables plus storage might be more economically and logistically optimal in many cases. The federal push for nuclear is driven by strategic thinking about energy independence, climate concerns, and political ideology, not purely by economic optimization. The actual energy mix of 2030-2035 will likely be diverse, including nuclear, renewables, and some continued use of natural gas.

What happens to communities near data centers and new nuclear plants?

Local opposition to data centers is intense because of noise, water usage, and landscape transformation. Communities near nuclear plants generally accept them after initial construction, though security and safety remain concerns. The siting process for new energy infrastructure is becoming increasingly difficult, which could actually be the limiting factor for expansion rather than construction timelines or financing.

Conclusion: The Energy Future Isn't What Anyone's Planning For

Here's what's actually going to happen, based on what we know about technology, economics, and human behavior:

Nuclear will expand, but slower than promised. New large reactors will come online in the 2030s. A few restarts will happen in the next few years. Small modular reactors might work, or they might end up being an expensive experimental program. Federal support will help accelerate timelines compared to historical norms, but physics and engineering remain unaccelerated.

Coal will decline despite emergency extensions. A few plants will stay online longer than expected, but utilities are already planning replacements. By 2035, coal will provide maybe 10-12% of US electricity, down from 17% today and 45% in 2010. The trend is clear even if the timeline is uncertain.

Renewables will keep growing because they're cheap and deployable. Solar and wind will probably provide 50%+ of US electricity generation by 2035, even without accelerated federal support. Battery storage will improve dramatically, making renewables increasingly viable as baseload.

AI companies will diversify their power sources rather than betting everything on nuclear. Some will sign nuclear deals. Some will build massive solar and storage operations. Some will lobby for transmission infrastructure investment. Some will focus on model efficiency improvements to reduce power demands. It's a portfolio approach, not a single-technology bet.

The grid will become more complex, more distributed, and more managed through real-time software coordination. Grid operators will need better tools and more authority to manage demand and generation. This infrastructure modernization might be as important as any new generation source.

Data centers will continue running into local opposition in many regions. Some regions will welcome them and become data center hubs. Others will restrict them. The geography of AI infrastructure will be shaped as much by politics and community preferences as by power availability.

The federal government will continue pushing nuclear because it's strategically important and politically popular, but market forces will determine the actual energy mix. If nuclear works out economically, great. If renewables are cheaper, that's what will actually get built.

None of this means the AI energy crisis goes away. It means we adapt through a combination of new generation capacity, efficiency improvements, storage technology, grid modernization, and behavioral changes. It's not glamorous, but it's how infrastructure actually evolves.

The next decade will determine whether nuclear energy actually makes a comeback or whether this moment of political support creates limited capacity gains. Either way, the energy system is changing fundamentally, and nobody fully understands what the 2035 grid will look like. That uncertainty is probably the most important thing to keep in mind.

Use Case: Track energy infrastructure investments and policy changes across sectors with AI-powered report generation and automated briefing documents.

Try Runable For FreeKey Takeaways

- AI data centers demand 300-500 megawatts of continuous power per facility, exceeding traditional grid capacity in many regions

- Nuclear energy is getting genuine federal support and private investment, but construction timelines remain 10-15 years for large reactors

- Coal plants are getting emergency extensions while utilities simultaneously plan long-term coal retirement, reflecting market-policy divergence

- Renewables plus battery storage may be more economically and logistically optimal than nuclear in many cases, despite federal promotion

- Grid integration, water availability, and community opposition may be bigger constraints than generation capacity for AI infrastructure expansion

Related Articles

- Why the Electrical Grid Needs Software Now [2025]

- MayimFlow: Preventing Data Center Water Leaks Before They Happen [2025]

- Trump's Offshore Wind Pause Faces Legal Challenge: Data Center Power Demand Crisis [2025]

- LG CLOiD Home Robot: The Future of Household Automation [2025]

- LG's CLOiD Humanoid Robot: The Future of Home Automation [2026]

- Why Data Centers Became the Most Controversial Tech Issue of 2025

![Nuclear Power vs Coal: The AI Energy Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nuclear-power-vs-coal-the-ai-energy-crisis-2025/image-1-1767094570490.jpg)